When people imagine homeless veterans, their mental image is almost inevitably male. However, as the number of women serving in the military has increased, female veterans have become the fastest growing demographic in America’s homeless community. Just as with male veterans, these service members struggle to transition to civilian life, and some grapple with unemployment and homelessness.

Monique Brown, head of Veteran’s Outreach at Seattle’s El Centro de la Raz, has been working to identify veterans in Seattle’s homeless communities for years, as part of an ambitious King County initiative to eliminate veteran homelessness. But getting accurate numbers on the numbers of homeless women veterans has been a challenge.

“The tough thing about women is that a lot of them don’t self-identify as veterans,” Brown says. “There’s some confusion of the definition of what is considered a veteran, even within the military community.”

Brown served in the U.S. Army for two decades, deploying twice to Iraq as well as to Guantanamo Bay. Even when she returned from her first deployment to Iraq, she didn’t feel like a true veteran, until learning that anyone with two years of service and an honorable discharge qualifies.

Many of the Vietnam and Desert Storm-era female veterans she’s come across often don’t feel comfortable claiming their veteran status. “Women had not been doing so much combat stuff, mostly support roles, so they didn’t think they could claim the title ‘veteran,’” she says.

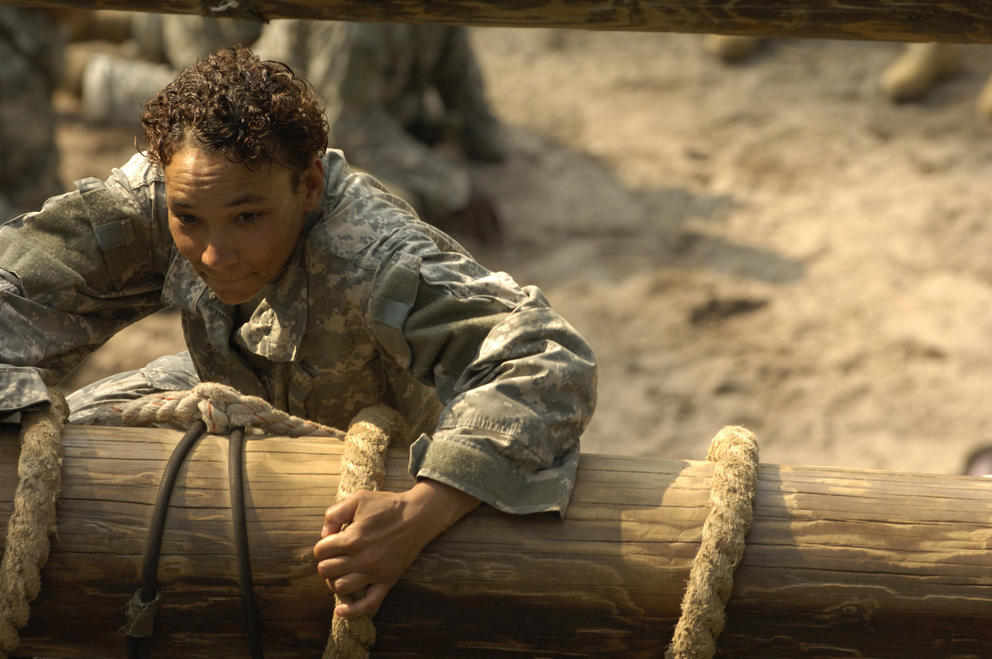

However, that’s changing fast. Female service members in the post-9/11 military are very different from their predecessors in many ways. The military recently opened up all its jobs to women recruits, including infantry and special operations fields. Even before that change, the nature of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan has meant that non-combat soldiers were regularly involved in combat-related situations.

“When we were in Iraq, we got pulled for the female search mission, so you were out there with the guys knocking down doors, climbing walls, getting shot at, the same things,” Brown says. “So I think this post-9/11 group is probably going to identify a little differently than those before, just because the roles have totally switched.”

As more women see combat, more are coming home with the physical and mental scars of battle historically associated with male veterans. Additionally, V.A. statistics report that one in five women veterans respond “yes” when screened for “military sexual trauma” — rape or sexual assault during their service.

However, many women are reluctant to seek help.

“I’ve come across women with mental issues that they might not even aware of,” says Brown, who herself struggled with post-traumatic stress after leaving the military. She’s seen homeless veterans exhibiting signs of depression, schizophrenia and other mental disorders. “I can’t force them to seek treatment.”

Many veterans have reported frustration with the V.A. system. But Brown says women in particular are often hesitant to turn to the V.A., in part because of the way they’re immediately greeted. Staff often assumes women are either spouses or children of veterans, rather than veterans themselves.

“They feel like they’re not even identified at the V.A. hospital as a veteran, they’re always ‘Oh, your husband must be the vet,’ so they don’t utilize the system as much,” Brown explains.

But that response does touch upon an issue that disproportionately impacts homeless women. Many in fact are wives and mothers. Julia Sheridan, the founder of the Seattle-based Outreach and Resource Services For Women Vets, told Crosscut that the public often assumes that homelessness is a problem for individuals rather than families. But it can be particularly stressful on mothers.

It can be particularly challenging for mothers to visit the V.A., as they often need to get a babysitter — appointments are made far in advance and most facilities don’t have space to accommodate children while their parents meet with care providers. For homeless mothers, finding someone they trust to watch their children may be impossible.

“The V.A. has no childcare services to speak of,” Sheridan says.

King County has touted its success in reducing veteran homelessness. “We’ve transformed ending veteran homelessness. And that was done by literally knowing everybody that you want to serve by name,” Bill Block told Crosscut in an interview earlier this year. Block is the former head of the Council to End Homelessness and is currently a consultant for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

“We have also made a much greater effort, beginning last year, to increase our outreach and to work more closely with both the VA and the state Department of Veterans Affairs (WDVA) to create a ‘named’ list of veterans who are homeless and to work more closely with each veteran,” says Sherry Hamilton, a spokesperson for the King County Department of Community and Human Services.

As of August, King County’s list of homeless veterans totals 835 individuals.

“With resources and focused work, we really have shown that we can end veteran homelessness,” says Block. “That shows that if we put those same resources in and work into other populations, we can do that for them also.”

Brown acknowledges that there have been major strides in combating veteran homelessness. However, she cautions against overblowing that progress, as county officials “define homeless as on the street or in a tent city….Now they’ve opened it up a little bit to include shelters, but if you’re in jail — even if you have no where to go when you get out — you are not homeless. If you’re couch surfing because a friend lets you stay, you are not homeless, and they won’t help you.”