The opportunity came courtesy of a retro-style online video game called They Want Us Dead, the brainchild of local blues/punk band The Black Tones (who, by the way, contributed an awesome cover of Jimi Hendrix’s “All Along the Watchtower” to the star-studded All In Washington COVID-19 relief concert Wednesday night).

The brother-sister duo leading the band, Eva and Cedric Walker (who are twins), came up with the video game two years ago as an accompaniment to their song “The Key of Black (They Want Us Dead).” In a 2018 interview with AfroPunk, the Walkers explain that the song is “about these people who want us dead simply because of us being who we are, Black.”

The game looks like an old-school 8-bit video (the twins say they were fans of Super Mario World and Donkey Kong Country growing up), with two-dimensional right and left scrolling action, and jumping and crouching controlled by arrow keys (all courtesy of developers David Brender and Corey Kahler). You can choose to play as Eva or Cedric. I went with Eva for the chance to wear her signature white go-go boots.

In a recent interview, Eva told me the game has experienced a rush of new users since the protests against racial injustice started. “A lot of people had no idea we released this,” she says. “They probably need it now in a way they maybe didn’t before.”

While it’s based in the very unfunny truth that racism is lurking around every corner, They Want Us Dead is also kind of hilarious — thanks in part to the pixelated graphics and swingin’ 8-bit soundtrack. But Eva points out something else. “I think humor gives the perspective of how ridiculous these people sound and look,” she says. (The game also includes quotes from each hate group: “We are just celebrating our own heritage!” “Make America White Again!”)

It’s also surprisingly satisfying to knock out a cartoonish neo-Nazi. “Catharsis can lead to a renewed sense of strength, which can lead to more resistance,” Eva says. “It takes a lot of energy to fight a system built to harm you. So we need breaks, fun, love, music. Games. Then we go back, refilled.”

For me, experiencing and thinking about art is a refiller, a recharge.

I was recently buoyed by a Facebook update from longtime Seattle artist Barbara Earl Thomas, who posted about her creative process during the pandemic. She’s currently at work on a new show of intricate cut paper and glass pieces, The Geography of Innocence, set to open at the Seattle Art Museum in November (the coronavirus willing). I was captivated by the short video that showed Thomas carefully slicing slender shapes from a large sheet of black paper, revealing human figures and fiery colors smoldering beneath the cuts.

She has been creating this body of work over the past two years, so I asked what it means to her in the current moment of protest and pandemic. Thomas said self-isolation has had her feeling “alternately helpless and detached, as if watching the world from a terrarium … a dome of silence.” But with the racist incident involving birder Christian Cooper and the killing of George Floyd, “the silence was shattered.”

I asked her about the piece that depicts a young person looking off to the side, holding a simple sign that says, “Grace” (also the name of the work). Thomas told me she created the piece after seeing photos of children holding signs reading, “Don’t shoot.” The photos prompted her to ask herself, “What is it I want?” The answer, she says, was both desire and prayer: “Before you pull the trigger, I want grace — a moment of hesitation, a moment of thought, a chance to change the story’s ending. In that moment is where grace resides. It’s grace for the shooter and the one who is shot — two lives saved.”

Protest art helps us visualize change as possible. And the art with the greatest impact frequently exists outside the gallery space — accessible to everyone. Sometimes it’s in direct rebuttal of the gallery space, such as this week’s mysterious fake press release, written to look as if it came from the Seattle Art Museum, announcing that the museum would be dissolving by 2022 and distributing all its assets to “a trust governed by a coalition of local BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and people of color) art organizations.” (SAM acknowledged it as a “well-done piece of satire.”) Text at the bottom of the document stated “This is a work of speculative fiction,” but the hoax raised real criticisms of the systemic inequities at many mainstream museums.

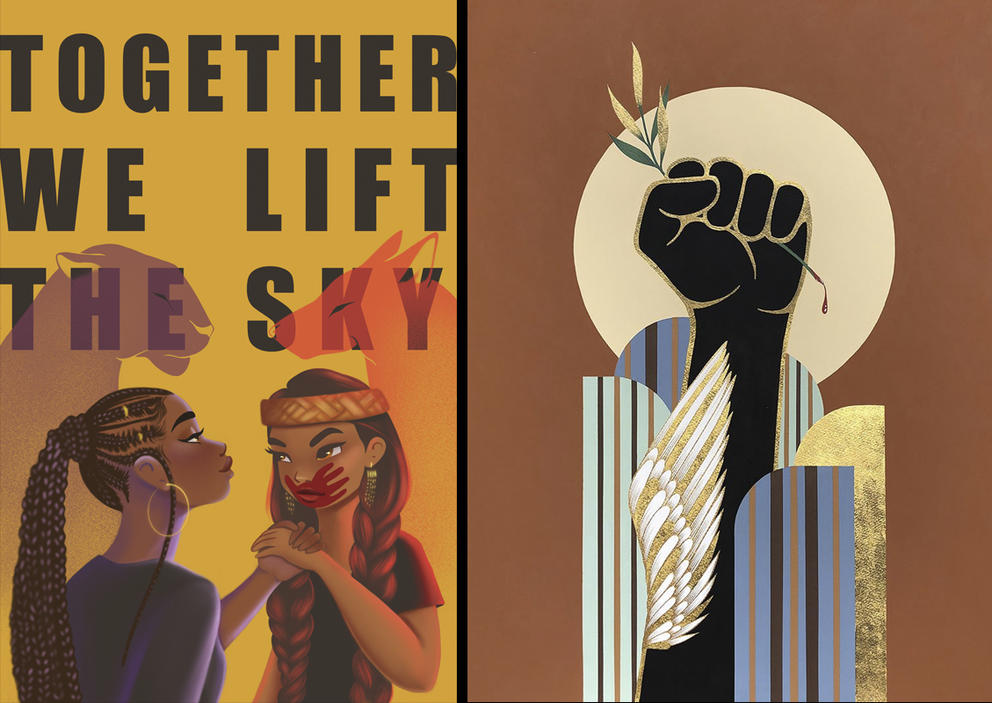

There’s been an abundance of activist art in recent weeks, including murals, comics and posters — such as those by Seattle artist Michelle Robinson (who goes by Mister Michelle) and Tacoma artist Paige Pettibon (a member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes). The former created a Black power fist and gave it a gold encrusted wing to fly higher; the latter illustrated a promise of solidarity among Indigenous and Black people fighting injustice.

Such art isn’t just beautiful, it adds momentum to societal progress. Just consider how the powerful imagery of the rainbow flag, Keith Haring’s artwork and the AIDS Memorial Quilt became emblematic in the struggle for gay rights. The LGBTQ community has made huge strides in the last decades, including last week’s Supreme Court decision confirming workplace protections for gay, bisexual and transgender employees.

While Pride festivities were canceled because of the coronavirus pandemic this year, we can celebrate those wins — and commit to continued progress — with a packed three-day schedule of virtual events called Together for Pride (June 26-28, free with registration).

Some art that erupts during social upheaval is momentary, some persists in minds and hearts, whether a poster, a painting, a flag, a fist or maybe even a video game.

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.