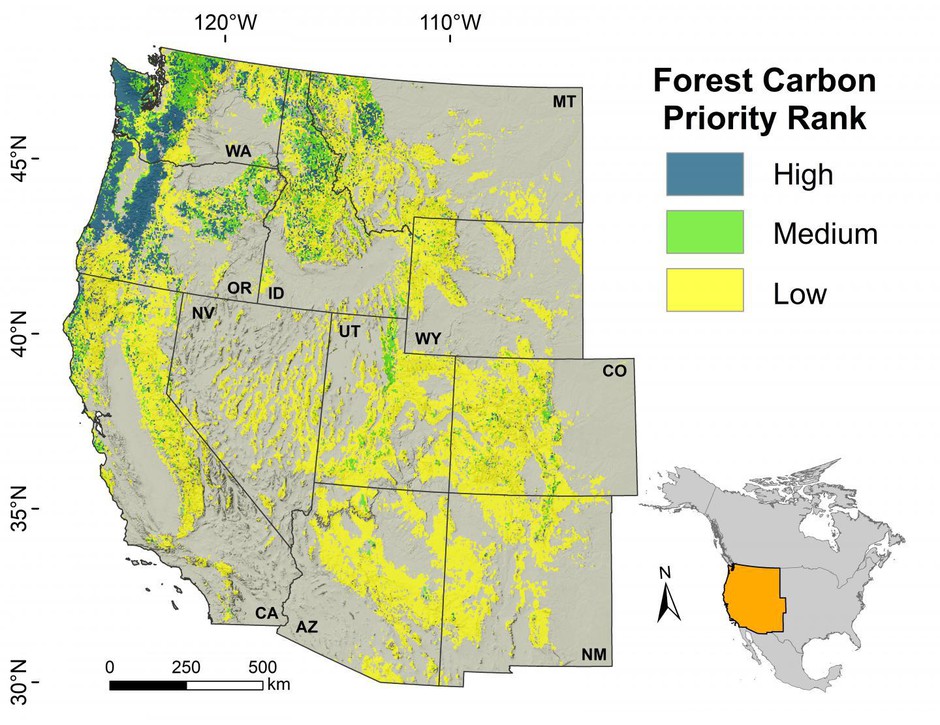

They analyzed which forests have the most potential to sequester carbon, are least vulnerable to drought and fire, and also provide valuable habitat for endangered species.

Many of the forests that hit that trifecta are along the Oregon and Washington coast and in the Cascade and Olympic mountains.

“The amount of carbon per acre that they take up is as high or higher than tropical forests,” said Beverly Law, a professor of global change biology and terrestrial system sciences at Oregon State University and co-author of the study. “Those are really what I call the land sinks that are so critical to try and make sure we preserve them.”

The study, published Dec. 4 in the journal Ecological Applications, finds that not logging high-value forests would be equivalent to halting six to eight years of the region’s fossil fuel emissions.

“To some, it might seem like a sacrifice,” Law said. “To others, it might be, ‘Thank goodness, I can do something to help us get out of this problem we’ve gotten ourselves into.’ It is serious.”

Burning fossil fuels like coal, gasoline and natural gas produces carbon that gets trapped in the atmosphere. This is resulting in rising average temperatures and many dire consequences: melting glaciers, extended droughts and more severe wildfires, among them.

The study found the high-value forests make up about 10% of the forest land in the West, including some areas in northern Idaho and Montana.

The Oregon Forest Industries Council did not respond to a request for comment. The industry group has criticized Law’s previous research findings that concluded timber harvest is the leading source of carbon emissions in Oregon.