“I think that most people think of the fishes out there as kind of gray and brown, because when you bring them out of the water they lose their colors within minutes,” says Pietsch, who taught ichthyology for 40 years at the University of Washington and curated the Burke Museum’s fish collection, the largest in North America as it holds more than 11 million specimens.

As he moved forward teaching and curating, Pietsch felt limited by textbooks he used for his classes. In particular, he was upset by the dearth of research and accurate illustrations about local marine life available to him and his students.

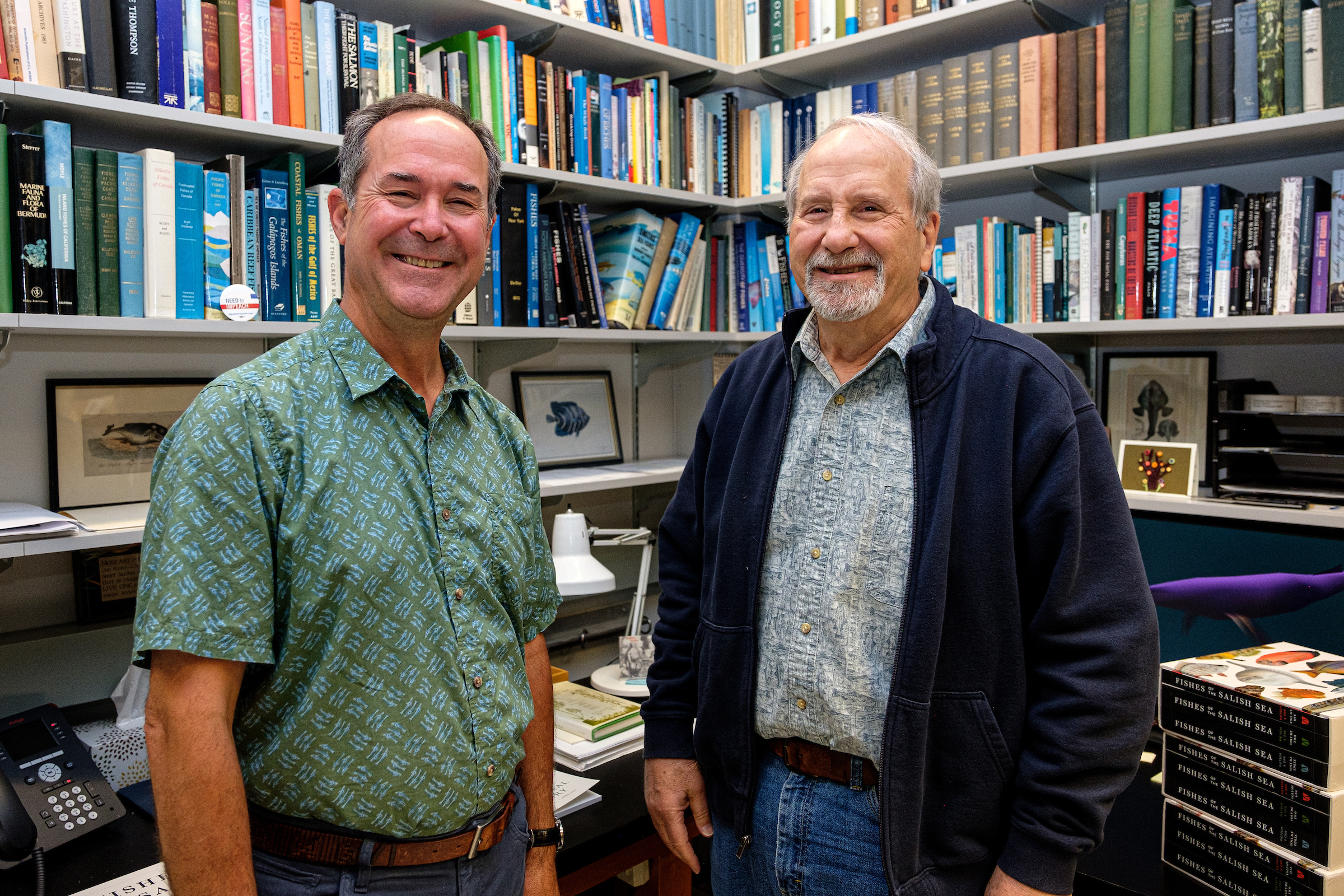

Then, in the 1990s, he met Orr, then one of his graduate students. Orr, who would go on to become a researcher at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, also took interest in the local fish population. Together, the professor and his student began plotting a total overhaul of existing knowledge of fish in the Salish Sea: a marine region in Northwest Washington composed of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the Strait of Georgia and Puget Sound.

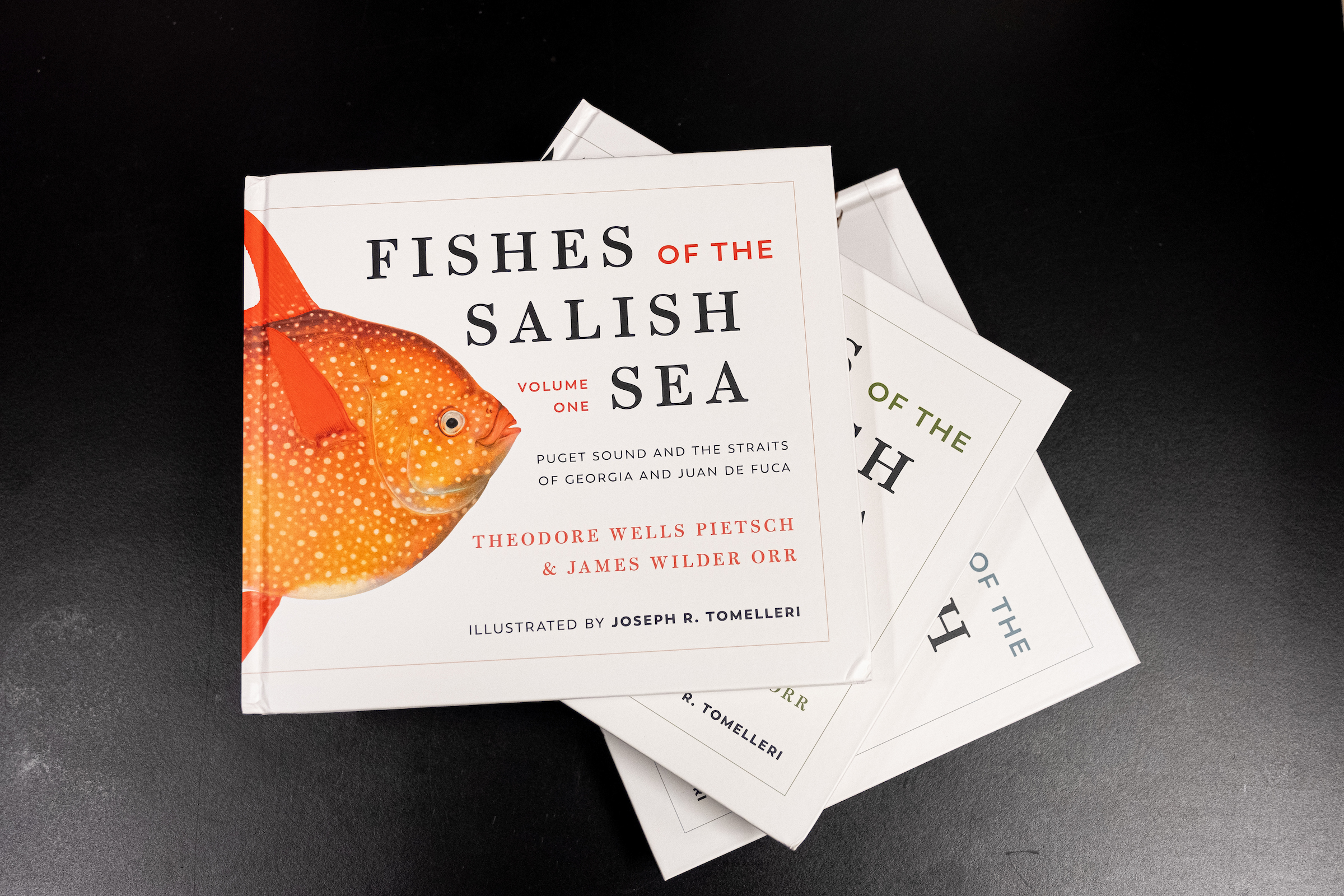

They envisioned that their work would take the form of a large book that would provide insights into fish ecology, history and geographic distribution, as well as a strong visual reference.

To illustrate the book, they considered photographs, but the quality was mixed. Illustrations, they decided, would allow a more compelling single specimen to represent each species.

“We wanted our book to be beautiful as well as accurate and useful, so that really put us off for the longest time,” Pietsch says.

Three decades later, they’ve produced Fishes of the Salish Sea, a 1,032-page “doorstop” of a book that comes in three volumes. It’s both an encyclopedia, organizing species from least to most evolutionarily advanced, and a historical review of how species were identified, beginning in the 1880s. It includes artist Joseph R. Tomelleri’s hand-drawn illustrations, nearly 50 of which will be on display at Arundel Books through Aug. 1.

The book heavily advances ichthyology in the state. When Pietsch started at UW in the 1980s, the running tally of fish species confirmed in the region was about 218. By the time he and Orr finished, they had established 260 species, increasing the known number of species by 15%.

Amanda Whitmire, head librarian & bibliographer at Harold A. Miller Library within Stanford University's Hopkins Marine Station, was thrilled to hear of the book and order it for her collection.

"Fishes of the Salish Sea is one of those sets of books that I love to buy. It hasn’t arrived yet, but I’m really looking forward to seeing it in person. When I read the description of the book, it sounded like a wonderful combination of natural and local history, ecology and taxonomy — any one of those things combined with the gorgeous artwork would have been enough," Whitmire says via email. "As I’ve been working through Hopkins’ historical materials, the stories behind the people who were doing the work are what bring old data to life."

Orr says the university is planning to publish a digital edition, as well as an abbreviated field guide.

The book took decades in part because the researchers had to fact-check everything ever published about each species “and go into the collection itself and sit with microscopes and study the actual specimens because there's so much incorrect information out there,” Pietsch says. “If someone says, ‘Oh this thing has 14 dorsal fin rays,’ everybody just copies that for decades when really that first person made a mistake.”

This process resulted in a unique understanding of how dynamic our waters are. El Niño temperature shifts bring new tropical fish up from the South; some species are only ever recorded once.

“You don't say, here's what's here, here's what has been here, and here's what always will be here. Things disappear and things come into our waters,” Pietsch says.

This kind of knowledge is essential, say the scientists who spent decades carefully collecting it, especially in the age of climate change and widespread pollution. (Photo by Caean Couto for Crosscut)

“If we don't know what's there, we don't know what might be lost along the way,” Pietsch says. “It's really crucial.”

“All these animals are important to the ecosystem in complex ways we simply don’t understand,” Orr adds. “You can't understand the system unless you know its elements.”

Now readers — from academics to hatchery managers to fishermen — can all get deeply acquainted with that system without stepping foot in the water. But for those who might blanch at flipping through a 13-pound tome, we present a truncated list of 10 Northwest Washington fish that tells some of the story.

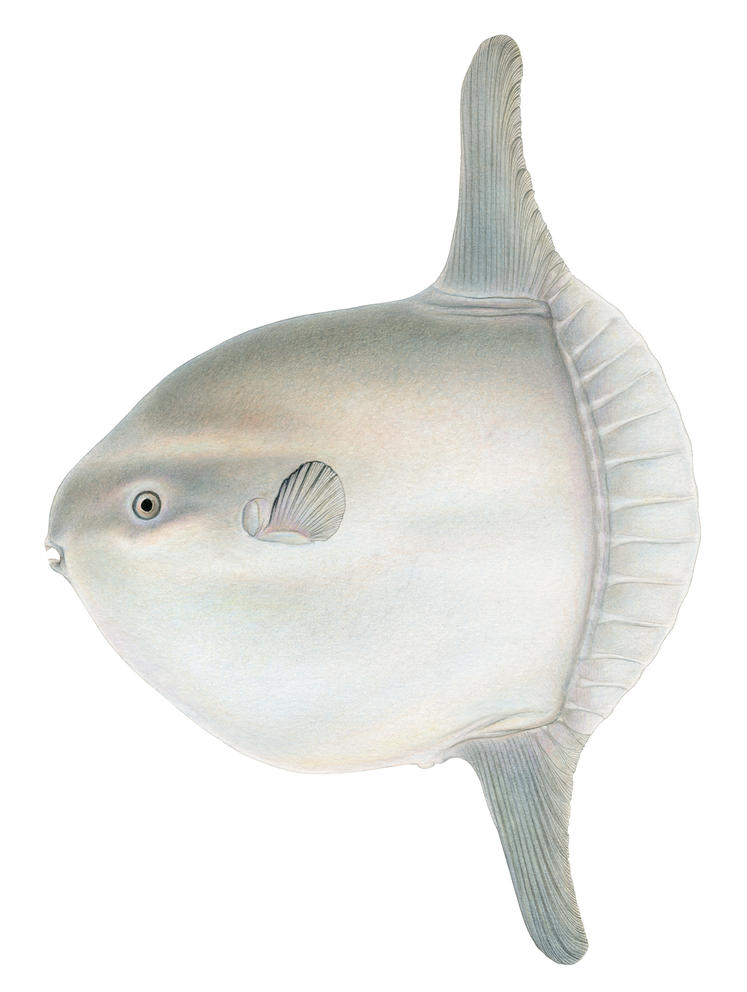

Ocean Sunfish: The Living Landing Pad

When not drifting along currents in pursuit of jellyfish, the Ocean Sunfish (mola mola) suns itself on the surface of the water, like a scaly lily pad. "They'll be lying flat, this huge animal that's 20-feet across [and 500 pounds] — just drifting on the ocean surface — and seagulls will be landing on them, plucking off barnacles and things. They're amazing,” Orr says.

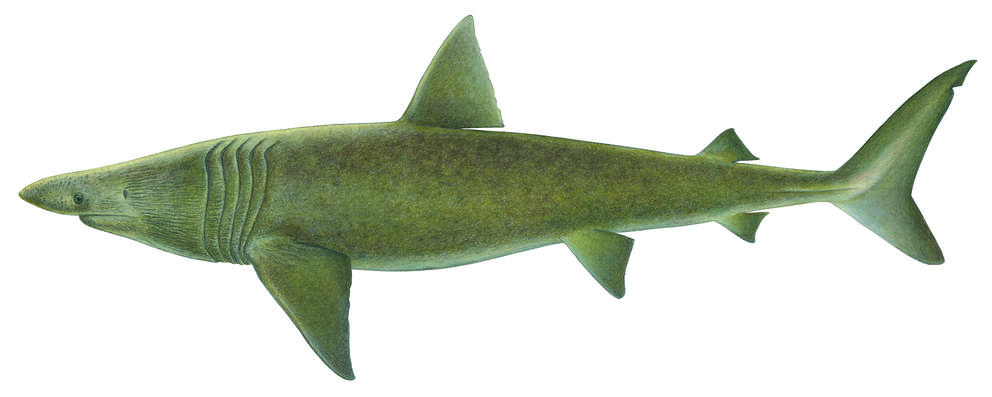

Basking Shark: Big and Butchered

The largest fish ever documented in the Salish Sea is the Basking Shark (cetorhinus maximus), which in other locales grow to be 50 feet long. “It's kind of unclear how big they got in the Salish because it's so hard to measure big animals,” Orr says. They used to be plentiful, but “unfortunately at one point they were considered pests to Puget Sound fisheries, so the Canadians set up a ram [on boats] to actually slice through them in the ’50s.”

Grunt Sculpin: Tiny Ocean People

The Grunt Sculpin (rhamphocottus richardsonii) stands out for its patently strange looks and method of transportation, confounding the traditional conception of fish as swimming beasts. Rather than scull through the ocean, the Grunt Sculpin (so named because it actually grunts) pushes itself along on its fins. “They walk around on their pectoral fins, and look like little people,” Orr says. “It's a really neat fish.”

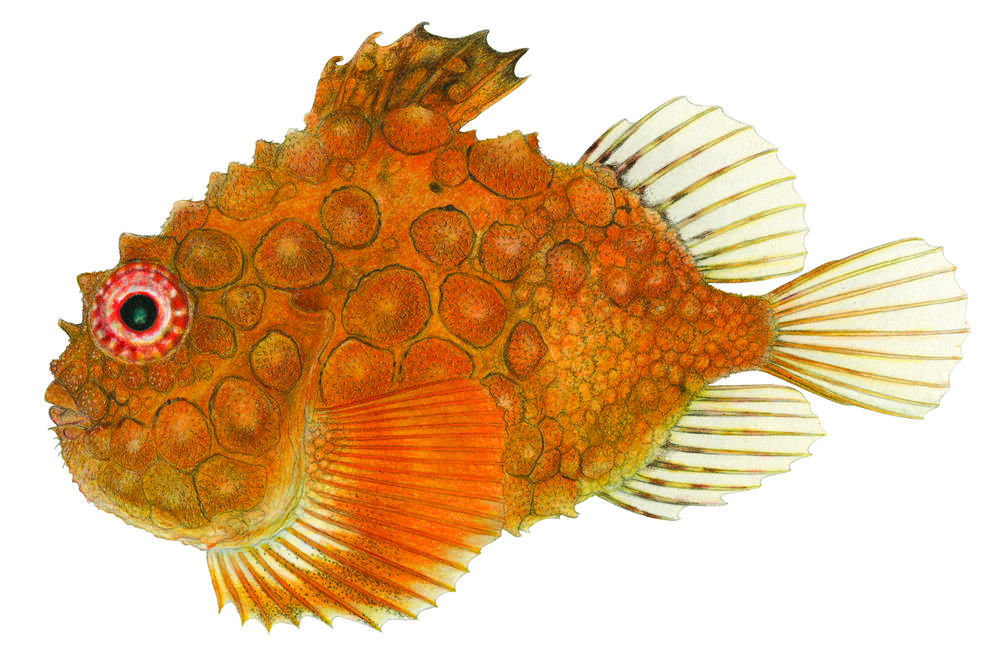

Pacific Spiny Lumpsucker: A Cute Fish with an Un-Cute Name

“Folks around here call it the cutest fish in the sea,” Orr says of the Pacific Spiny Lumpsucker (eumicrotremus orbis). “They're little balls with a sucking disc, and they'll suck onto rocks and stay there in the currents and sort of bounce up to catch little invertebrates, and suck back on again.”

Blacktail Snailfish: The Scourge of the Kings

Scale-free Blacktail Snailfish (careproctus melanurus) live in deep waters and are so fragile as to be difficult to study, Orr says. “They have thin skin and a layer of mucus underneath that strips off, and … their bones are not as hard as [those of] other species groups,” he says. “They come up mangled.” Where they do thrive is inside king crabs. Female snailfish deposit their eggs inside crab shells, and “when they hatch, juveniles will actually use the crab as protection until they get too big. … It's really a crazy relationship,” Orr says.

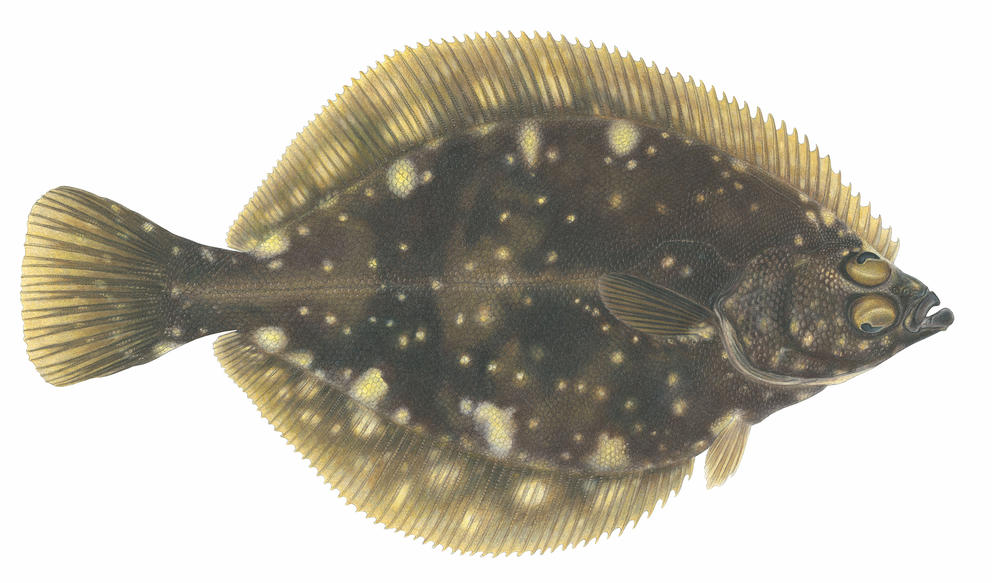

Northern Rock Sole: A Scaly Flat Stanley

Flatfish like the Northern Rock Sole (lepidopsetta polyxystra), which Orr himself named, have one of the most exciting developmental cycles in the Salish Seas. They start their lives swimming freely just like any normal fish, but as they age, their body flattens like a deranged Flat Stanley of the Seas, and the animals sink to the seafloor. “Before they settle to the bottom, one eye starts to move — in this case it moves to the right side of the head,” Orr says. This particular species is ecologically interesting to him because it can live in lots of different places, eating many different things.

Pacific Sand Lance: Ostriches of the Ocean

Just as scared ostriches are erroneously said to do on land, these 6-inch, arrow-shaped fish hide from the world when threatened by piercing into the sandy seafloor. “If you’re diving and you disturb a school of these things, they'll all en masse dive into the bottom and bury themselves,” Pietsch says of the Pacific Sand Lance (ammodytes personatus).

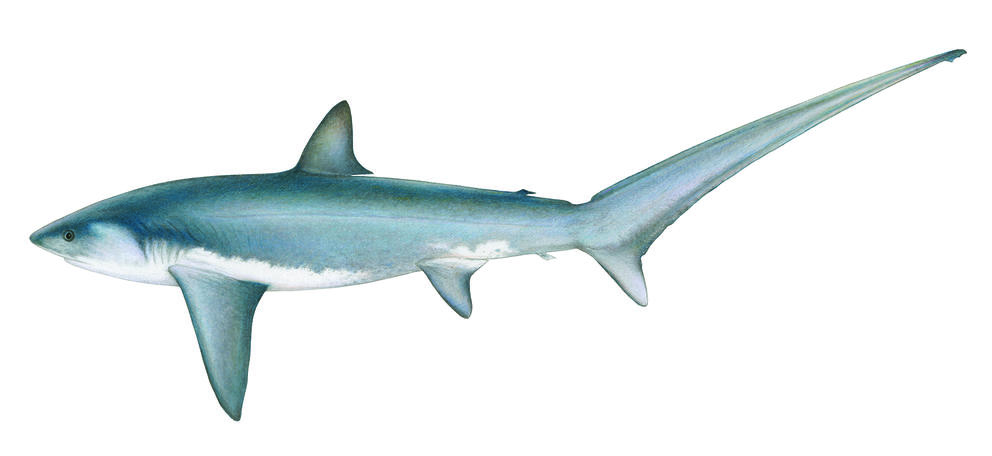

Common Thresher Shark: Farming the Ocean’s Fields

Schools of fish give Threshers (alopias vulpinus) a wide berth wherever possible, due to the shark’s abrasive feeding habits. Like the farming machine of the same name, Common Thresher Sharks separate out fish from their schools by beating them with their long tailfin, which can be as large as the rest of the shark’s entire body. “It's a really strange shark,” Pietsch says. “They enter schools of smaller fish and wag this tail, like a whip really, and they stun and break apart little tiny fish in schools, disabling all these little things, [even] killing and maiming them. And then they go back and gobble up all the things they've destroyed.”

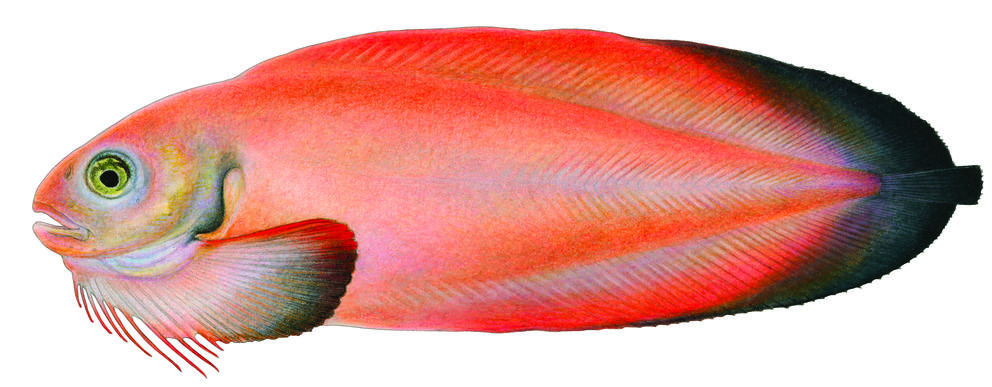

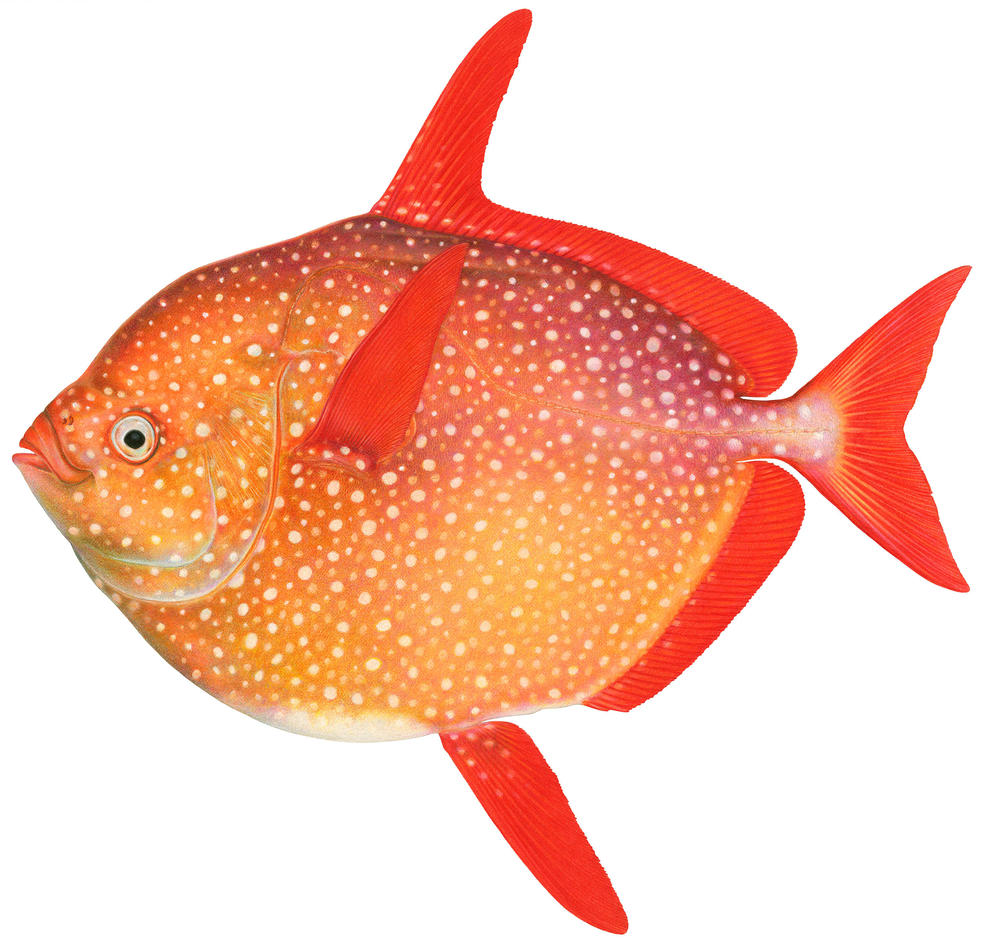

Opah: Marine Birds

As with the Grunt Sculpin, the Opah (lampris guttatus) challenges perceptions of what it means to be a fish. Four feet long and thin like a disc, the Opah moves through the ocean in a sort of flight. “It's really kind of unusual because its pectoral fins on the side of the body are situated so that when they are move up and down, like the wings of a bird, the fish actually flies through the water rather than scull along like other fishes do,” Pietsch says. “And they're awfully good to eat, too, although they're so few and far between. They're certainly not commercially available.”

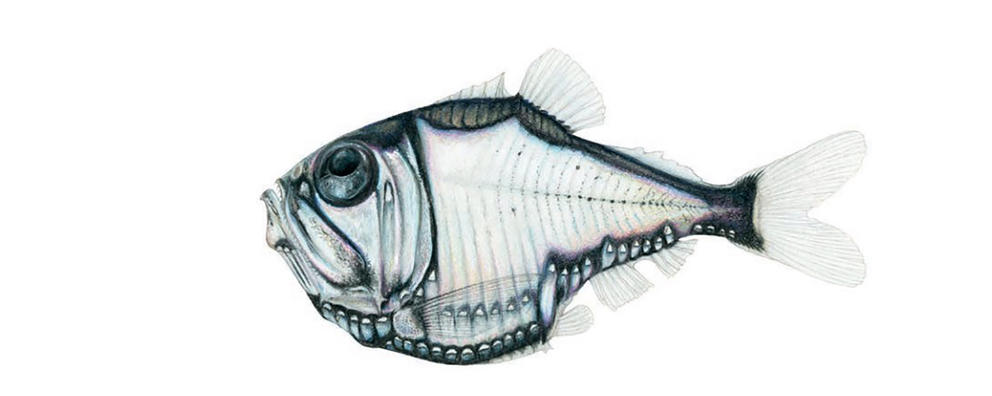

Lowcrest Hatchetfish: Bright Ideas

The deepest part of the Salish Sea plunges more than 2,100 feet, far beyond the sun’s luminous rays. The darkness has helped create a ghoulish assortment of deep-sea animals: bioluminescent fish, or fish that create their own light, like the Lowcrest Hatchetfish (argyropelecus sladeni). The ability to light sections of a fish’s body, called countershading, gives it a huge camouflaging advantage, Pietsch says. Shallow-water fish have pale-pigmented bellies and dark backs because the sun’s light is strongest from above. They appear to blend into the water column to aerial predators, while light bellies keep them shrouded to predators coming from below. “The deep sea ones, where light doesn't penetrate as much, they have bioluminescence on their lower half [in lieu of pigmentation] to do the same thing. Any deep predator looking up will see the light [belly] against the down-welling light from above.”

This article was updated on June 17 at 9:31 a.m. to include quotes from Stanford's Amanda Whitmire; and to reflect that ostriches only bury their heads in the sand out of fear within pop culture, not in practice.