A month and a half ago, Wald, 30, was part of the “nonessential” economy. An artist and illustrator with dual degrees in chemistry (the practical choice) and fine art (her true love), she had left the corporate world to pursue a freelance art career. She was supplementing commissions by working as a server at Capitol Hill establishments Bimbos Cantina and the Cha Cha Lounge. But by early March, as fear of the virus heightened, those normally bustling businesses saw a huge customer drop off.

“It already felt like a ghost town,” Wald recalls, “but we were still all at work.” That’s when she had the idea for a new series of comics that would capture this unsettling time, in the moment. She planned to interview friends, reporter-style, about what it felt like to cook, wait tables and tend bar while rumors swirled about the imminent — and possibly long-term — closure of restaurants. “I wanted to cover that eerie feeling,” she says.

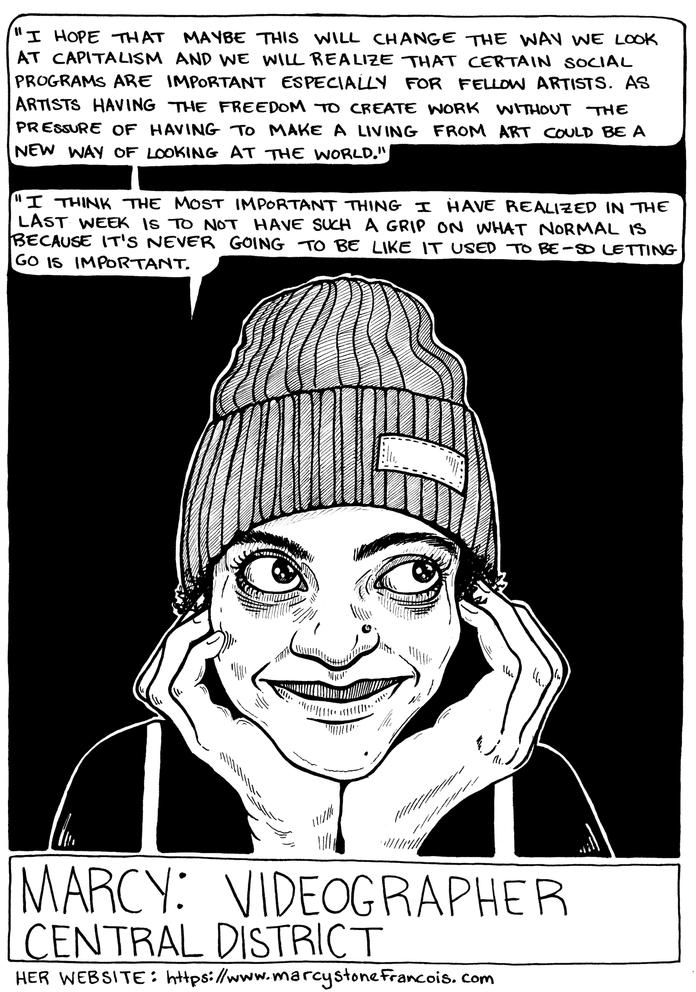

It wouldn’t be Wald’s first comic series based in real life. Last year, she received a grant from Artist Trust to complete a comic book called The Golem: A Family History, inspired by memories of growing up in Buffalo, New York, family lore and the Jewish diaspora. In all of her work, Wald creates a striking black-and-white contrast — sometimes featuring compressed cityscapes with buildings jostling together, sometimes with pitch-black backgrounds that make her portraits pop. She pays particular, expressive attention to eyebrows.

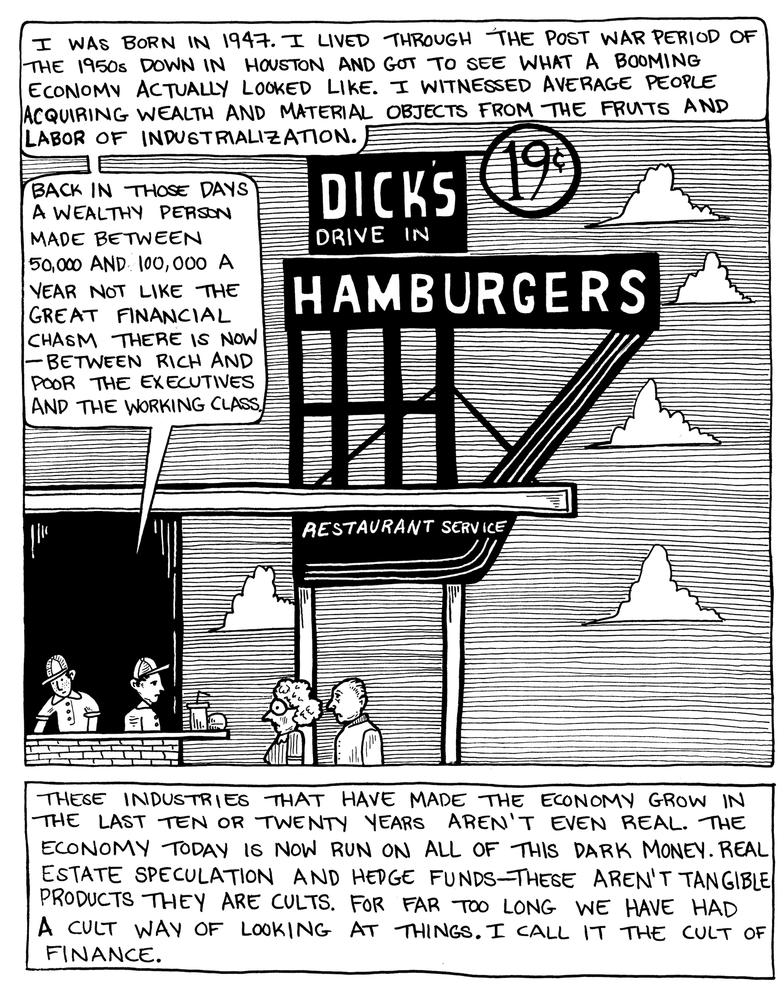

A few days before Gov. Jay Inslee issued his restaurant closure mandate (“which happened on the ides of March!” she says, noting the ominous legacy), Wald gathered stories even as customers grew more sparse. In the first few comics, her subjects are still at work, but without much to do.

“They say ‘idle hands do the devil’s work,’ ” says Ava, a line cook in South Lake Union. (Wald changed some of the names in the comics for privacy.) “We have thrown ourselves into improving sanitation,” Ava continues, “but every day it feels more like it’s the only job we have left.” Tavio, a prep cook in Pike Place Market/Westlake, remarks, “The fear of losing your job is way greater than the fear of losing your toilet paper.”

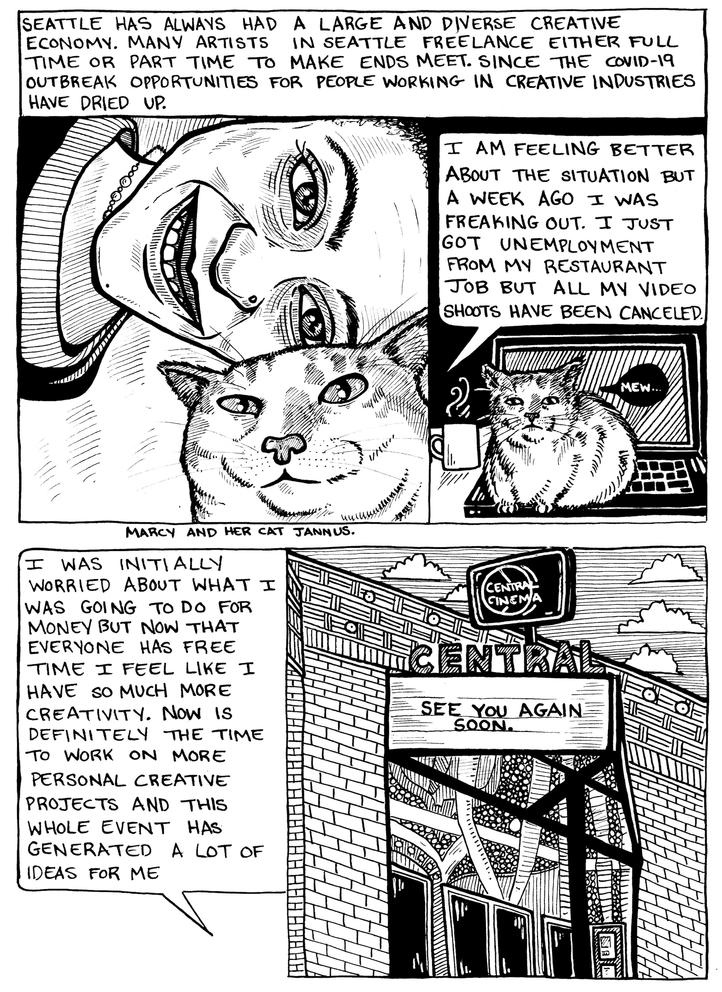

Wald soon realized she wanted to capture a wider range of stories from a diverse group of workers. “I wanted to cover what people are going through,” she explains, “which is why I needed more perspectives.” On March 12, she posted a call on Facebook: “Are you a healthcare worker/teacher/public servant/restaurant employee in King County? Would you be interested in talking about how COVID-19 has affected your work, business, health and/or income?” She started getting responses, and began interviewing and illustrating people she didn’t know.

“I was really inspired by the book Working, by Studs Terkel,” Wald says. Published in 1984, the book is a collection of oral history interviews conducted by the renowned author and radio broadcaster. (Comics legend Harvey Pekar did an illustrated version in 2009, she notes.) In the book, Terkel emphasizes the essential task of documenting workaday life. “Studs liked capturing the mundane, the everyday,” Wald says. “In a strange way I feel as if I am capturing the mundane — except it’s in a pandemic. I’m interviewing people about their day-to-day emotional responses and lives — normal stuff — in an extraordinary time.”

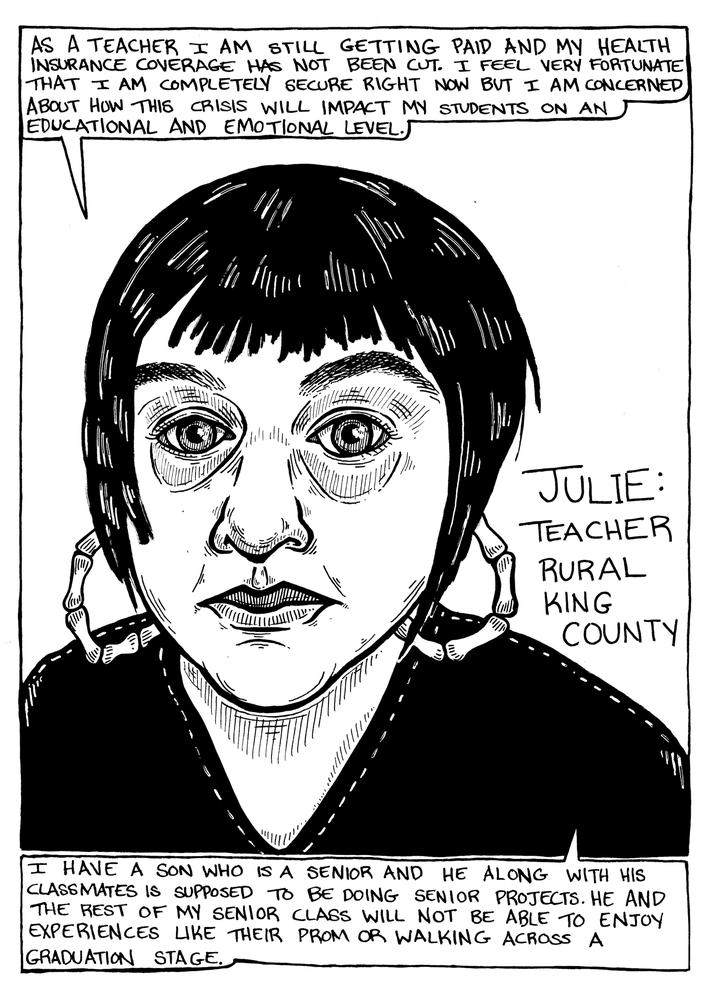

“We have students who receive free- or reduced-price lunches,” says Julie, a teacher in rural King County. Wald illustrated her words in all-caps on a school lunch tray with a carton of milk, broccoli, a cookie. “So our administration has made an effort to deliver lunches…. Other students that I know of are stuck at home with violent family situations and there is no escape.”

Jayne, a health care worker in South Seattle, talks about how the pandemic has affected her position as an on-call neurospecialist in acute care hospitals and outpatient therapy. “Hospitals are overburdened with COVID-19 patients,” she says, “and they are starting to turn away people with conditions that are considered less severe — like my patients.”

In the illustrations, Julie looks pensive, Jayne, friendly and trying to stay positive. “When you’re drawing someone, you always have a lump in your stomach,” Wald says. “Am I getting it right? Will they think it’s unflattering?” For the interviews she conducts over the phone (others are at a social distance), she works from the photographs her subjects send her. She uses India ink pens for the black lines, and white gel pens (“they changed my life!”) for cleanup and details, such as strands of hair. Her boyfriend, a chef at a tech company, helps condense the interview text to a few panels.

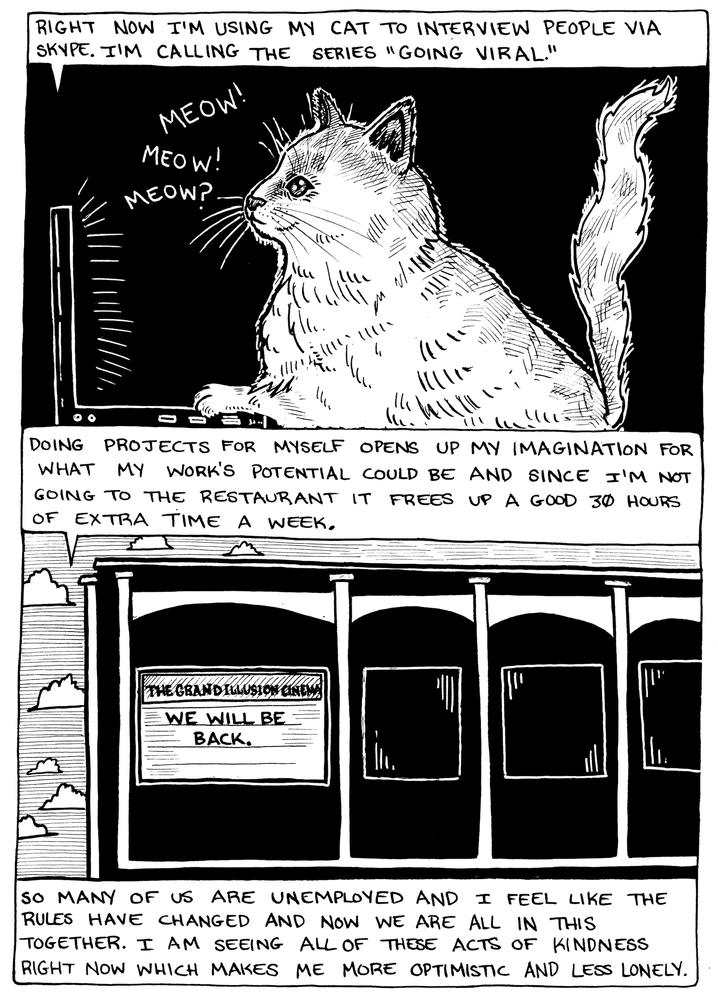

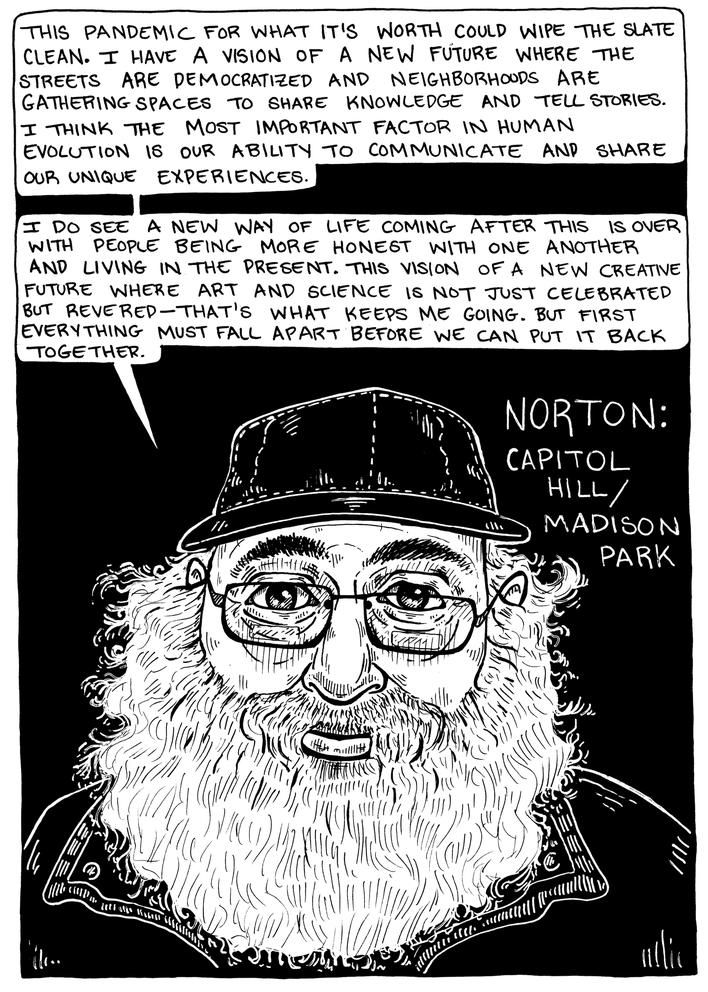

Wald captures people in various states of job insecurity — a graffiti artist, a homeless shelter worker, a musician, a freelance videographer. One of the comics features Norton, a 73-year-old man who has been living homeless for the past 25 years. “He’s a neighborhood fixture on Capitol Hill,” Wald explains. While she doesn’t know much of Norton’s background, she does believe he’s had an education. “The last time we talked,” she says, “he was quoting from Sun Tzu’s The Art of War [the ancient Chinese military treatise].”

In Wald’s drawing, Norton has an expansive Santa beard, spectacles and kind eyes. “I did notice a shock set in on the streets after the restaurants closed,” Norton says. “There are no leftovers for the homeless people to eat…. I can see a desperation in the community that was not there before.”

When the pandemic first hit, Wald wasn’t sure what would happen to her illustration career, which had just begun taking off. “At first, the sudden change was extremely discouraging,” she says. “I had some major illustration projects that were put on hold indefinitely. I felt like I was mourning my creative past a bit.” But with an uncertain financial future, she felt lucky to land her new “essential” job at the startup. (The chemistry degree helped.)

And although the work doesn’t allow her much free time, she is driven to continue her pandemic comics, and eager to interview more people. She’s already planning to speak with a grocery store employee, an arts organization leader, a bus driver. (Follow the expanding project on her Instagram page.) In so doing, she is documenting the everyday upheaval of this moment in history, as it unspools in real time.

“I have no idea what my end goal is,” Wald says. “It just needs to come out. I’ve always been like that,” she says of her creative work. “It’s a physical response, like eating when you’re hungry, like drinking water.” In other words, it’s essential.

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.