But Wallace is full of energy. He tells each person his well-rehearsed spiel: A company is trying to build the world's largest fracked-gas-to-methanol facility just 30 miles north of here in the Washington town of Kalama. He's running for commissioner of the Port of Kalama in the November election and wants to stop the project. Here's a flyer with some information. If you want to learn more, there's a booth just over there. Look for the red "No Methanol" sign. Then he moves on to the next person.

Early that morning, Wallace and a half-dozen other activists made the 40-minute drive down from Kalama, a town of about 2,700 in Cowlitz County, to this gravel lot. They're part of a small band of grassroots activists who came to get the word out about their three-year effort to stop construction of the $2 billion methanol plant project proposed a few miles north of Kalama.

The company behind the project, Northwest Innovation Works (NWIW), has connections to the Chinese government through its parent company, the investment arm of Chinese Academy of Sciences. NWIW is awaiting for approval from the Washington state Department of Ecology for an environmental permit to begin construction. A final decision from the agency is not expected until at least December. Until then, members of the Kalama-based activist group No Methanol will spread its message to whoever listens.

Back in Kalama, opinion about the methanol plant is starkly divided, creating tensions in a town one local referred to as “Mayberry.” Wallace built his campaign for port commissioner almost entirely on opposing the methanol plant, but his opponent, incumbent Port Commissioner Alan Basso, easily won reelection on Nov. 5. His landslide victory points to public support for the port’s plan to go ahead with the plant.

But public opinion won’t determine the project’s outcome. That will likely turn on the approval of required environmental permits by the Washington State Department of Ecology, which is expected to make a decision before the end of the year. And a newly announced lawsuit by environmental groups is challenging previously issued federal permits, adding another obstacle that NWIW must overcome before construction can begin. With the uncertainty around the permitting process and associated legal challenges, the outcome of the methanol plant is as murky as when it was first announced in 2014.

A clear and colorless liquid

Methanol is a clear and colorless chemical that is liquid at room temperature. It has a wide variety of commercial applications, from industrial solvents to fuels to use as a feedstock for plastics, fabrics, cosmetics and more. But NWIW looked to the Northwest for reasons of access to the methanol’s source and its ultimate destination: Abundant natural gas extracted from fields in Western Canada and the United States would be piped into the Kalama plant, where it would be converted into methanol and shipped to Asia. As much as 3.6 millions tons of methanol could be produced at the plant each year, making it the largest of its kind in the world.

In its most recent decision about the permits, the Department of Ecology in mid-October held that the Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement submitted by the company and Cowlitz County in August was incomplete. The agency requested additional information from NWIW about the project's atmospheric carbon impact and mitigation plan, among other issues. Both parties responded in early November and the Department of Ecology is expected to issue another decision by December.

The methanol plant would sit on a 90-acre site on the northern end of Port of Kalama property, which sits on the banks of the Columbia River and is home to a public park and more than 30 businesses — including a marina, a restaurant and a steel-processing facility.

Port Commissioner Basso supports the methanol plant. At a town hall in Kalama on Oct. 21, Basso argued that the project is an excellent fit.

"What we do [at the port] is we focus on putting in infrastructure that allows outside money to come in and build businesses, put people to work, pay taxes, and these tax dollars go to the other local entities," Basso said. "There's a group that wants to make this all about methanol, but the port does a lot more than methanol."

Wallace, who is also the president of nonprofit environmental group Lower Columbia Stewardship Community, had a stark rebuttal.

"Fossil fuels are not the wave of the future," he said. He'd like to increase transparency of the port’s decision-making process and have it focus on light industrial and recreational uses, such as a graffiti park that could host competitions for artists.

”I’m not telling people ‘here’s what you need’ — If you don’t think we’re on the right path, then get involved and bring your ideas and get creative,” Wallace said.

An economic boon?

First proposed in 2014 alongside two similar facilities in Tacoma and Columbia County, Oregon, the Kalama plant is promoted by NWIW as an opportunity to bring jobs and investment to Cowlitz County, which has an unemployment rate nearly 1.4% higher than the state average. Still hurting from the 40-year decline of the timber industry that once sustained it, many in Cowlitz County hope the plant can bring the good times back.

In addition to Basso and the two other port commissioners, the project is supported by state Rep. Richard DeBolt, R-Chehalis, and former Washington Gov. Gary Locke, both of whom have taken paid positions with NWIW or its parent company. Gov. Jay Inslee was also a supporter of the project until he reversed course last spring around the time he announced a climate-focused presidential campaign.

NWIW selected Longview-based contractor JH Kelly to build the facility, and expects to hire 1,000 workers during the two-year-long peak construction period. To that end, the company signed a labor agreement with local construction trade unions at the outset of the project.

“I and other local union members are excited to be a part of this project,” said Mike Bridges, president of the Longview/Kelso Building and Construction Trades Council and a member of IBEW Local 48. He sees the methanol plant as a way for local unions to diversify, and believes high environmental standards will prevent possible pollution impacts.

Once operational, the plant will require 190 to 200 permanent employees with average salaries of $109,000, NWIW said. The company is also funding a training and internship program with Lower Columbia College in nearby Longview to help local residents fill at least 20% of the permanent jobs at the plant. The program will also focus on creating a job pipeline for local adults and young people.

NWIW donated $10,000 to the Kalama library for renovations, and promised the local fire district $1 million if the plant is approved by the state. Eric Nerison, superintendent of the Kalama School District, told Crosscut that NWIW had committed to donate $25,000 in cash and $25,000 in in-kind services for teaching and training as part of its grant application to the state of Washington. NWIW confirmed that the company had made financial commitments to the school district, though it didn't specify an amount.

Rosemary Siipola, a long-time resident who ran for mayor of Kalama in 2017 and is a board member of the Lower Columbia College Foundation, said the project would bring much-needed money and jobs.

"The port's core values are to do the best it can for the community it serves — I don’t believe that they would be supporting this effort if they didn’t believe it was viable and a good fit," Siipola said.

"Government oversight of of this project has been incredible, so if the state approves the permits, I'm OK with the plant being built," said Steve Kallio, who defeated No Methanol member John Flynn for a city council position on Nov. 5. “I think the people have spoken about that issue and I hope we can move forward with issues that actually are controllable by the city.”

“I’m glad there are environmental groups who are involved, but I think they should focus on their own area and not tell people in Kalama what to do.”

Opponents remain unconvinced

The clearest sign of opposition to the plant can be seen on a small building in downtown Kalama with a 5-foot-long red banner that reads, "NO Methanol Refinery" hanging above the door. The storefront, currently unoccupied, has previously been a gym, video store and an antique store and is owned by Diana Leigh, a longtime Kalama resident. She has let the No Methanol group use it for monthly meetings since 2017.

"I personally know many people who are against this project, but are afraid to take a stance for fear of losing their jobs, homes or friends," Leigh said.

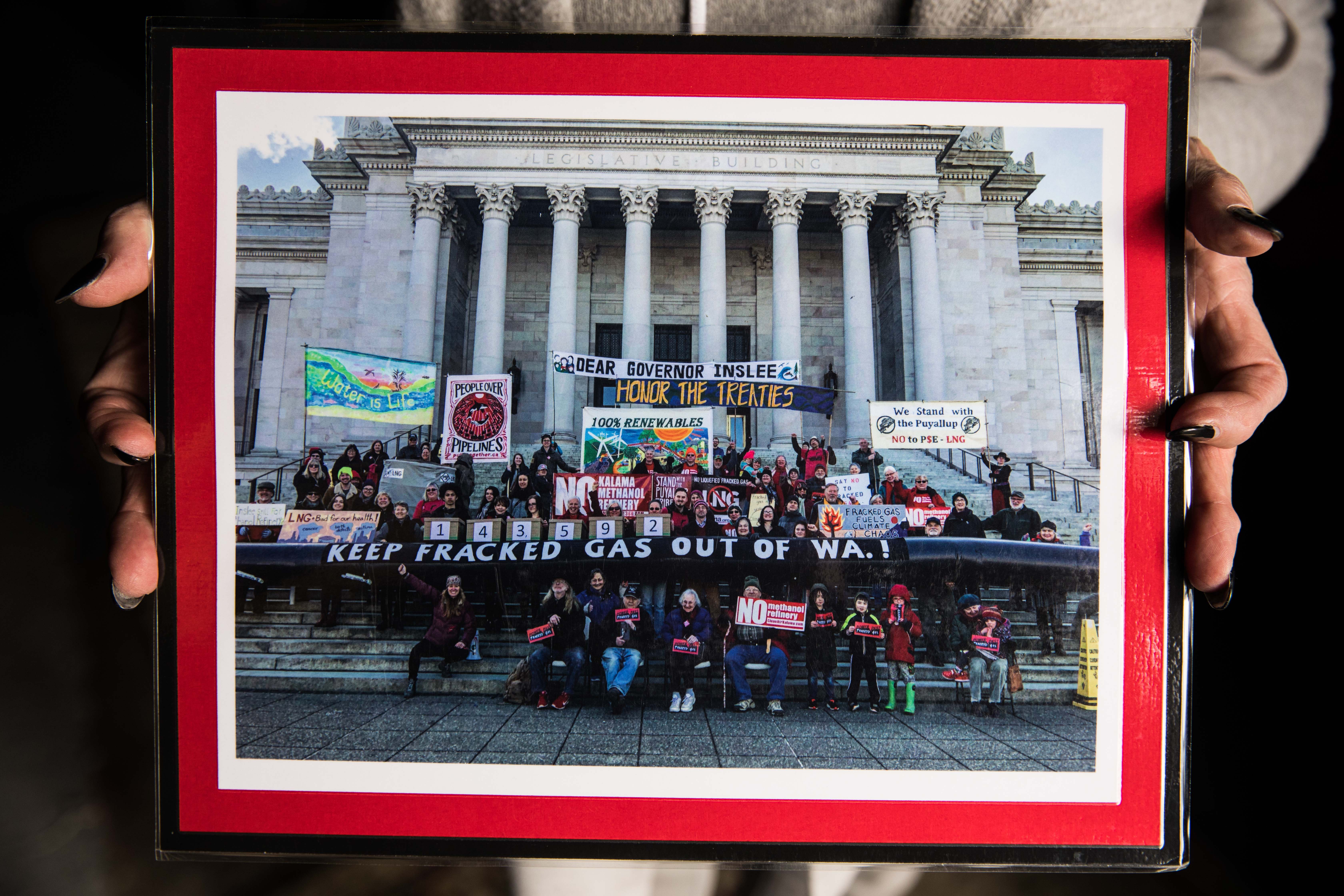

Founded in the spring of 2016, No Methanol plans actions like attending public meetings, writing letters to state agencies, waving signs around town and setting up informational booths at public events. Group members have driven to Department of Ecology headquarters in Lacey for protests several times in the past few months. A team of volunteers researches issues of concern, including health impacts from chemicals and NWIW visa requests, posting the results on two websites. The group also coordinates closely with local environmental groups like Columbia Riverkeeper and the Sierra Club.

Linda Horst, from nearby Kelso, worries about the methanol plant's possible health and safety risks, and its use of 5 million gallons of water per day from local sources.

"China gets the product; we get the pollution,” Horst said.

No Methanol’s John Flynn is concerned about the effect the plant's lighting would have on the wild salmon running up the Kalama River. He also questions how many locals would actually be hired for permanent jobs, noting that the company's definition of “local” includes a 12-county region surrounding Kalama. Flynn also points to public records that show the company has applied for four H-1B visas — work permits for foreign nationals.

Climate change worries

Opponents of the plant also worry about its greenhouse gas emissions and climate impact. NWIW said the plant operation would result in an estimated net global reduction of 12 to 15 million metric tons of carbon dioxide per year. Part of this reduction is based on the company’s commitment that all methanol from the plant would go toward plastic and material production and not used for fuel. The company has also committed to mitigating all emissions associated with the project in Washington state — even those not directly tied to operations.

The analysis supporting the greenhouse gas emission reduction claim is laid out in several environmental impact statements the company filed with the state. It relies on complex scientific and economic assumptions that predict the Kalama plant would displace dirtier production facilities overseas that produce chemicals equivalent to methanol. Those alternative production pathways, some of which use coal, would produce higher levels of greenhouse gas emissions than NWIW’s natural gas-to-methanol process. The company has also applied for a $2 billion loan from a U.S. Department of Energy program meant for companies that use innovative technology to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Not everyone agrees with the company's analysis, however. Peter Erickson, a senior scientist at the Stockholm Environment Institute, a nonprofit research and policy organization, questions NWIW's claims about the project's impact on climate change.

“It’s not plausible that to say that this facility is going to lead to greenhouse gas emission reductions on the scale that Northwest Innovation Works claims," Erickson said, adding that there's no evidence the plant is going to displace coal-based methods of plastic production one-for-one. Further, because the plant would result in more methanol on the market, Erickson said, its operation could lead to greater consumption of methanol and higher overall greenhouse gas emissions than the company predicts.

Methanol as fuel?

Kent Caputo, NWIW’s chief commercial officer and general counsel, told Crosscut that the company would ensure that all the methanol from the Kalama plant would be used only for plastic materials production once shipped abroad, and that enforceable regulatory safeguards and contractual commitments are in place that will constrain project methanol to a materials pathway.

Caputo said the company hopes to set new environmental standards for methanol and plastic production. He sees a future where consumers will to know the source of the plastic in the products they buy, as bluesign technologies has done for textile products.

“Looking ahead, we believe there will be fewer single-use plastics and that consumers will want to buy products which use materials from responsible producers like NWIW,” Caputo said.

But the claim that methanol would be used only for materials was challenged this past April. Documents made public by Oregon Public Broadcasting showed that third parties connected to NWIW told investors that methanol from the plant could also be sold as fuel overseas. Caputo told Crosscut that the documents were accurate and authorized for use, but stood by the company’s claims that all methanol from the plant would only be used for materials.

Dan Serres, conservation director at Columbia Riverkeeper, points to the report in raising questions about the methanol’s end use and says NWIW is engaged in a "deliberate misinformation campaign."

“There’s a conflict between public statements and investor communications from NWIW,” he says.

After the documents became public, NWIW amended its dock use agreement with the Port of Kalama in a way that would prohibit the company from selling the methanol produced at the plant for use as fuel. If found in breach, the company would face financial penalties and be required to supply the port with shipping and sales records.

Basso, the port commissioner, said tracking methanol once it has left Kalama is feasible.

"You can track any shipment of anything across the ocean — there are even little apps on your cellphone where you can do that,” Basso said. “They [NWIW] are not going to blow this. They’re not going to take this opportunity and waste it."

An economic counterargument

Beyond the environmental concerns, several local elected officials argue that the Kalama plant could instead have unforeseen deleterious effects on the local economy.

Kalama Mayor Mike Reuter is a tall, broad-shouldered man who identifies as Republican and doesn't consider himself an environmental activist. But Reuter is against the project because he believes that the plant's creation would facilitate the flow of natural gas — a strategic natural resource in his view — from North America to China. The plant would consume 320 million cubic feet of natural gas daily, and on an annual basis would use more natural gas than all the region's biggest cities combined, according to the Sightline Institute.

"The additional competition from the Asian markets would greatly increase regional gas prices and cause Northwest energy security issues, especially during the winter months," Reuter said. "You don't give your greatest competitor an advantage like that."

David Taylor, a natural gas engineer and city councilor in nearby Ridgefield, Clark County, also argued in an op-ed in Vancouver, Washington's The Reflector that the plant would require an infrastructure expansion of the Williams Northwest Pipeline — the sole source of natural gas from Canada for Washington and Oregon — that could cost several hundred million dollars. He believes all users of the pipeline, including household customers, would end up paying for it.

NWIW’s Caputo said the company does not foresee the need for pipeline expansion. He also said that more capacity would be available in the future in part because of a law passed in Olympia last May that mandates all of the state’s utilities to use 100 percent renewable energy sources by 2045. According to Caputo, the new regulations over time will reduce the number of natural gas power plants in the state and free up pipeline capacity.

Mixed feelings from neighbors

A stone's throw from I-5 and bordered on two sides by the Kalama River, Camp Kalama is a private campground about a mile away from the proposed plant site. The business has been in Charlene DesRosier’s family since the ’80s. Her nearby home uses well water, and she wonders whether she'd still be able to eat from the fruit trees that grow on her property if the plant is built. NWIW said the plant will use 5 million gallons of water daily, drawn from the local aquifer.

“A methanol plant is not going to attract new families or people to this region," she said.

The Kalama Sportsman’s Club is another campground located on a scenic spot, at the junction of the Kalama and Columbia rivers. Vern Eaton, president of the Sportsmen’s Club, said the organization doesn't take a position on the methanol plant. While acknowledging that some members are against it, he remains unconcerned. "We're not worried about pollution,” he said. “No water will be put in the river, and any water used by the facility will come out of the aquifer and go back into it."

Local concern extends to the Oregon side of the Columbia River. Karlyn Gedrose and Greg Hoffman live in Prescott, Oregon, on 4.5 acres of riverfront property directly across the proposed plant site. Should they choose to leave, they worry that the pollution and aesthetic impacts could drive away potential buyers. In addition to their personal financial interest in stopping the plant from being built, Gedrose said environmental impacts on fish and wildlife also play into her opposition.

“It doesn’t add up, even if you take our personal interest out of it," she said.

In the near term, the plant’s fate is uncertain — likely for months, even years. In early November, NWIW and Cowlitz County responded to the Department of Ecology's request for more information on greenhouse gas emissions and related mitigation plans.

In September, Columbia Riverkeeper and the Center for Biological Diversity filed an appeal of a previous decision from the Washington State Shorelines Hearing Board regarding the permits. Rick Desimone, a consultant for NWIW, confirmed the company is engaged in that litigation. Columbia Riverkeeper is also part of the new lawsuit filed on November 12th that is challenging multiple federal environmental permits previously granted to the project.

Opponents of the plant say they will continue fighting. No Methanol is planning to protest again at the Department of Ecology’s headquarters in the coming weeks. Despite his loss in the port commissioner race, Wallace said he wasn’t giving up.

"I’m going to definitely stay involved with the port,” he said. “Even though I lost, I think I opened up some ears and eyes and shook up the tree a little bit."