Khalilzad’s assignment is intended to be a final step of what has become an extended drawdown, initiated in 2014 by then-President Barack Obama, who announced the conclusion of Operation Enduring Freedom. Yet, even as Khalilzad has been talking peace with the Taliban, Americans continue to fight in Afghanistan.

Among them is the elite 2nd Ranger Battalion, based out of Joint Base Lewis-McChord (JBLM), south of Seattle. On its most recent deployment, the battalion lost two soldiers — Sgt. Leandro Jasso and Sgt. Cameron Meddock. Jasso, who died in October, was born and raised in Leavenworth, Washington, and enlisted in 2012. Meddock, a Texas native, was on his second deployment to Afghanistan and died in a hospital bed in Germany after being mortally wounded in a firefight in January.

The Rangers returned to JBLM in February, and current and former members of the unit told Crosscut that the deployment had been defined by intense firefights and relentless hunts for senior enemy leaders.

Watching peace talks is strange for some soldiers who served in Afghanistan. “If that’s the way we’re gonna get out, I guess that’s the way we’re gonna get out,” says Nate Schnittger, a veteran of the 2nd Ranger Battalion. He was a freshman in high school on 9/11. He enlisted in 2005 and became an elite Army Ranger in 2009. Since then, he has been deployed to Afghanistan 10 times.

There are many others like Schnittger who have served at JBLM. The base is home to the U.S. Army’s I Corps, which oversees almost all Army troops on the West Coast and helps make Washington one of the country’s most important hubs of military operations. Troops deploying from the Evergreen State have often played defining roles in the history of America’s longest war. The story of the victories and losses of the Afghan war experienced by the community in and around the base over the past 18 years is a story of the war itself.

The forgotten war

The U.S. military launched Operation Enduring Freedom a little over a month after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, sending forces to Afghanistan to capture the Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden. It was months before America lost its first service member to enemy fire in the country. His name was Nate Chapman, and he was a Green Beret serving with the elite 1st Special Forces Group, based at JBLM.

At the time he was on a special assignment with a small detachment from the CIA’s Special Activities Division called Team Hotel. They were trying to build relationships with Pashtun tribal militias in Pakistan and Afghanistan, as they hunted for bin Laden. Chapman died on Jan. 4, 2002, after being mortally wounded in an ambush while checking on reports of al-Qaeda activity with a group of Afghan militiamen.

Retired Green Beret Scott Satterlee, another member of the 1st Special Forces Group assigned to Team Hotel, was with Chapman when he died. “Things really got real at that point. It’s still not really easy to talk about,” Satterlee told Crosscut.

Satterlee’s memories of Afghanistan are of a grueling deployment in which he had to deal with tribal leaders who, he said, often had dueling agendas. After Chapman’s death, Satterlee trusted few Afghans. He admits that for a time he viewed most of them with a contempt that bordered on hatred, but ultimately in his own way came to admire both the country’s people and its rugged landscape.

In particular, he formed a close bond with a young Pashtun gunfighter named Marouf after providing life-saving medical care to the Afghan’s ailing father. “From then on he wouldn’t let me go anywhere without him,” Satterlee says. “In his eyes he owed me a debt, and he’d die to repay it.” He says that Marouf saved his life several times he was aware of, and probably other times that he wasn’t.

Satterlee, who grew up in Western Washington where he regularly hiked and hunted, says that some of Afghanistan’s mountainous regions reminded him of the Cascades and the Pacific Northwest. Working with local fighters, Team Hotel combed trails and mountains, hunting for al-Qaeda operatives. They traversed rocky roads in pickup trucks and lived in mud compounds like the locals.

But eventually the hunt for bin Laden gave way to a nation-building effort that focused on ambitious infrastructure projects and deployments of large-scale conventional troops to fight the Taliban.

By early 2003, the U.S. military and the State Department were already redirecting resources to Iraq at the White House’s direction to topple the regime of Saddam Hussein and shut down his alleged development of weapons of mass destruction (WMD). U.S. troops found no active WMD program, but they quickly found themselves entangled in a bloody civil war that gripped America's attention for the better part of a decade — Afghanistan became an afterthought.

But even as the battles in Iraq began stealing the spotlight from Afghanistan, the war raged on. In 2004 football player turned Army Ranger Pat Tillman died in a controversial friendly-fire incident in Afghanistan’s Khost province. Tillman famously walked out on a lucrative NFL contract to join the military after 9/11 and along with his athlete brother, Kevin, was assigned to the 2nd Ranger Battalion, out of JBLM.

Today a framed picture of Tillman and fellow soldiers in Afghanistan hangs above the beer taps at The Swiss, a bar in Tacoma frequented by soldiers and veterans. In the picture, which is surrounded by whiskey bottles, the Rangers hold a cardboard sign: “We’d rather be at The Swiss.” The bar sits across the street from the University of Washington’s Tacoma campus and attracts a steady stream of students during happy hours.

“They have absolutely no idea who that is,” head bartender Monkey Willyerd says of the students while motioning to the picture. “That’s why we keep it up.”

Willyerd is not a veteran, but he has worked at the bar for 17 years and has become close friends with many service members who drink there. Some Rangers muse that Willyerd has probably lost more friends to America’s post-9/11 wars than even some veterans. Willyerd says he often feels a sense of alienation when he tries to talk to fellow civilians about it. “I lose people when I start talking about it,” he says. “Nobody wants to hear about that. You just kind of suffer in silence.”

Schnittger, the veteran of the 2nd Ranger Battalion, says that while he thinks most Americans are aware of the war in Afghanistan, they seem increasingly disconnected: “Like, I know who Kylie Jenner is, but I don’t care. So I don’t follow that and I don’t have any interest in that. So it could be that [civilians] just don’t have an interest in [Afghanistan] and can just sort of say ‘I don’t know these people’ for the most part.”

Less than one percent of Americans have served in America’s post-9/11 conflicts, a result of the nation’s transition to an all-volunteer force following the Vietnam War. A historically low number of Americans personally know someone currently in the military — or who has ever been. Increasingly, intergenerational military families fill the ranks of the military — leading to service members becoming increasingly cloistered in communities around military installations and fewer Americans forming meaningful relationships with them.

“You’ve met these guys,” says Willyerd. “One of them has probably held the door open for you. But then we lose someone and no one even notices.”

During a speech at Duke University in 2010 then-Secretary of Defense Robert Gates voiced his worry that the average American believes military service “no matter how laudable, has become something for other people to do.” Researchers at Harvard have found that Americans have a consistently declining interest in military service. According to 2018 data from the Harvard Public Opinion project, 80 percent of Americans between 18 and 29 reported they would “probably not” or “definitely not” join the military.

“People aren't engaged,” says Matthew Griffin, a retired officer who served with the 2nd Ranger Battalion and now lives in Issaquah. “Unless you're directly tied to a deployed military service member, there is no overt awareness of the war. … [It’s] generally not on the radar for everyday Washingtonians.”

Heroes and villains, hearts and minds

In 2007, as Gen. David Petraeus’ “Troop Surge” began to yield seeming success in Iraq, combat was ramping up in Afghanistan.

In 2008, as members of the 2nd Ranger Battalion hunted a senior Taliban leader, Master Sgt. Leroy Petry received gunshot wounds to both legs but continued leading his troops. When a Taliban grenade landed near his men, Petry grabbed it to toss it away. It exploded, obliterating his hand. But Petry survived and received a robotic prosthetic hand that would allow him to remain on active duty and even continue deploying until retiring in 2014 to live in Western Washington.

Petry also received a Medal of Honor, the highest honor for an individual service member. It was one of several awarded to military members with Washington ties.

Staff Sgt. Ty Carter of Spokane was the recipient of another. He received the award while serving at JBLM with the 2nd Infantry Division’s 2nd Stryker Brigade for his actions during an Afghan deployment in 2009 with the Colorado-based 4th Infantry Division. He would go on to deploy again from JBLM and has been active in Puget Sound’s veterans community.

Seattle University alum William Swenson received the Medal of Honor for actions during a fierce battle in 2009 as well, but it was a long road to receiving the recognition. After the battle he harshly criticized the way American commanders handled the battle and was forced into what he called an “early retirement.” When he finally received the award in 2013, he was living in Seattle and unemployed — he requested to return to active duty. The Army granted his request and posted him at JBLM as a plans officer at I Corps. Now a major, he remains on active duty.

By 2009, President Obama selected Gen. Stanley McChrystal — who had commanded the 2nd Ranger Battalion in the early ’90s and went on to lead Joint Special Operations Command — to change the military’s approach to the war. American commanders were hoping to replicate the success of the “surge” strategy in Iraq by sending thousands of U.S. troops into southern Afghan provinces, the heartland of the Taliban. Winning “hearts and minds” and protecting Afghan civilians were supposed to be key pillars of the new mission.

But as the American effort ramped up, JBLM would become a center of negative media attention as the base was associated with some of the long conflict’s most high-profile war crimes.

In 2010 the Army began investigating a dozen soldiers from the JBLM-based 2nd Infantry Division’s 5th Stryker Brigade for potential war crimes. The unit had already gained some notoriety after several soldiers in the unit complained to Army Times reporter Sean Naylor that the brigade’s commander, Col. Harry Tunnell, was giving orders that ran contrary to McChrystal’s counterinsurgency strategy — instead favoring a “counterguerrilla” strategy that emphasized killing enemies over protecting civilians.

"We have done absolutely nothing as a company to improve the quality of life for the average Afghan living in the central Arghandab Valley. What we're doing is not working, and we need to go on a different tack,” one soldier told Naylor. “[That’s] basic counterinsurgency — give them a better option than Islamic extremism."

Soon after the brigade returned home, stories emerged of “thrill killings” of Afghan civilians, trophy-taking and dismemberment of bodies. The Army ultimately charged five members of a self-described “kill team” that prosecutors said were led by Staff Sgt. Calvin Gibbs for the murders of three Afghan civilians. The case became the subject of an award-winning 2013 documentary called The Kill Team.

An Army investigation found broader lapses in discipline across the brigade that many soldiers attributed to Col. Tunnell’s leadership, and painted a picture of a man obsessed with payback after being wounded during a deployment in Iraq. A witness told investigators that Tunnell himself had used the term “kill team” to encourage troops to be aggressive, urging them to seek out "targets of opportunity." One soldier told investigators “if I were to paraphrase the speech and my impressions about the speech in a single sentence, the phrase would be: 'Let's kill those motherfuckers.' "

Though the investigation noted that Tunnell was likely not criminally liable for the kill team’s crimes, it did find him unsuitable for senior leadership. As a result of the investigation Lt. Gen. Curtis M. Scaparrotti, then-commander of I Corps, wrote Tunnell an official letter of admonition that other commanders widely considered the death knell for his career.

Then, as the conflict approached its decade anniversary, it reached an apparent turning point.

On May 2, 2011, President Obama gave a live address announcing that elite Navy SEALs had killed Osama bin Laden in a secretive raid in Pakistan. It was a major political win for his administration. But with bin Laden dead, it also meant renewed questions about why thousands of American troops remained in Afghanistan. The target of the invasion was now dead. And he wasn’t even in Afghanistan. So why were U.S. troops continuing to spar with tribal fighters in the country’s remote rural corners?

Those questions were intensified by the actions of Staff Sgt. Robert Bales. In the early hours of March 11, 2012, Bales wandered off his base in Kandahar Province’s Panjwai District. He murdered 16 Afghan civilians and wounded six others. When he returned to base covered in blood and wearing a blanket like a cape, his horrified comrades promptly detained him. He had singlehandedly perpetrated the worst war crime by a member of coalition forces during the Afghan conflict.

Bales had been on an unusual assignment. His battalion had been detached from the rest of its JBLM-based Stryker Brigade and lent out to Special Operations teams to provide extra security for their bases, in theory allowing Green Berets to spend more time conducting village stability operations — training local fighters, meeting with local leaders and building trust with Afghan communities.

Bales was handpicked to lead a group of 19 JBLM infantrymen supporting a 10-man team of Green Berets at a remote outpost with little supervision. Breaking up a regular infantry unit to lend out to Special Operations troops was not common practice. An Army investigation later found that the JBLM battalion hadn't received proper training or time to prepare for its unconventional assignment — they learned of it just three months before it began and had to rush through training.

While commanders were shocked that a man once considered a star soldier would wander off base, the enlisted soldiers he supervised described him to investigators as an unhinged racist who was routinely abusive to his subordinates, beat up a local Afghan contractor, drank heavily and bragged about using steroids in the days leading up to the massacre. Bales constantly complained that the Green Berets weren't aggressive enough and that he knew better how to win the war. He fumed that they should be focusing on killing Taliban instead of having tea with Afghans.

During Bales’ trial, Army prosecutors flew Afghan survivors of the massacre to Puget Sound so they could testify against him. In August 2013, a military jury at JBLM sentenced Bales to life without parole. Last year his lawyers told reporters they were exploring the possibility of lobbying President Trump for clemency.

The same year as Bales’ bloody rampage, Griffin, who had left the 2nd Ranger Battalion disillusioned with the war on terror, found himself returning to Afghanistan with an unexpected new mission as a civilian. He and fellow Ranger veteran Donald Lee had started a business called Combat Flip Flops that would make its footwear in war zones in hopes of bringing employment and opportunity, while giving a share of the profits to charities that help those communities.

In Afghanistan, Combat Flip Flops works closely with Afghan businesswoman and philanthropist Hassina Sherjan. She moved with her family to Seattle after the Soviet invasion of her country and got her education in America, but returned to Afghanistan to run clandestine schools for girls before U.S. forces ousted the Taliban from power. Under Afghanistan’s new leadership, she was able to move her philanthropy into the open. She’s now involved in several business ventures in Afghanistan, including a textile factory that employs both men and women, which Combat Flip Flops contracts to make scarves and other accessories. Sherjan also runs the charity Aid Afghanistan for Education — which Combat Flip Flops donates profits to generously.

Griffin has called his approach “business instead of bullets” and hopes that collaborative business ventures and cultural exchange can bring an end to the cycle of violence. “Afghanistan is one of the most beautiful places on the planet,” Griffin tells Crosscut. “The mountain ranges, valleys, rivers are truly spectacular. If northern Afghanistan was in the United States, it would likely be a national park. I wish Americans and the international community saw it as a place of beauty, history, and opportunity.”

A long goodbye

U.S. combat operations appeared to be winding down in the summer 2013 as troops with 2nd Infantry Division’s 4th Stryker Brigade turned bases in Kandahar over to Afghan forces and flew back to JBLM. Throughout its deployment the brigade dealt with sporadic firefights and bomb attacks while trying to win over distrustful locals and protect friendly Afghan villagers and leaders from Taliban reprisals — often with uneven success.

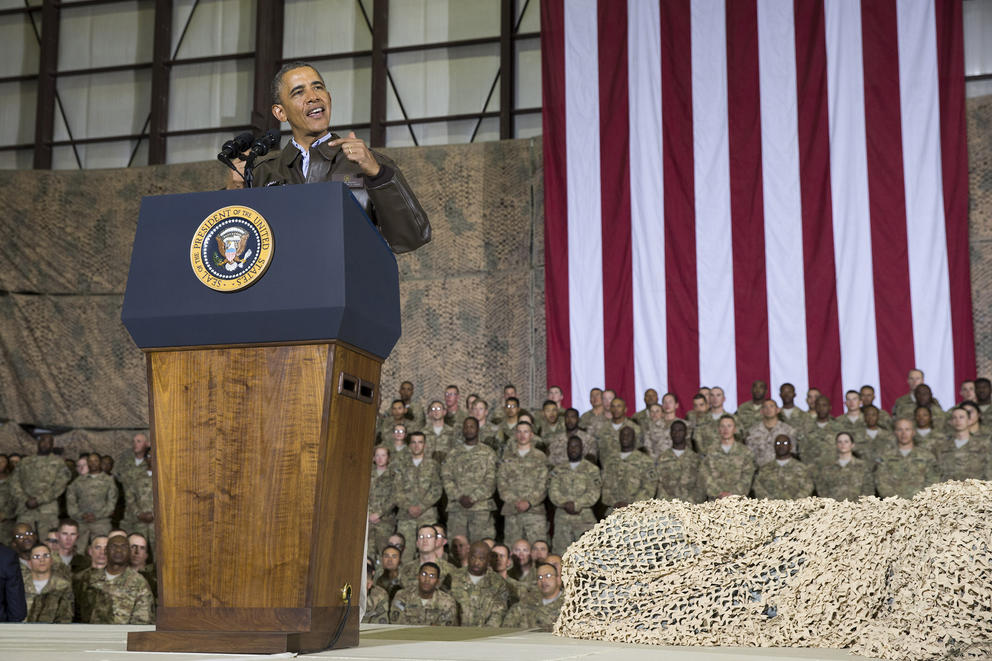

When President Obama officially announced the end of combat operations in December 2014, he said a small force would stay behind to advise Afghan forces, but would gradually shrink until troops left altogether. In a released statement, Obama said “our combat mission in Afghanistan is ending, and the longest war in American history is coming to a responsible conclusion.”

Yet, the conclusion was not soon in coming. By Spring 2015, the JBLM-based 7th Infantry Division — which had been reconstituted as a “nondeployable” headquarters unit to oversee stateside training operations — was deploying to Kandahar Air Field to manage U.S. operations in the country under Operation Resolute Support — the successor to Operation Enduring Freedom. Obama’s withdrawal timeline quickly slowed and within a year was all but abandoned.

Since the official end-of-combat operations, five troops from Washington-based units have died fighting in Afghanistan, mostly members of elite special operations units. “Most people, I think, don’t even realize we’re still fighting,” says Willyerd, the bartender at the Swiss. “Or how we’re fighting.”

Thousands of American troops remain in the country. Many American veterans, struggling to reintegrate into the civilian world and lured by the draw of a return to more adventurous life, have also returned to Afghanistan as private military contractors. In fact, military contractors currently outnumber uniformed U.S. troops in Afghanistan by a wide margin.

The war has fallen into a routine of sorts. During the winter, Taliban militants lay low and resupply near the Afghan-Pakistani border, leading to lower tempo fighting. When the snow thaws in the spring, “fighting season” begins and the intense gun battles resume between the Taliban and U.S.-backed Afghan forces.

U.S. forces frequently join in, often calling air support to help Afghan troops retake towns and cities. Then the snow returns and the cycle restarts.

“We've made great strides as a nation over the past 238 years, but it doesn't mean we can beat history,” says Griffin. “Afghanistan is the Graveyard of Empires. It has defeated the greatest armies in the history of this planet. … To think we could prove history wrong from across an ocean was prideful. Our country should look at Afghanistan as a check to our pride.”

Schnittger, the veteran of the 2nd Ranger Battalion, has a different perspective. He says that while his repeated deployments have been sobering, he “never lost faith” in what he was doing.

“I kind of look at it as I’m in the military and I signed up for it, to do my job.” he explains. “The higher-ups have decided this is our mission and this is what we’re going to do, and I’m going to do my part to the fullest extent that I have to make sure it’s executed properly. The political part of it, the ‘why we’re there,’ I just try to put that in the back of my head to an ‘I’m not going to openly talk about it’ kind of thing. … We executed our jobs to the best of our ability and accomplished the missions we were given.”

Endings and new beginnings

Schnittger was commissioned as a lieutenant on Friday and graduated from Pacific Lutheran University on Saturday. After another round of training, he will serve at Fort Lee, Virginia, as a quartermaster. He started college as an ROTC cadet in 2017, just months after returning from his last deployment to Afghanistan with the 2nd Ranger Battalion. “I’ve actually grown a lot from going to college and it’s definitely changed my thoughts on what the ‘typical’ college person is like,” he says.

Schnittger said that he tended to soften how he talked around his classmates. “I curse a lot and I’m very blunt and I grew up obviously in the military where talking about someone getting blown up or shot is not an abnormal thing, but in school that will get you in trouble and offend people, so I decided to stay quiet for the first few months.” However, he noted that he was much less guarded around fellow cadets as he tried to prepare them for life in the military.

He also noted that initially he experienced a significant culture shock when a professor asked him what his preferred gender pronoun was. “I didn’t know about that,” he explains. “I didn’t know anything about all these movements. In the same way that they don’t follow what’s going on in the war, I wasn’t following what was going on back here.”

Of course, the military culture has also undergone changes of since the war began. In 2011 the Obama administration ended the longstanding “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy, allowing gay and lesbian troops to serve openly. And in 2014 the Obama administration ordered senior leaders to open up all combat jobs to women — though the official combat ban hadn’t kept women out of battle in Afghanistan. The military also began allowing transgender service members to serve openly until the Trump administration ordered a ban, which several veterans have vowed to fight in court.

Meanwhile, in Afghanistan, special operations troops from JBLM continue to conduct missions, but priorities are shifting for the conventional units. The U.S. Army’s I Corps and the 7th Infantry Division at JBLM are increasingly refocusing their training on India and the Pacific to meet the Pentagon’s emphasis on countering Chinese aspirations in the region.

Earlier this year, the Army announced it was tapping thousands of troops for short-term deployments to the Pacific and Asia. The U.S. military’s Pacific Command was recently renamed Indo-Pacific Command to reflect the growing security ties and mutual interests between the U.S. and India. American troops from JBLM have gone to India for joint exercises, while Indian troops have trained at JBLM and elsewhere in the Puget Sound area.

However, the interconnected nature of 21st century conflicts might make it difficult to leave Afghanistan in the rear view. Earlier this year tensions in the disputed Kashmir region boiled over into a brief military confrontation between India and Pakistan. The two nuclear-armed countries have longstanding stakes in Afghanistan and, during the standoff, Taliban spokesman Zabiullah Mujahid told Reuters that "the continuation of such conflict will affect the Afghanistan peace process."

Simmering American tensions with Iran — which shares borders with both Iraq and Afghanistan — have also intersected with the Afghan conflict in unexpected ways. Iran’s fundamentalist Shia regime is historically a fierce opponent of the hard-line Sunni Taliban, but in recent years has pursued a pragmatic alliance of sorts with the Taliban as it fights against both American troops and rival ISIS militants. The Iranian government also has forcibly recruited young Afghan refugees to fight in Syria as child soldiers for pro-regime militias against Syrian rebels.

Whether the Taliban peace talks could bring this all to an end is an open question. The talks have received a lot of criticism in Afghanistan, in no small part because the Afghan government is not involved in the talks, and early reports indicate that an agreement is not in the near future.

The talks also have raised the concerns of many Afghan women, who have noted that there are no women involved. Some fear that their strides in education and civil rights could be used as a bargaining chip, and that the Taliban’s oppression of women could return.

Griffin, whose company works closely with Afghan women and donates to girls’ education initiatives in the country, says he’s heard Afghan women voice those concerns. “It is exceptionally frustrating to have made so many strides toward equality and representation over the past two decades, then be discounted in the peace process,” says Griffin. “The women run that country while the men fight. Ignoring their voices will prove to be a huge detriment to the long-term healing of Afghanistan.”

Meanwhile, Americans continue to be directly impacted by the ongoing war, and some are questioning whether their fellow citizens appreciate the real-world consequences. Willyerd admits he’s bitter at what he considers ambivalence on the part of many Washingtonians about a war that’s killed several of his friends. “Whether you believe in it or not, they died for you,” he says. “My friend of 10 years left [behind] his wife — who I know — and his two beautiful daughters.”

Schnittger says that he doesn’t want to tell people what to think, but that he does want them to think — and that America’s increasing apathy to war is unhealthy. “I think it allows decisions to be made without Americans weighing in on it,” says Schnittger. “Whether it’s through your elected officials, if you oppose the war let them know. If you support the war let them know. I’m going to do my job, no matter what happens. Maybe I’ll just only do my job in Fort Lee, Virginia, instead of Afghanistan.”

Part of that job, Schnittger observed, will be leading soldiers born after 9/11. “I never thought it would be that long,” Schnittger says. “It’s weird to know that somebody who went to Afghanistan in 2001 could be deployed with their son or daughter now and that’s not an uncommon thing.”

As Willyerd pours a beer at The Swiss, he notes that some of the children of Rangers he’s known and been friends with for years — kids he saw grow up — are serving at the 2nd Ranger Battalion now just like their dads. It’s something that makes him both proud and anxious. “What do I do when I lose one of my nephews?” he asks.

Retired Green Beret Satterlee recalls that a friend who recently returned from an assignment in Afghanistan told him that his team captured a low-level teenage militant and questioned him. The young militant became confused when asked about 9/11. He told the Americans he didn’t know what the Twin Towers were and had no idea why the Americans had come to his country at all.

“Now we’re fighting the next generation,” says Satterlee. “I feel like that says something about the legacy of this mission, but I’m not sure what.”