“It’s definitely a way to control the ideas,” says Smith-Venturi. “And kind of … make them safe.” Soft-spoken and emanating a surprising sense of levity given her subject matter, she says her boxes are about revealing truths, but with an added benefit: “You don’t have to look at it right now if you don’t want to.”

Smith-Venturi, who is 82, grew up in Michigan and went to art school at the Society of Arts and Crafts (now the College for Creative Studies) in Detroit. Upon graduating, she thought she was a painter. “But I wanted more dimensions, so I was gluing things on the paintings,” she recalls. She was after something more tactile. “Working with a brush, I felt like I wasn’t as in contact with what I wanted to do,” she says. “I found that what I really like is building things with my hands.”

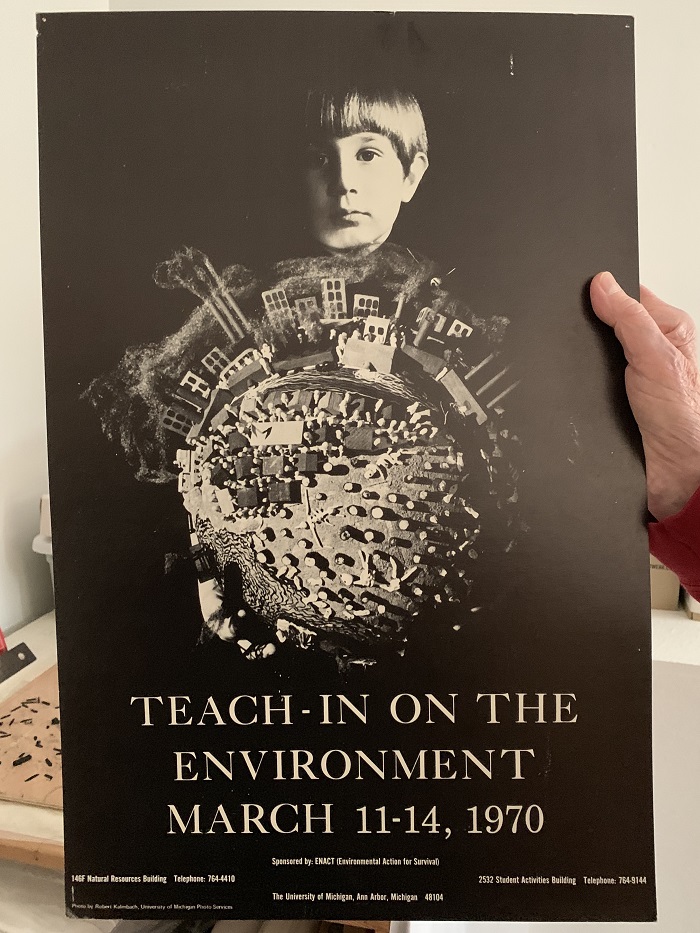

In the early 1970s Smith-Venturi became involved in the environmental movement, and created the poster for the University of Michigan’s first Teach-In on the Environment (part of a national grassroots effort one month before the first Earth Day). She pulls the striking black-and-white poster out from behind a Keen shoebox holding supplies (“faux grasses, bushes and hair”). In the image, a somber young boy (her son) holds a globe she encrusted with three-dimensional landscapes: crowded buildings, a forest of stumps, animal skeletons and factories clouded in a haze of black netting. It foreshadows her current work, and also reflects the potential power of small replicas made from materials a child could use.

Having visited the Pacific Northwest in her younger years, Smith-Venturi felt drawn to the “incredibly beautiful environment.” She moved west in 1989 and landed in a spectacular setting: the Dungeness Spit, where she lived in a cabin and served as a volunteer caretaker until meeting her partner, Pamela Murphy. The two moved into a Craftsman bungalow in Port Townsend, where they’ve lived for 26 years. One wall of the cozy living room is stacked with Smith-Venturi’s completed boxes. The titles stamped on the sides read like a dystopian tone poem: “Extinct,” “Coming Apart,” “Square One,” “Sinking.”

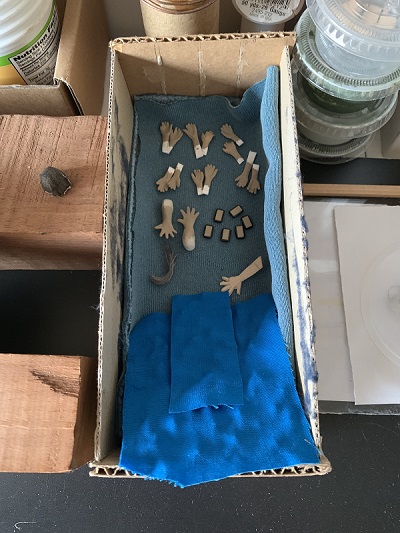

Opening each box requires peeling away several layers. First, lift the lid off the plain wooden box, on which she has stamped the title of the piece with individual letterpress blocks. Next, unwrap the carefully cut and sewn piece of fabric that is swaddled around the inner box and embroidered with the title. Last, unfold the petal-like panels of the center box to reveal the enclosed scene.

“I wanted a sense of intimacy,” Smith-Venturi says. “I like the fact that it takes a personal effort to open them and reveal them.”

Cynthia Sears, who founded the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art, has been instrumental in acquiring Smith-Venturi’s work for the BIMA collection. She considers the boxes part of the “book art” tradition, and is captivated by both the “mind boggling workmanship” and the participatory nature of the work. “I just fell in love with the whole ceremony of opening the box and having this story unfold,” she says, of her first time seeing Smith-Venturi’s pieces. “I felt like I was taking part in a ritual.”

“I chose the form partly because I’ve always been fascinated by boxes, even just empty ones,” Smith-Venturi says. “There’s something about opening a box and revealing what’s inside; there’s a basic fascination.” She started out making larger dollhouselike sculptures with narrow windows that required the viewer to approach and peer inside. Inspired by Japanese book boxes that unfold like origami, she decided to create smaller boxes that could be opened up entirely. “It was Cynthia [Sears] who showed me that the act of revealing is similar to opening and reading a book,” she says.

In the studio, one of her almost-completed boxes, “Phoenix,” lies open on a counter. The scene is a burned out wasteland with gnarled sticks scattered across a blackened ground. A green and gold bird sits in the center — a phoenix doing its best to rise up again. But it appears to be in trouble, with one wing stuck on the ground. “I started this piece last year, inspired by the wildfires,” she says. “I was still working on it when the fires happened again this year. My sister lives in Paradise, California, and was able to get out. But at that point it’s a little too close.”

Another box, “Fit,” is covered in paper that resembles small stones. When opened, it reveals an overgrown graveyard in which the tombstones read “Sapien.” Oversized, wildly colored insects made from Fimo clay and twisted pine needles crawl among the graves. “It concerns survival of the fittest,” Smith-Venturi says. “I’m looking at what might survive in a much warmer climate.” The bright bugs have whimsical appeal, but the humor here is dark.

Asked about her artistic influences, Smith-Venturi says, “Probably Goya.” It isn’t the first name one might expect to hear from a practicing Buddhist wearing a purple fleece vest, fuzzy moccasins and socks dotted with cute raccoons. But a nod to the 18th-19th century Spanish painter of war, mental asylums and Saturn devouring his son makes sense. “He was willing to do all that stuff that nobody wanted to look at,” she says.

Nonetheless, according to BIMA’s Sears, “There is definitely hope in the work.” The museum founder explains, “Her message is often one of a warning — a path we’re going down and we’d better think about turning around. There’s a piece called ‘Urge,’ a dystopian scene, but the concrete is cracked and green things are pushing their way toward the sun. It’s about an unstoppable urge for life, no matter how bleak things might be on the surface.”

“I do have a sense of hope,” Smith-Venturi says, when prompted. “But it’s not as strong as it used to be.” Despite her gentle manner, she is not one to sugarcoat. She concedes, “I think the most hopeful thing is people are becoming more conscious and willing to look at the difficulties.”

Each box takes Smith-Venturi three to four months to construct. She’s made 36 of them in the past 10 years (and keeps track of titles, contents and completion dates on index cards in their own box). And while she balks at hitting a target number, she also has no plans to stop. “I feel like it’s something I have to say,” she says. “So I did them not knowing whether they would ever be shown, but just because I had to do them.”

Back in the studio, she looks out through the horizontal window at the garden, where snowberry bushes are dotted with white fruit. The view reveals a human-scale box — the simple meditation hut Smith-Venturi built with wood lattice sides — a place where she can let go of the worries that crowd her mind. “After making all these boxes,” she says with a smile, “I made one for myself.”

Crosscut arts coverage is made possible with support from Shari D. Behnke.