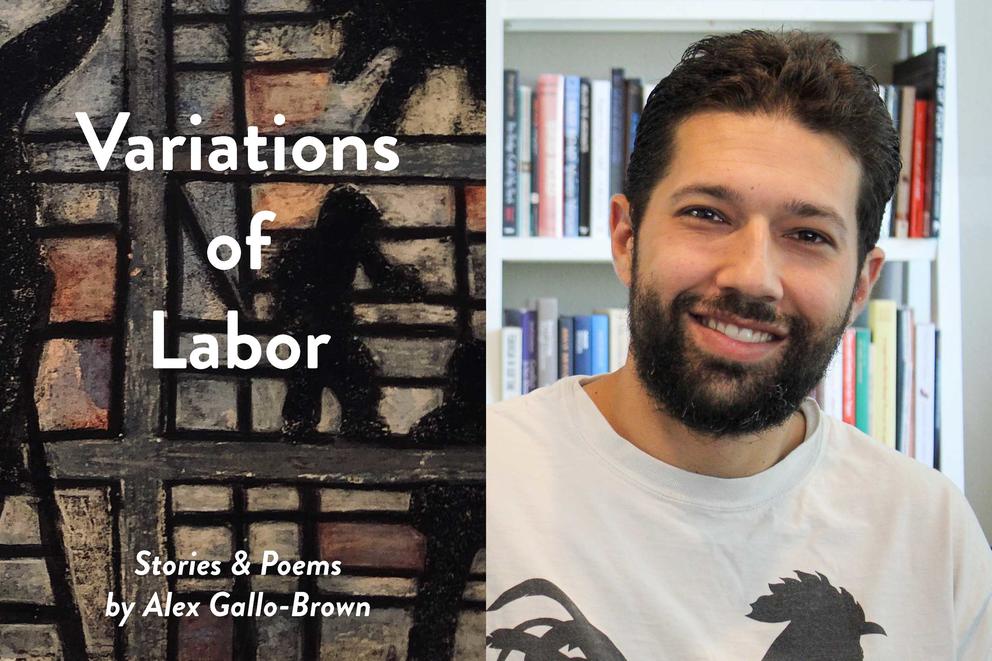

The sickness of a family friend and suicide of a co-worker had left him grieving. He felt empty. But writing made sense. One day, when he didn’t bring his notebook, he asked the barista for a paper bag to write on. The lines he jotted down on the brown paper eventually grew into the epic poem “In Starbucks on My Thirty,” one of the anchors in his new book, Variations of Labor. The collection of poetry and short fiction is set to be released Oct. 1 by Seattle publisher Chin Music Press. (Gallo-Brown will read from his work on Labor Day at Town Hall.)

The book is, in a way, also a homecoming. Gallo-Brown, 34, grew up in Seattle but wrote most of his first self-published book of poetry, The Language of Grief (2012), while in Portland and New York, grappling with the death of his father. Variations of Labor, meanwhile, is a love letter to his now-changed hometown: the busy arterials, strip clubs, cafés and eateries of its past and the hold-outs of its present.

In one blistering poem, an unnamed narrator shares garlic prawns with a “North Seattle NIMBY” at a Thai restaurant on Eastlake. In the short story “The Morning Tournament,” a young man finds solace in the feta cheese omelet at Roosevelt’s Sunlight Café — even though it costs him about half of the money he just won in a poker tournament (and about the same amount he makes working a couple of hours at his community center job).

In many of these stories, Gallo-Brown culls from his personal experience, particularly his long string of service work gigs and the people he has met through his job as a union organizer. His words are dedicated to the grind, the daily diligence, the people in scrubs, the truck drivers, the pizza deliverers, the cooks, the women dancing in strip clubs — and Gallo-Brown’s uncle, who worked as a landscaper, construction and maintenance worker.

“He died penniless at 60,” Gallo-Brown said. “I think [he’s] an example of a type of very warm, expansive human being that this system chews up and spits out. The book is dedicated to him, and people like him.”

Crosscut spoke with Gallo-Brown about expanding the definition of labor, about toxic masculinity and whether art is a luxury in the face of struggle.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

The title of the book comes from a childbirth class you attended with your pregnant wife, where you learn about “labor and the variations of discomfort.” How is this kind of labor connected?

I like the idea of expanding the definition of labor to encompass all of the work that we do as human beings as we try to be the best versions of ourselves. And that's not just what you get paid for; it's also all the stuff you're doing in your private and communal life. For me, it also has a political content because I think so much of our governing ideology is around this idea … that hard work is good. I am arguing somewhat implicitly in this book that there are many forms of labor, and if the market assigns you very little value [because] you’re working a job where you don't make very much money, that doesn't mean that you don't have a lot of value as a human being. You're still a person who grieves and feels and experiences.

How do you see the book’s release in the broader context of current discussions around labor?

There is definitely a surge right now of thinking about labor, which I think is a great thing. I've seen opinion polls about unions for example, and somewhere between 60% and 70% of people, especially younger people, feel positively about unions. I think [we’re] going to see more and more labor agitation, searching for [ways] to improve working conditions.

How does your book, and poetry in general, fit into that picture?

I think literature and poetry and perhaps my book can help illuminate certain issues. Especially the conditions, the experience of being a low-wage worker right now in 2019. What does that feel like? I don't think low-wage workers get much of a voice in the culture. Most of the culture people are consuming is being created by people who [are] probably on the other side of things.

As far as what a poem does politically, I don’t know. If it does anything, if it's succeeding, it's making people feel more in touch with their own humanity and perhaps gives them a greater sense of empathy and compassion for other people. I hope that through the writing, people who don't have as much experience with low-wage work maybe get a window into [it], and people who do see themselves in it and don't feel so alone.

In your short fiction, characters grapple with the idea that making art is a luxury. In one story, a writer struggles to answer a question he gets asked about his book-in-progress: “What’s the point of writing it?” What is your own answer?

It's been a tension in my own life since I became politically active in my early 20s. Some of it is: How do you spend your time? Is my time [best] spent as an activist, organizer, or is it best spent carving out this time for myself to try to explore ideas and write poems and think in a clear way? And then, of course, as a low-wage worker struggling economically, you don't have a lot of time to make art. You're hustling all the time. In my own life, it’s been a constant back and forth.

There’s another tension in the book. How do you reconcile your personal perspective — having grown up a middle-class Italian American, Jewish man — and representing workers’ lives?

I did grow up lower-middle class, but my mom’s family had money. So [when] working very low-wage jobs, I always knew that I had a safety net, and that’s not the case for a lot of working-class people. Part of what the book is about, many characters are sort of downwardly mobile. They grew up in the [middle] classes, but they’re slipping, and that’s an experience I can identify with.

While you do touch on race, your main characters are mostly men.

I think in some ways [the book] is about masculinity as well. The prison of masculinity, for lack of a better word. The characters are not particularly sympathetic. Some of them are quite toxic. I hope that men reading it can see how ugly that is, can begin to try something else.

The event description for your reading at Town Hall asks: “What does it mean to labor in modern-day America?” That’s a huge question. Did you find some answers?

I certainly do not have the answer. It's a very specific world that's being depicted in this book. The modern-day, low-wage worker is most likely to be a person of color, most likely a woman. Many immigrants are doing the lowest-wage jobs. None of that is me. I have observed and worked with some of these [people], some of these jobs. I tried to organize some of these workplaces. I have spent a lot of years working in various forms of service work. I didn’t see a lot of writing about being a low-wage worker, and thought it was important to represent those experiences, not only my own. I care very much about people who are working hard jobs, and if my work honors them, then I feel good about that.

![]()