“I would prefer to die on this soil than go back to Russia,” Amar, an asylum seeker, had once said. According to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and the Pierce County Medical Examiner, weeks after his appeal for asylum was rejected and days before his impending deportation, Amar died by suicide. When the news eventually reached his family, it came as a shock.

For months, Amar’s family wrestled with the knowledge that a loved one had died, as well as with the bureaucracy, language barriers and the costs that prevented them from quickly obtaining information and the remains of their loved one.

Finally, the family authorized Cházaro to fill out the forms required to transport Amar’s body from the Pierce County Medical Examiner office to Funeral Alternatives of Washington in Federal Way, where, for $750, Amar, 40, was cremated.

At the post office, Cházaro was in a hurry. Amar’s family is Buddhist and believed their relative would be reborn 49 days after his death; a funeral would have to take place before then.

Cházaro had stored the urn in a box that read “priority mail,” paying $115.45 to ship 9 pounds, 5 ounces of ashes. Still, a postal worker in Federal Way said she could not be certain Amar would make it home by the 49th day, or before New Year celebrations in Russia.

Now, more than six months later, according to ICE, a completed investigation into Amar’s death is still pending. In November, Rep. Adam Smith, D-Bellevue; Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash.; U.S. Rep. Pramila Jayapal, D-Seattle; and Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Wash., asked Ronald Donato Vitiello, then acting director of ICE, for an in-depth and timely investigation into his death.

A second letter sent by the members of Congress to the Department of Homeland Security's Office of Inspector General asked officials to "conduct a comprehensive inspection and review of the conditions at the NWDC, including potential retaliation against detainee whistleblowers." Washington Gov. Jay Inslee also sent a letter that called for an "immediate, independent inspection of the health and safety conditions" of the detention facility.

It is unclear whether an inspection of the Northwest Detention Center will be conducted. In January, John V. Kelly, head of the Office of Inspector General for the Department of Homeland Security, told Inslee that his staff was currently investigating Amar’s death.

“We are also considering an inspection of the NWDC as we plan our next round of unannounced inspections of facilities housing ICE detainees,” he wrote. “Because our inspections are unannounced, we do not publicize or confirm our inspection locations in advance. We will, however, report publicly on all inspections that we conduct after they take place.”

Deaths of people detained by ICE and the U.S. Border Patrol have dominated news headlines in recent weeks. In addition, in a memo obtained last week by the news organization The Young Turks, a supervisor in ICE’s Health Services Corps told the agency’s former acting deputy director, Matthew Albence, that the unit tasked with providing health care to detained immigrants is “severely dysfunctional and unfortunately preventable harm and death to detainees" have occurred. At least nine people, including Amar, died in ICE custody last year.

Currently, there are thousands more immigrants held in detention in the United States than in years past. In May, ICE announced that it was holding a record 52,398 people in its facilities. That’s almost 10,000 more detainees than the 45,000 cap Congress approved earlier this year.

In addition, reports of abuse within the agency’s facilities are common and include the possible overuse of solitary confinement. In 2013, ICE issued a new directive on solitary confinement, noting that it “should be used only as a last resort and when no other viable housing options exist.”

Yet, on and off, Amar was isolated from the jail's general population in what the agency sometimes referred to as medical isolation or voluntary protective custody. In October, for example, according to the agency's detainee death report, Amar asked that he be placed in voluntary protective custody for "undisclosed reasons." ICE also places suicidal detainees in solitary confinement. In documents obtained by several news outlets documenting the agency’s use of solitary confinement from March 2012 to March 2017, in at least 373 instances, those in solitary were on suicide watch.

Amar is one of two detainees to die at the Northwest Detention Center in the 15 years it has been in operation. Although there has been some information on Amar’s background and what brought him to the United States, little has been known about what happened at the detention center on the day Amar hung himself and the hours immediately following his suicide attempt. A report from ICE and the Tacoma Police Department obtained by Crosscut, as well as 911 audio and interviews with Amar’s family and those who were present during his final hours, reveal previously unreleased details about the man, his journey into the U.S. immigration system and, ultimately, his death.

“We tried our best, and it’s just unfortunate.”

According to the police report, on Nov. 15 at about 3 p.m., an officer at the detention center began making the rounds, checking cells in the solitary wing of the facility. He found an unshaven Amar seated on the floor, dressed in gray sweatpants and white underwear briefs with his feet facing the door. His head was covered and a ligature, apparently made of strips of braided bed sheets, was tied around his neck.

Two employees rushed inside his cell to loosen the ligature, cutting it in two places. One end of the ligature had been tied to the corner of the top bunk. Books written in Russian were strewn on the floor.

Christopher Taisacan, an officer who has worked at the detention center for approximately three years, was part of the team that entered Amar’s cell after his apparent suicide attempt.

“Whenever there’s an emergency, officers are always concerned and trying to do the right thing,” Taisacan said in a phone interview about the incident. “I think everyone did a good job.”

“They did what they could do,” he said. “I don’t think there’s anything an officer could have done any different. We tried our best, and it’s just unfortunate.”

About 10 minutes later, an officer at the facility called 911. According to a recording of the call, obtained through a public records request, an officer explained to a dispatcher that a detainee was “unresponsive” after attempting to hang himself. Someone was performing CPR on Amar, he said. The officer said Amar was no longer warm to the touch. His skin was blue, said ICE's detainee death report. The 911 dispatcher asked when was the last time someone had seen Amar alive. The officer answered “probably 20 minutes ago.”

A half-hour later, Amar arrived at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Tacoma and was placed in the intensive care unit. The nurse told police that Amar could not breathe on his own. According to the police report, the nurse said Amar was believed to be brain dead.

Medical experts and the law say a person who is brain dead is considered dead, an irreversible condition where a patient has lost all brain function, but may appear to be alive. Amar’s heart, for example, was still beating. The nurse told police a neurologist would check for brain activity.

Michael J. Souter, a professor of anesthesiology and pain medicine at the University of Washington School of Medicine, said typically two doctors will check for brain activity over several days and confirm the patient's death.

According to ICE’s detainee death report, two days after arriving at the hospital, Amar continued to not respond to stimuli, one of several methods used to check for brain activity. On Sunday, Nov. 18, at 5:30 p.m., "all tests indicated brain death," ICE's detainee report notes. The medical team discontinued life support a half-hour later. Five minutes after that, Amar had a heart attack and was pronounced dead. The preliminary cause of death is listed as "suicide attempt by hanging, anoxic brain injury, and traumatic cardiac arrest."

ICE would later mark Amar’s day of passing as Sunday, Nov. 18, three days after he was found hanging at the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma. ICE did not release news of his death, however, until approximately a week later, on Monday, Nov. 26, one day after the Pierce County Medical Examiner office had confirmed his death. In its statement, ICE said Amar had remained on life support through Nov. 24, contradicting the agency's later report on the detainee's death, which notes he was removed from life support on Nov. 18 at 6 p.m. The agency now says the report got the date Amar was removed from life support wrong and that it plans to address the error.

Based on the agency’s own policies, ICE is supposed to release a statement about a detainee’s death within 24 hours. When asked whether ICE had a different policy regarding brain death, Tanya Roman, a spokesperson for the agency in the Pacific Northwest, said: “Due to an ongoing investigation, I am unable to provide any information at this time.”

Amar’s family said he was disconnected from life support without their consent, although St. Joseph’s Hospital had warned his parents of the medical team’s intentions several days after he had been pronounced brain dead. In Washington state, once a person has been declared brain dead, a family's permission is not required to withdraw physiological support.

“His will couldn’t be so easily broken.”

Over the course of several months, Crosscut spoke to members of Amar’s family with the help of a Russian interpreter. They painted a picture of a man who was restless and eager to travel. He was deeply spiritual and fiercely independent. He also had been the victim of discrimination.

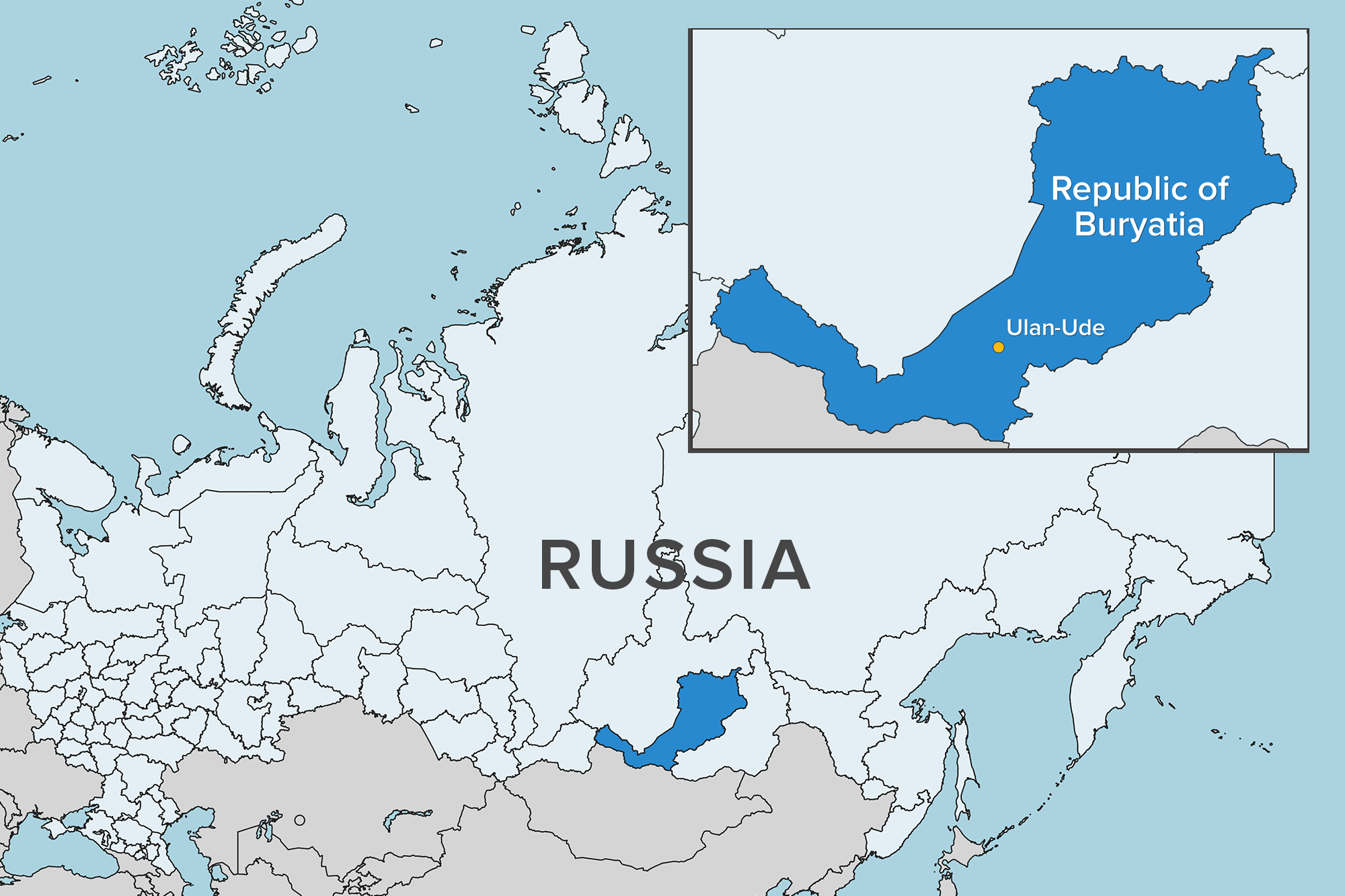

Speaking from the Republic of Buryatia, Amar’s sister, who asked to remain anonymous, said she hadn’t spoken to her brother for some time, but knew he had left for America. Amar had lived in other parts of the world — South Korea, Moscow, Japan — so when he left for the United States, it didn’t strike anyone as strange, she said.

Amar’s former partner, Inna, who asked that Crosscut only use her first name, said one of the reasons he had traveled so much was because of his work as a driver and mechanic, trades he took up after graduating from East Siberian State Technological University. The time he had spent working away from home contributed to their breakup, she said, noting that they continued to share custody of a daughter, who was 6 years old when Amar died.

Inna called her former partner “Mergen,” but said he had been given a different name at birth: Maxim Zhamsaranov. He officially changed his name to “Mergensana Amar” in part to honor his Mongolian heritage. In Mongolian, Mergen means someone who is skilled at archery. Another reason for the change was religious. Amar practiced shamanism, a religion common in the remote Siberian republic, located just north of Mongolia. The religion focuses on interacting with the spirit world. “I am a shaman,” Amar declared during his asylum hearing in August.

His sister described Amar as goal oriented and someone who “loved life” — not anyone she would have ever suspected would contemplate suicide. “His will couldn’t be so easily broken,” Inna said. “He just depended on himself. He didn’t depend on anyone else.”

Amar sought asylum in the United States in December 2017. After flying from France to Mexico, he turned himself in at San Ysidro, a border crossing that sits between Tijuana, Mexico, and San Diego.

According to documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, first reported on by The Seattle Times, Amar told border officials that he had traveled to America because of its reputation as a country that defended human rights, and also because he was in search of financial opportunities.

Amar also intended to take up military training in the states, developing skills he believed he could use to topple the Russian government. “I would love to overthrow the Russian government, but I don’t have the resources,” he told immigration officials during his initial interview. “I wanted to add that I am willing to cooperate with the U.S. against Russia in regards to any matters.” Amar said he planned to stay with a Buryat friend in New Jersey, but ended up at the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma instead.

Part of Amar’s interest in the defense of human rights can be explained through his experience with discrimination. “I have an Asian face,” he said during his asylum hearing, attempting to explain to a judge why he would stand out in Russia. In 2015, he told immigration officials that he was riding a train to Moscow when he ran into six or seven nationalist skinheads wearing masks. They called him a “churka,” a derogatory term for non-Russians. They hit him with bats until he fell on the floor and then started kicking him. Amar was left with bruises all over his body and an injury to his left eye that was severe enough to require surgery.

According to his asylum documents, Amar also was imprisoned for demonstrating for the independence of Buryatia, which has been under Russian rule since the 17th century.

The following year, in 2016, Amar had taken part in a small protest and was arrested. He said he spent a month in jail. Officials beat him and about 30 fellow protesters with sacks of soil and a bat, then tied them to the ceiling in what he referred to as a bird position: handcuffed and pulled up with a wheel and rope attached to the ceiling. As a result, the middle finger on his right hand was dislocated. “It hurt a lot,” he said during his asylum hearing. “We yelled loudly.”

Both Amar’s sister and Inna, his former partner, say they were never aware of Amar’s involvement in any fringe nationalist movements. Inna, however, said she had heard about the skinhead attacks.

Those of Asian descent are known to be victims of prejudice in Russia. According to the SOVA Center for Information and Analysis, at least 71 people in Russia were victims of violence motivated by racist or neo-Nazi-ideology in 2017. People perceived by their attackers as “ethnic outsiders” constituted the largest group of victims, particularly migrants from Central Asia.

There is “a lot of racism against Buryats. Buryats look Asian,” said Elise Giuliano, a lecturer at Columbia University. Some see “them as the other because of how they look.” Buryats, Giuliano said, live in one of the poorest of Russia’s regions, but tend to be well educated, though not necessarily political. As developers have eyed the region, money has poured in and tensions have surfaced, particularly with environmentalists, she said. (In an interview with Crosscut conducted a month before his death, Amar spoke about his concerns over Lake Baikal, listed by UNESCO as a world heritage site. Amar said he was concerned about the pollution the Russian government had allowed to fester at the lake.)

Speaking of Amar’s asylum claims, Scott Radnitz, director of Ellison Center for Russian, East European, and Central Asian Studies at the University of Washington, said the story he told immigration officials “sounds credible.” Although the Republic of Buryatia has never had a strong nationalist movement, unlike, say, Chechnya, even a small circle of activists could lead to unpleasant consequences, Radnitz said.

Melissa Chakars, a professor at St. Joseph’s University in Philadelphia who specializes in Russian Siberia, said that after the Soviet Union fell apart in 1991 territories initially had greater autonomy, until President Vladimir Putin came to power in 2000.

Amar is not the sole asylum seeker from the Republic of Buryatia. Bulat Shagzhin, one of Amar’s countrymen, was an asylum seeker who lived in Pennsylvania, having first arrived in 2016. He told Crosscut he knows of hundreds of others from the country who are also seeking asylum. Shagzhin said that when others in the community heard about Amar, many began to fear for their own life.

“Everyone is afraid because back in Russia this is considered a criminal matter,” Shagzhin said, referring to anyone involved in a separatist movement or a push for autonomy there.

Shagzhin said he got himself into trouble by forming an organization that focused on reviving the Buryat language, which is close to extinction. The organization also published books that included 17th and 18th century Russian history and its complicated relationship with Mongolia. He said the Russian government began to see his group as a threat, forcing him to flee. Shagzhin said he had also been attacked by skinheads while living in Moscow, echoing the concerns about returning home that Amar expressed to U.S. immigration officials. Shagzhin now lives in Europe.

Ultimately, Amar’s asylum claim was denied because, according to the immigration judge, he did not prove that he was a victim of persecution. There was also a small discrepancy between what he had told border officials and the judge regarding whether he had ever been forced to sign a form after serving time in jail. On August 7, 2018, the judge ordered him deported in November.

Rules for gaining asylum have become more strict under the current presidential administration. Last year, for example, former Attorney General Jeff Sessions issued a ruling that makes it more difficult for victims of domestic and gang violence to gain asylum.

But even before Sessions announced the changes, the chances of gaining asylum were low. In 2017, according to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, or TRAC, at Syracuse University, 30,179 asylum cases were decided by judges — the largest number since 2005. More than half, however — 61.8 percent of applicants — were denied asylum status.

“The guards assumed that I wanted to hang myself.”

Soon after his asylum application was denied, according to court documents, Amar began his hunger strike in protest of his impending deportation. It was then that his condition began to decline. He experienced “dizziness and extreme weakness with movement, such as walking to the toilet,” court documents say. He also complained of body aches.

“Amar spends most of his time lying flat in bed, and he has not gotten out of bed to take a shower,” wrote Dr. Sheri W. Malakhova, clinical director at the Northwest Detention Center. “Based on these events, it is my opinion Amar is in imminent danger of going into renal failure ... or becoming comatose due to dehydration and hypotension. Either of these conditions could also lead to his imminent death.”

The court documents also make clear that Amar did not “have any known psychiatric conditions that would cause him not to eat. He has stated that the purpose of his hunger strike is [to] obtain release from custody.”

Documents show Tim A. Petrie, a supervisory detention and deportation officer, expressed concern about how Amar’s possible death would reflect poorly not only on the medical care provided by the detention center staff, but how it might also encourage others to launch hunger strikes, or worse, attempt suicide. Amar could also impact other operations at the detention center, he said.

“Perceptions may be formed by the detained population that the detention and removal staff simply let the detainee die, without doing anything to save them, which could lead to acts of detainee violence and disruptions,” Petrie wrote, according to court documents.

“I am concerned that food strikes or other disruptive or violent acts would be directed at staff or against government property, in order to express the detainee[’s] anger, resentment, and frustrations,” he added.

“Tensions between detainees and staff would be heightened, making almost all aspects of the detention operation more difficult and potentially dangerous for staff to perform.”

Amar had until Sept. 6 to appeal the judge’s deportation order. That same day, ICE obtained an order for involuntary hydration and medical treatment. Amar had been on a hunger strike for weeks by then and missed the deadline to appeal the judge’s deportation order, submitting his application on Oct. 1. In his appeal, Amar explained he had missed the deadline because he had been in medical isolation and lacked access to the law library. The Board of Immigration Appeals called his application “untimely.”

Weeks later, on Oct. 26, Amar was briefly placed on suicide watch, according to ICE's detainee death report. Officials had found a “long hand-made rope made of bedding hidden” in his room. "This was suspected as a possible suicidal gesture," the report says.

In a note provided to activists on Nov. 3, Amar seemed to confirm the incident: “The guards assumed that I wanted to hang myself. Then they took me to a different section for suicidal inmates, and locked me up in a solitary cell, after taking off all of my clothes,” he wrote.

Yet two days later, on Nov. 5, ICE's behavioral health provider determined Amar was at "low risk for suicide," according to the agency's detainee death report.

Sarah Leyrer, a volunteer attorney with La Resistencia, visited Amar several times, including days before his death.

“I found the note rather ambiguous,” she said. “He just seemed down every time I talked to him.”

Inna, his former partner, also spoke to Amar periodically while he was in detention. The last time he called her from the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma was Nov. 9, she said. Inna thought Amar sounded fine. He died about a week later.

On Friday, Jan. 11, with Amar’s ashes finally home, his family gathered for his funeral. It had been approximately two months since he had hung himself, alone, in his cell.

The story has been updated to correct the location of where Bulat Shagzhin is now living.