Using the same emissions models as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, researchers from the Union of Concerned Scientists found in a new study that if we do not implement emissions reduction strategies, the Pacific Northwest by the end of the century will see an average of 37 days per year with a heat index above 90 degrees Fahrenheit, and 10 per year with a heat index above 100. That’s less of an increase than in other areas of the country, but of the Northwest states Washington will be hit the hardest.

Washington historically sees only four days per year on average where the heat index reaches 90 or above. By midcentury, without emissions intervention, this number would stretch to 17 days; by the end of the century, 35.

In a scenario where the world meets 2015 Paris Agreement measures, we’d see an average of 15 days above 90 each year.

“The heat extremes forecast in this analysis are so frequent and widespread that it is possible they will affect daily life for the average U.S. resident more than any other facet of climate change,” the authors claim. The Union of Concerned Scientists report evaluates county- and even city-level data for the entire country, based on a number of climate data sets, that shows how temperatures may pan out to the day.

The authors focused on how the heat index — the National Weather Service’s “feels like” temperature metric, which takes things like humidity into account — will change over the coming century.

“When I look at sort of these maps of areas that are prone to heat stress today and will continue to be more prone in the future, I basically cross them off as places that I don't want to visit,” says Dr. John Abatzoglou, an author of the study and a climate researcher with the University of Idaho.

According to the National Weather Service, days where the heat index is above 90 degrees merit extreme caution, and correlate with heat stroke, heat exhaustion and other medical dangers, especially where exertion is involved.

“It definitely takes a toll on the human body in terms of potentially making one more susceptible to other impacts, like viruses and, at least for me, it impacts my ability to sleep,” Abatzoglou says.

Above 103 degrees, those dangers become likely, especially for vulnerable populations such as the very young, old or ill. That’s what’s happening across the East Coast and central U.S.

“Nobody needs to die in a heat wave and almost all the deaths are preventable,” says Dr. Kristie Ebi, a professor at the University of Washington who researches things like heat-wave-related mortality and co-authored an Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change special report. Ebi notes that for the critically ill or infirm, reports show that some deaths are expedited by one or two days as a result of heat waves. Hospital admissions rise with extreme heat events in the Seattle area.

Temperatures in Washington won’t reach those of, say, Texas, but health impacts will still be significant because of how we live and what we’re used to. Seattle doesn’t see extreme heat too often, and the kind of heat it does experience is a “dry” heat, says Dr. Zachary Zobel, an extreme weather expert with Boston’s Woods Hole Research Center.

“The way you’ve got to think about heat is that it’s all relative,” Zobel says. “The human body does have the ability to adapt to its current climate. However, if you start getting temperatures well outside the norm — and Washington is not immune to this — you can’t adjust as well. A day at 90 degrees in Seattle just doesn’t occur very often, so 90 degrees is still a big deal.”

Preparedness for that level of heat varies throughout the state. Seattle is the least air-conditioned metro area in the country, according to a 2015 U.S. census survey. Only one in three houses boasts central air or a cooling unit, and air conditioning is less prevalent in lower-income and rented homes.

“These sorts of impacts, you may be able to adapt to them if you're of a certain socioeconomic status,” Abatzoglou says. “Other people may not.”

According to Barb Graff, director of Seattle’s Office of Emergency Management, the city has gradually outfitted public spaces with air conditioning and created messaging (including a heat-wave-themed Spotify playlist) that warns people to pay attention to weather forecasts and limit their stress on warm days. Last year, the city opened at least 74 different cooling centers on warm days.

“Heat is a concern because the built environment was not originally constructed to deal with extreme heat,” she says. “I'm a Northwest native, and we have been blessed in all of my six decades on this planet with relatively moderate swings in cold and heat, and so when we have a ‘heat wave,’ it's pretty unusual and usually short lived. [But] with more frequent events and with more and more people moving here, we've got more of the [vulnerable] populations — more seniors, more people with underlying health conditions of some sort that are heavily impacted.

“Bottom line, more people are exposed to the danger of heat.”

In past heat waves, a lack of air conditioning has correlated with widespread death. More than 70,000 people died in Europe’s 2003 heatwave.

One thing that makes Seattle more resilient to heat is its cooler nights. But those could be at risk, too. Simulations provided by the University of Idaho show that minimum daily temperatures will increase even under moderate-emissions scenarios.

“In the Northwest, our nights generally cool down, so from the human body perspective that allows us to recover,” Abatzoglou says. “Some places in the United States see those heat indices remaining high throughout the night, and for people that do not have access to air conditioning [or] cooling centers, that can really end up taking a toll on them.”

Heat effects go beyond human health: Its cumulative impact on physical infrastructure can present problems for emergency responders. Graff says past heat waves caused the steel in Seattle drawbridges to swell and jam — preventing boats from passing under or cars and emergency vehicles from passing through. She also notes electric utility lines can be compromised during heat events.

Some parts of Washington will warm more significantly than others. Communities east of the mountains that don’t benefit from cooling marine weather patterns are also at low elevation and surrounded by desert. Yakima, the Tri-Cities and Walla Walla — areas with lots of agriculture — will suffer the most.

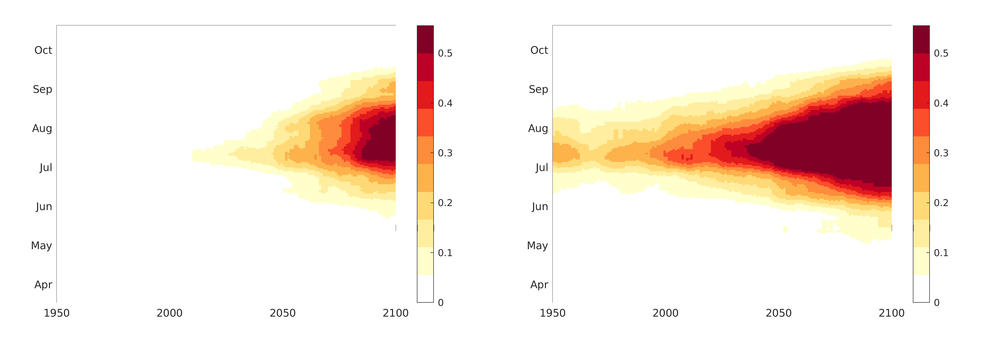

These graphs of heat index projections for Seattle, left, and Spokane under a business-as-yesteryear emissions scenario were provided by Dr. John Abatzoglou. They show that heat will not only worsen with time, but also that heat seasons will extend into cooler parts of the year. The lighter the hue, the lower the probability of a day over 90 degrees.

Dr. June Spector, who studies and teaches environmental and occupational health at the University of Washington, notes that even healthy farmworkers who spend all day exerting themselves in the fields will be at huge risk during heat events — especially when working in poor conditions under stress, within power dynamics that discourage them from taking breaks. Spector has found that in the Pacific Northwest, Washington field workers are more vulnerable to heat stress than those in Oregon.

While the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s official guidelines say 91 degrees is the lowest limit of heat index concern for employers, studies show that heat stress risk starts at 85 degrees, and is a more reasonable baseline for preventing heat-related illnesses in the workplace.

Some places in the state — mostly in higher elevations within the Cascades and coastal counties like Clallam and Jefferson — will see a much smaller bump in heat increases. But it would be a mistake to look toward these “heat refuges” as an escape from climate impacts.

“It's not, certainly, one of the highest concerns for us moving forward … but we are concerned that we have an older population,” says Willie Bence, Jefferson County’s director of emergency management. Jefferson County has the oldest population in the state. That population is, he notes, mostly retired. “We have the luxury of having folks who are retired and can spend the day inside or don’t have to maintain their livelihood by continuing to work,” he says.

But even modest heat increases bring another risk: wildfire and the smoke it brings. Though smoke and heat shelters may not be needed for decades, Bence is discussing providing them with his colleagues.

“Everyone saw what happened down in Paradise, California, last year… and all of a sudden due to the changing climate [fire is] encroaching on areas we didn't think was possible, so a lot of folks are concerned that we're going to see an event like that,” Bence says.

“The air quality isn’t going to be great and, again, given our older population, they're going to be a little bit harder than that, harder than the rest of [Washington],” he says. “I've worked in areas where air quality really is truly atrocious and clean air shelters are needed, and I don't think that's particularly likely here. But we're just making sure it's an option.”

Ultimately, while the level of heat disruption may vary across the state, nearly all areas will be exposed to some form of climate vulnerability.

"You can avoid the heat index [in the mountains or on the coast], but you may not avoid other climate hazards that we expect to occur more often in the future,” Abatzoglou says. “And when we're thinking about heading to the hills to avoid heat stress, well, you're going to head to the hills and you're going to get caught up in fire [or rising seas on the coast].”

Correction: This article was updated on July 29th at 12:37 p.m. to accurately reflect the IPCC's relationship with emissions models used for the UCS report; the IPCC's name; and Dr. Ebi's contributions to IPCC research.