A tight-knit community of about 5,000 people lives in the 24-mile Methow Valley, which extends from Pateros to the Cascade Crest. Winding roads connect small towns like Twisp, Winthrop and Mazama. Neighbors are often miles away, but most students in the valley attend Liberty Bell for middle and high school.

But for Thornton-White and Sukotavy, the essence of life in the Methow comes from the wide expanses of nature found nearby. They run on the same track team — Thornton-White sprints, Sukotavy runs long distance. They’ve jogged on mountain trails all over the valley.

“It's quiet,” Sukotavy says. “But not in a quiet way, because the birds are chirping and at night you could stay up because there are frogs, other insects and things.”

“I had the most amazing childhood growing up here — we would be swimming in alpine lakes every other day,” Thornton-White says. “I can’t imagine growing up in a city, honestly.”

But in August, everything changes. The hilly green Methow dries out and temperatures in the upper 90s transform it into a breeding ground for enormous wildfires. Summer track practice moves indoors, outdoor workers wear masks to survive the smoke and the area is swarmed by hundreds of firefighters.

“There were days when the sky was so bad from smoke that you couldn't make out the sun,” she says.

Wildfire season always has been part of life in the Northwest, but the intensity of fires the past few summers has announced itself to all Washingtonians. Even people on the coast expect weeks of smoke. Face masks sell out of department stores, and ashes fall from the sky. Last year, wildfire risks prompted Gov. Jay Inslee to declare a state of emergency.

But wildfire in the Methow Valley is different. While Seattle might experience wildfire smoke largely as a nuisance, the Methow’s crisis is more acute: The fires have made it impossible to go outside, forced evacuations, burnt down homes and taken lives. The broader climate impact lasts beyond fire season: The valley faces possible water shortages due to decreasing snowpack, and aggressive flash flooding.

Organizations like Methow Ready have formed to respond to increasing interest in protecting homes with fire safety measures. But Thornton-White says the threat is at their door, and she wants more people to pay attention.

“What made the news this past year was: Seattle has the worst smoke, worst air quality in the country,” Thornton-White says. “And then here it was about 10 times worse.”

Seeing these environmental hazards in the home they love, Thornton-White and Sukotavy helped form an activist group in the Methow to give voice to the experiences of kids who grow up in these conditions.

Thornton-White, the group’s main organizer, and Sukotavy are joining a chorus of youth climate activism that’s taking the country (and world) by storm. Increasingly children are seen as leaders in the climate fight, from Sweden’s Greta Thunberg to Seattleite Jamie Margolin, who last year led Zero Hour, a nationwide march for climate action.

If those youth efforts are aimed at maximizing global awareness and momentum in the climate fight, Thornton-White and Sukotavy hope to localize it. Armed with first-hand evidence, members of the Methow youth climate activist group brought their stories to the state Legislature in April, vouching for the passage of environmental bills like the statewide plastic bag ban and Washington’s mandate to achieve 100% clean energy by 2045. And last month, instead of joining statewide youth climate marches, they organized a climate march in Twisp, a town in their backyard that saw an 11,000 acre fire in 2016. They say it’s the least they can do for Eastern Washington communities that are in direct environmental danger from wildfires, flash floods and water shortages.

Thornton-White says caring for the environment wholistically, through plastic bans and support for solar energy, goes hand in hand with drawing attention to the threats the Methow already faces. She says it’s critical that young voices are involved in these discussions, too.

“It's kind of become normalized and I don't think that's right,” Thornton-White says. “Especially since they're becoming increasingly worse and worse, the fires. That's definitely a motivation for me.”

Members of the Liberty Bell Junior Senior High School track team do laps around the track during practice on April 18, 2019. Both Sally Thornton-White and Icel Sukovaty are on the team. During wildfires the smoke has gotten so bad that the athletes can't use the school's track, so they have relied on a community gym to let them use their stationary exercise bikes.

'Everything I've ever known'

Environmental advocacy isn’t new to the Methow. The organization that helped launch Thornton-White’s legislature campaign, the Methow Valley Citizens Council (MVCC), was born when developers tried to bring a massive ski resort to the area in the ’70s. The developers eventually backed down in the ’90s, after decades of local protest. Since then, the MVCC has served as one of the area’s largest nonprofit environmental watchdogs, focusing on land, water and air issues.

“It’s not by accident that the Methow is the way that it is,” says Jasmine Minbashian, the organization’s executive director. “It’s because a bunch of people who cared came together and made sure it stayed that way.”

Thornton-White’s parents both studied environmental law; steeped in these issues since childhood, she decided to intern with the MVCC and organize a youth climate lobbying day at state Legislature for her senior project. She enlisted her best friend, Sukotavy, to help round up volunteers, ask teachers to hand out flyers for lobbying day and convince classmates to go to Olympia. In the end, 11 seniors, sophomores and one student who had graduated the year before traveled to Olympia on March 11. It was the first time any of the students in the group had stood before state legislators.

When the students did so, they conducted an exercise. Thornton-White initiated, asking her peers a few questions: How many of them had been evacuated from their homes once?

Every Liberty Bell student raised a hand.

Twice?

All of them raised their hands again. Some added that they’d lost parts of their homes, too.

When the legislators heard this, Thornton-White says “some of them actually started crying.” She says most weren’t aware of how the young people she knew had to deal with the fires up close. Each student had a story of their own: Lazo Gitchos says his family once evacuated, leaving their farm behind. They hopped from Idaho to Seattle in repeated attempts to dodge the smoke. Leo Shaw says his father, a landscaper, could barely work when the smoke was at its worst.

Sukotavy’s story began in August 2014, during the height of the Carlton Complex Fire. While that fire burned through hundreds of thousands of Washington acres, a separate blaze inched closer to her home and family farm.

Sukotavy was taking care of a 6-year-old and 9-year-old, the children of workers on her family’s farm, while the fire grew. She could see the fire from the edge of her family’s property, distant but still frighteningly visible.

At one point, her mother handed her their dog’s leash and told her that if she saw flames come over a hill about 200 meters away, she should take the children and the dog and run. They would need to head to the nearest designated safety zone — in this case Liberty Bell, right across the street from her farm. Hundreds of tents covered the school’s playing field: Firefighters from across the country (and even some flown in from New Zealand and Australia) had made their basecamp there.

From wildfires to flash floods, Sally Thornton-White and Icel Sukotavy have seen firsthand what a changing climate means for their home in Washington's Methow Valley. (Video by Beatriz Costa Lima/Crosscut)

Sukotavy had shrugged off real concern about the wildfires before that moment. In the weeks leading up to it, she remembers wearing a face mask and posting Instagram stories about how she couldn’t see the sun overhead through the smoke while she worked on her family farm’s irrigation system. This time, with smoke everywhere and the children at her side, she felt real fear.

“Looking back on it, I realized that I was probably being way naïve,” she says. “Because that's not something that's normal. That was my childhood home — it’s everything I’ve ever known.”

“I was just blown away by how real it was.”

Shortly after, Sukotavy’s family moved the rabbits, chickens, sheep and other animals in danger on their farm to safer places. Thornton-White’s mother, Jeanne White, joined other community members and family from around town in an effort to help shelter the animals. She already had sent her daughter to stay out of state with grandparents, away from the smoke.

“That was a crazy day, [with Sukotavy’s] mother Jennifer, who is my friend, calling me and saying come help and trying to get animals out of the way while there were helicopters overhead and the fire was coming down the hill,” White says.

The smoke couldn’t be helped, but with the help of neighborhood volunteers, Sukotavy’s family successfully moved the animals onto pastures surrounded by irrigation, where the fires wouldn’t reach them. It took all hands to make it happen.

Right: Growing up in the Methow Valley, Sally Thornton-White says she has seen a decrease in fish population, a melting snowpack and plastic in remote parts of the mountains. "This is a place I love and want to come back and raise my kids and, with the rate of climate change, that might not be possible," she says.

The aftermath of the Carlton Complex fire lasted long after the flames were put out. Ground shifted and eroded by fire turned into house-destroying mudslides when the rains came. More than 256,000 acres of land were damaged, and fire suppression costs exceeded $90 million. The drive toward the Loup Loup Ski Bowl between Omak and Twisp is still marked by hills and hills of razed woods. Sukotavy and her mother call the blackened and branchless trunks left behind “pins and needles.”

The following year, the Okanogan Complex Fire took the life of someone Thornton-White knew personally: 20-year-old firefighter Tom Zbyszewski, who graduated from Liberty Bell in 2013. He had fought wildfires for three summers with the Methow Valley Ranger District in between attending Whitman College in Walla Walla, where he was about to become a junior physics major.

“My mom was his swim coach,” Thornton-White says. “I will never forget the moment my mom heard that he died — she broke down.”

He was someone involved in the community — someone everyone knew, she adds. Thornton-White says people outside the Methow often “look past that and they don't really understand how it affects this community.”

“People might kind of know what's going on,” she says. “But it's never put into context until someone truly shows the connection to what is happening and shows why it's important to them.”

Protecting what you love

On the April 19 climate march in Twisp, more than a hundred locals with signs and costumes gather next to the nonprofit community organization TwispWorks. The crowd is a mix of valley residents, from council members to students to shop owners from down the street.

A handful of locals come dressed as salmon, but most hold signs with slogans like “Make The Earth Great Again” and “More Wind Power, Less Wind-Bags.” The Liberty Bell students hold their own sign, a large banner that reads: “Protect What You Love.”

Twisp’s main drag is less than two miles. A direct route to the march’s endpoint at the community center covers less than half a mile, about three or four blocks. The marchers snake their way through most of town instead. A handful of bystanders watch the crowd of nearly 200 march past cars and storefronts. As the marchers cross the street toward the community center, some people sit in their cars and watch the group pass.

They gather for food and festivities in the community center, while booths from organizations like Methow Ready hand out flyers, telling residents how they might protect their homes in coming years. Attendees talk and circle the booths, eating tacos from the food truck outside. A table full of students signing up to vote sits in the middle of the room, with signs prompting young people to make their voices known through civil action. Sukotavy is among them.

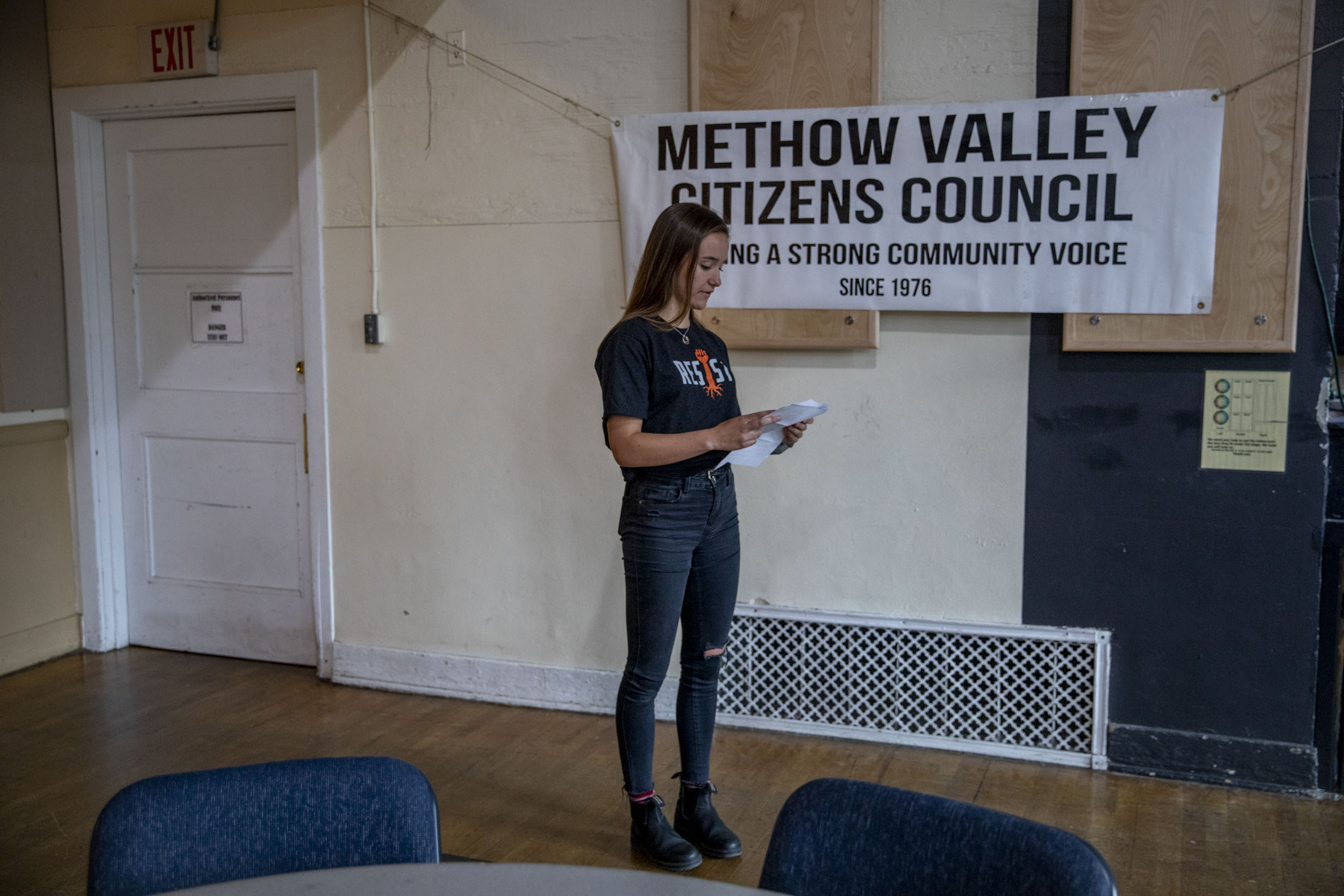

A moderator calls Thornton-White to the stage. She takes the microphone and tells the story of the student group’s visit to the Legislature, how they all shocked legislators by describing the conditions in the Methow Valley and how she herself came away surprised by their shock.

“Never before had I realized this was odd,” she tells the room. “Because over the past years, I've become accustomed to fires filling our summers. To me, power outages and Level 2 evacuations have become nothing more than your average August day.”

It’s not something they should settle for, she says, and the crowd applauds. Her mother, who helped set up the booths and decorations before the event, stands among them, crossing her arms and smiling at the stage.

White first moved to the Methow from Colorado with her husband just before Sally’s birth in 2001. She wanted her daughter to grow up in a place “that was like Colorado, but Colorado 30 years ago”: pristine, quiet, resilient. The fires weren’t something she’d even thought about. She didn’t need to.

“I live where I have irrigation water and I don't have trees around me,” White says. “So maybe I have a false sense of my own safety.”

White says that since the Carlton Complex fire in 2014, area homeowners have become more concerned about the safety of their properties. Kirsten Cook says that when she began to oversee Okanogan County’s Firewise program in 2012 — a national assessment program that teaches people living in wildfire-prone areas how to adapt — she conducted about 10 assessments each year. Now, she conducts about 100.

“Firewise has kind of become a household name — like Kleenex — in the Methow,” she says. “Awareness [of the program] is significantly higher than it used to be.”

Okanogan Fire District 6 Chief Cody Acord adds that while large fires occur in the Methow Valley, he’s seen larger fires in recent years and noted “more coming down closer to residential areas.”

When White thinks about her own high school experience compared with her daughter’s, she knows her daughter’s memories of middle and high school will always include summers of smoke, fire and firefighter basecamps.

“I think it's becoming more pronounced, the changes,” White says. “What will that be like in 10 or 20 years? I don't know. Will we ever be able to feel normal? I don't know. We haven't felt normal since 2014, I can guarantee you that.”

“I want your generation and my kids to have hope — I want them to be able to have the same stuff that I've had,” White says. “I don’t want you guys to think about not having children.”

Thornton-White and Sukotavy will soon embark on another adventure together, but apart: They’ll soon go to college, where they both hope to study environmental science. Thornton-White is off to the University of Denver while Sukotavy will go to the University of Rochester.

It’ll be the first time they’ve left each other and the valley for a long stretch of time. Thornton-White is cautiously optimistic about the Methow’s fate this summer — with cold and rainy weather so far, she hopes that it won’t be a bad wildfire year. But she does admit she’s a little nervous about being away from her friends, like Sukotavy.

“But we come from such a close community,” she says. “I know that I will always have them to come back to. I also know that I won’t lose contact with Icel and she will always be my person.”

Sukotavy isn’t worried about the distance either. “Some friendships are as easy as breathing, and that’s what we have,” she says.

The community-led Methow Valley Climate March moves through downtown Twisp on April 19, 2019. (Video by Beatriz Costa Lima/Crosscut)

The pair hope the two sophomores in their student climate group will continue meeting and recruiting new members next year. Thornton-White also will be one of two youth ambassadors for the MVCC’s climate action plan committee, where she’ll consult with a group that includes mayors from the Methow’s three largest towns and area environmental experts. The group hopes to have an organized plan by early next year to allocate community resources in response to future climate crises. it would be among the first of its kind for a small rural community.

“In some ways, I think the Methow is really pioneering what it means to be a small, rural, ag and forestry and tourism-based economy, and have to adapt to climate change,” MVCC director Minbashian says. “The personality of this community is not really to be a victim, and we [need to] come up with a really good plan for living in the valley in the face of wildfires and water shortages and smoky summers.”

While Thornton-White will leave for college, she also doesn’t feel like she’ll ever really leave the Methow behind. One day, her and Sukotavy’s efforts to help the Methow and the state adapt to climate change could have full-circle implications for her own family.

“I definitely can see myself ending back here — it was pretty magical,” she says.

“I want my kids to have the same opportunity.”