The restaurant would forever tether Chau, now 24 and a local multimedia artist, to the neighborhood, to the Chinese seafood specialties featured in her artwork, and to the people who have made the Chinatown-International District what it is today.

But after coronavirus-related closures and a surge in anti-Asian racism sent the neighborhood reeling, the idyllic images of Chau’s youth seemed from a faraway past. And then Chau noticed the hateful stickers.

In mid-April, a Chinatown-International District restaurant owner witnessed a group of men with dark sunglasses and face coverings plastering stickers with slogans like “America First” and “Better dead than red” in the neighborhood. The Seattle Police Department’s Bias Crimes Unit is investigating.

“It goes back to the same rhetoric that white folks have used about China and communism and the ‘Chinese virus,’” Chau says, “stigmatizing all of us again.”

Below the slogans, the stickers bore a link to the website for Patriot Front, a white nationalist hate group, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center.

“It made me feel super unsafe,” Chau says. “White supremacists could be literally your neighbor.”

For a while, it was all Chau could think about. She felt deflated and scared and became “really, really worried for a lot of the elders out here.” But then, she says, a sense of responsibility (followed by creativity) kicked in. Inspired by Chinese protective charms, Chau designed a poster with a message for her neighbors in fiery red letters: “Chinatown, Filipinotown, Japantown, Little Saigon were all built on resilience. We will survive this, too.”

“I wanted to counteract these stickers that were so misinformed, so xenophobic,” Chau says, “[and] share that our community has been built on love and on growth and healing.”

Thanks to Chau — and volunteers armed with buckets of wheat paste and staple guns — hundreds of “Resiliency Posters” have appeared all over the neighborhood. The image has traveled the country digitally. Dozens of people have downloaded a PDF version of the poster from Chau’s website, in some cases to be printed and put up in other Chinatowns across the U.S.

While the recent appearance of racist propaganda in her neighborhood inspired her poster project, Chau’s mission to honor the history and vibrancy of Chinatowns is a longer-term project.

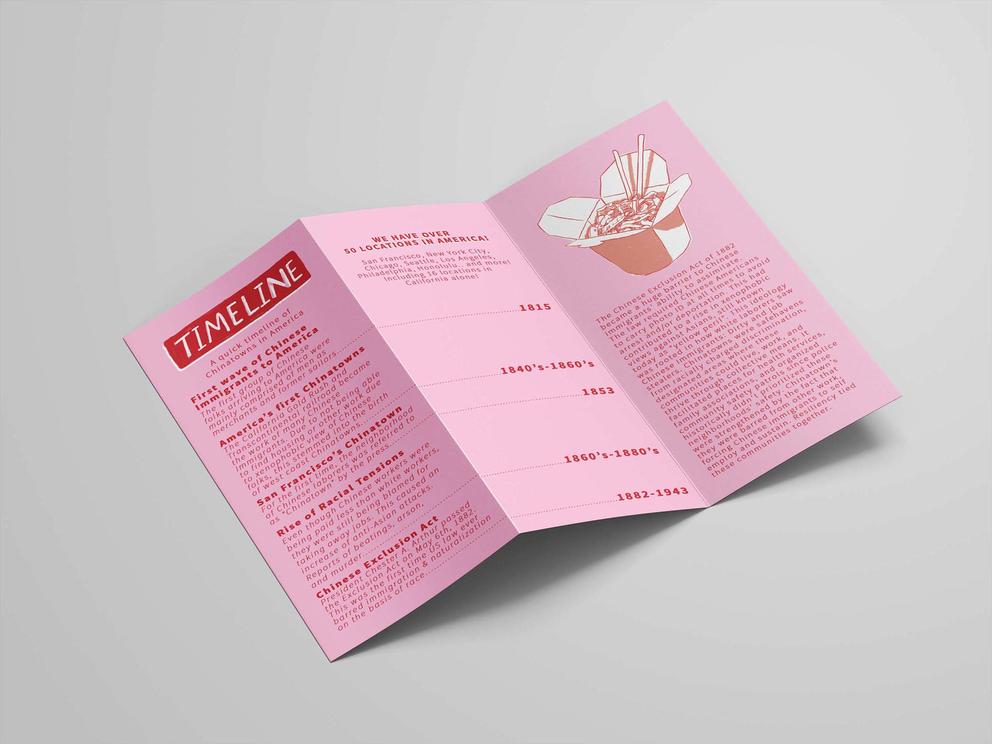

Her recent work includes a brief history of Chinatowns in America (“and the racism that built them”), which she styled as a bright pink takeout menu. “We have over 50 locations in America” the flyer proclaims. “Open: 7 days a week, 365 days a year, even on Christmas and Thanksgiving.”

When she posted a photo of the piece on Twitter in early May, it went viral, with more than 18,000 likes and thousands of retweets. Teachers messaged her to ask if they could use it to talk to their students about the history of Chinatowns. Chau says many people don’t know the neighborhoods arose in the 1800s as the only place Chinese immigrants were able to find housing, community and relative safety from attacks and discrimination in the U.S. (She hopes to visit them all someday as part of an art project.)

“[Chinatown] allowed immigrants to have a place to survive and thrive,” Chau says. “I want to preserve their history. I want to protect them.”

Seattle’s Chinatown-International District isn’t just a memory or concept she wants to protect for others. It’s where her own grandparents made a home and built several businesses after immigrating to the U.S. from Hong Kong in the late 1970s. It’s where she lives, eats, makes art and finds community.

Today, much of Chau’s visual artwork pays homage to her ancestors' food and traditions. On her arm, a shrimp tattoo forever memorializes having grown up, as she puts it, a “restaurant baby.” Right below, the cleaver knife her grandfather cooked with gets an honorary spot, as well as the chicken feet her grandmother “could put away faster than anyone.” Plus, that one phrase of love, “你食咗飯未?,” she heard over and over: “Have you eaten yet?”

In her 2017 installation “A Day's Work of Labor and Love: Xiaolong bao,” which she created at Pilchuck Glass School, trios of ethereal sculpted glass dumplings sit in bamboo steamers like fragile puffs of clouds. The work, Chau says, is a tribute to her ama (grandmother) and cooking as a labor of love and form of communication in families of color.

In Chau's two-dimensional work, Chinese iconography often makes an appearance. Her vitreographs and posters burst with pops of red, and in a zine shown at Bellevue Arts Museum last year, she tells stories of the Chinese zodiac.

This emphasis on her heritage in her work is something Chau’s younger self would have never imagined. She spent most of her youth “ashamed” of her cultural background, she says. In her first years of studying visual art at the Cornish College of the Arts, Chau steered mostly clear of Chinese iconography, or her family’s stories.

Until one day, taking the Metro bus to school, a cluster of sterile, fluorescent lights on a new Bartell drugstore on Jackson Street caught her eye. “I was like: ‘Where … am I? I have no idea.’ And then I realized it was the land that my family's restaurant was on.”

She cried, though it was only later she really understood why: “That restaurant kept me grounded in my heritage and I didn't recognize that until it was gone. Growing up in that restaurant was very conflicting for me, but it really tied me to this neighborhood,” she says.

Since then, she’s been on an artistic mission to acknowledge and appreciate the labor of the immigrants who built the Chinatown-International District, she says. A quest to “protect this neighborhood and give back to it what it has given me.”

With reports of hate crimes and hate speech against Asian Americans increasing amid the COVID-19 pandemic, Chau’s work has found another layer of resonance.

In a new online artwork, “A Comic on Resilience,” Chau channels her feelings about the neighborhood’s current uncertainty. One coral pink panel features a sketch of her grandfather. On the wall behind him, the family logo of a carp. Next to him, yellow font, which reads: “The underlying racism of coronavirus has brought back old ideologies of yellow peril, which in turn threatens the lives and businesses that make Seattle's International District so special.”

“I worry for the sake of this neighborhood, especially because it's in a vulnerable place due to gentrification,” continues Chau’s comic, which she made for a Wing Luke Museum fundraiser (moved online because of the stay-at-home order). “Will we be able to bounce back from this?”

Chau sees some glimmers of hope: families and friends having dinner together over Zoom; the sprouting of a Facebook group called “Support the ID — Community United” to support the mom and pop shops in the neighborhood; total strangers letting her know they’ve donated hundreds of printed posters to her project.

For now, Chau plans to keep plastering the poster all over the neighborhood and sharing it with people across the country. With the help of local community groups, she’s working on a sticker version. And as new white nationalist stickers show up in the neighborhood (and they already have, she says), Chau will add “resiliency stickers” as a counter initiative — right on top of the other stickers.

With every new poster, and every new sticker, Chau wants to give the neighborhood another reminder of solidarity and strength. As she writes in the last panel of her comic: “I remember the resiliency that lives within the streets and the people here. My community keeps me strong, and so does the legacy and stories of all those who came before us. I know we're going to be okay.”

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.