Frontier Seattle was a place where a person could come to escape the past. A prime example is a newspaper man who was friends with Horace Greeley and took the famed editor’s advice to come west — and who wound up in Seattle as a political refugee on the run from Civil War politics.

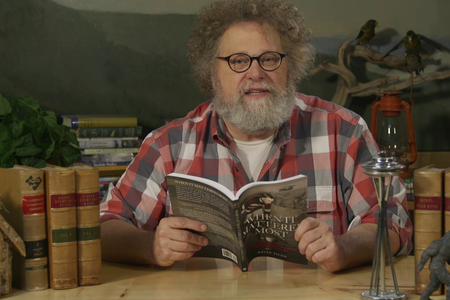

Meet Seattle’s rebel mayor, Beriah Brown.

Most histories of Seattle talk about Brown as a prominent citizen in the early years of the city’s history. He founded the city’s first daily newspaper, which would eventually become the Post-Intelligencer. He served on the University of Washington Board of Regents. And in 1878, he was elected to a single term as mayor of Seattle. The Seattle Times called him “one of the most remarkable men that ever lived in Seattle.”

But Brown had a past. In the antebellum era, he was a passionate Democrat who defended slavery and Southern states’ rights, promoted white supremacism, attacked President Abraham Lincoln in his editorials, and tried to start an all-white colony in Sonora, Mexico.

During the Civil War, federal authorities thought him to be the head of the Knights of the Columbian Star, a secret pro-Confederate society and spy ring trying to undermine the Union. Virtually none of that was written in the local history books or his obituaries. One reason: Brown came to Seattle for a makeover, a reconstruction during Reconstruction.

Brown worked for many newspapers. In his early years, he and Greeley even roomed together. Greeley stayed east as the pro-Union editor of the New York Tribune, while Brown worked his way west through jobs at a series of newspapers in New York, Michigan and Wisconsin, eventually arriving in California during the Civil War. He was heavily involved in sectional politics, a Northerner who was sympathetic to the South — commonly called a Copperhead. He even ran for Congress.

Brown railed against abolitionists as “brainless dirt-eaters”; he warned of a nation turned over to “mongrels.” He raged against the war and what he viewed as Lincoln’s despotism. Pro-Union papers called him names, including “treason-shrieker,” “snake in the grass” and “Beriah the Liar.”

Things came to a head on April 15, 1865, when news of Lincoln’s assassination hit San Francisco, where Brown was editing the Daily Democratic Press. An angry pro-Union mob looted and burned the press, Brown’s extensive library of 20,000 volumes and his personal papers. Brown fled for fear of being lynched.

After the war, Brown worked his way north into Oregon, then Washington while editing and writing for a number of frontier papers sympathetic to his views — Brown opposed Reconstruction, for example. He eventually found his way to the little town of Seattle, where he decided to start over and put sectional politics behind him.

Occasionally, his contemporaries referred to his racist past, but Seattle was a largely forgiving place for people with a past. And Brown believed in a big future for the budding city. An “exponent of progress,” he called himself. He took to railing against socialism, among other things.

When he died in 1900, he was lionized as a pioneering newspaperman and the general movement in the early 20th century to "re-unite" white America after the Civil War led some to gloss over his rebel actions and views —which, to be honest, were held by many Americans of the time. “His virtues were many, his errors few,” eulogized one newspaper colleague.

True, I suppose, if one purposely works to escape the sins of the past in an ambitious frontier town.