“The NHL said, ‘Perfection? No. Let’s do 2021,' ” according to a project insider, summarizing the exchange.

So the Los Angeles-based Oak View Group developers, who are investing $800 million — the latest figure confirmed Tuesday, up from the original $650 million — to tart up KeyArena, after consulting with their political partners in city government, came to a conclusion:

After waiting more than 100 years for another shot at repeating the Seattle Metropolitans’ Stanley Cup victory in 1917, what’s one more year?

Because even National Hockey League owners know, based on the experience of their NBA brethren, when it comes to pro sports and Seattle public works, expecting perfection is an impossibility. Best to plan for mayhem, then dig out.

The calendar was bumped to October 2021. Team owners, meeting at a resort in Sea Island, Georgia, voted 31-0 Tuesday to make Seattle their 32nd franchise, a milestone event in a sordid civic saga.

The marketplace was the largest in North America without either the NHL or NBA. All it took to solve for that was $1.45 billion — the arena cost, plus the expansion franchise fee of $650 million, $100 million of which was paid Tuesday — and a city government willing to say yes to free private money to fix a public building in a public park.

In a word, it is astonishing.

The official grant of the franchise Tuesday puts largely to rest about a century of caterwauling, finagling, duplicitousness, mendacity, grandstanding, errors of fact and fiction, temporary successes and abject failures regarding major league hockey — and major league basketball — and Seattle.

A building plan, a league, a team and ownership are all set to light the hockey lamps. NHL Hockey Partners CEO Tod Leiweke, the former Seahawks boss (2002-10), came back to town exactly for this moment.

“Today is a dream come true for an entire city,” Leiweke said after NHL Commissioner Gary Bettman made the announcement in the Georgia resort’s ballroom. “I’m holding in a lot of emotions. But today I think about the fans. I woke up today thinking about the fans and what did they feel on March 1, when they put down season-ticket deposits not knowing anything.”

More than 10,000 online deposits rolled in during the first 12 minutes, 32,000 in 12 hours. They didn’t know anything, but apparently were eager to learn.

Also on a learning curve was Oak View Group’s CEO, Tim Leiweke, Tod’s brother. He learned that appeasing all the stakeholders at Seattle Center and the surrounding urban village, already inundated by newcomers and construction from Seattle’s skyrocketing economy, was going to be difficult and expensive.

Long experienced in pro sports and arena building, Tim Leiweke had never been through The Seattle Process.

“The most complicated project I’ve been involved with,” he said recently. As a result, it is already over budget and no longer on time, and demolition hasn’t even started. The landmark arena roof must be kept in place, the arena floor must be 15 feet lower to accommodate an expanded footprint, the city’s labor contracts must be honored, and the price of steel soared because of tariffs.

On its own, OVG added a $70 million training facility on the grounds of Northgate Mall, which needs to be ready in the summer ahead of when the team begins to train.

OVG planners began talking about needing more time, suggesting perhaps having the team play its first month entirely on the road. That’s when the NHL intervened.

“It was clear that this team wants to start in the absolute best right way,’’ the NHL’s Bettman said. “And the certainty over the construction timeline — or the lack of certainty — led us to believe that making the start of the ’20-21 season would be speculative at best and unlikely at worst. And we all agreed that it was better to get the building done right.’’

According to one hockey source, the date of the opener was less important than affirming the 32nd team’s eventual existence. Player contracts need to be done with an expansion draft in mind, so the iffiness around the Seattle’s building readiness in 2020 — including the potential for myriad problems at a site the builder does not own — prompted a pumping of the brakes.

One potential benefit of delay is avoidance of a potential labor standoff with the players union that could cast a pall over a start in 2020. The current collective bargaining agreement expires after the 2021-22 season, but the NHL can opt out next Sept. 1. The union can do so 18 days later.

The belief at the moment is that the arena will be ready to open for concerts and the WNBA Storm in the spring of 2021, starting the revenue stream that must pay off construction debt over the 39-year length of the lease.

Music fans did not seem to be around Tuesday to cheer the giving of the word.

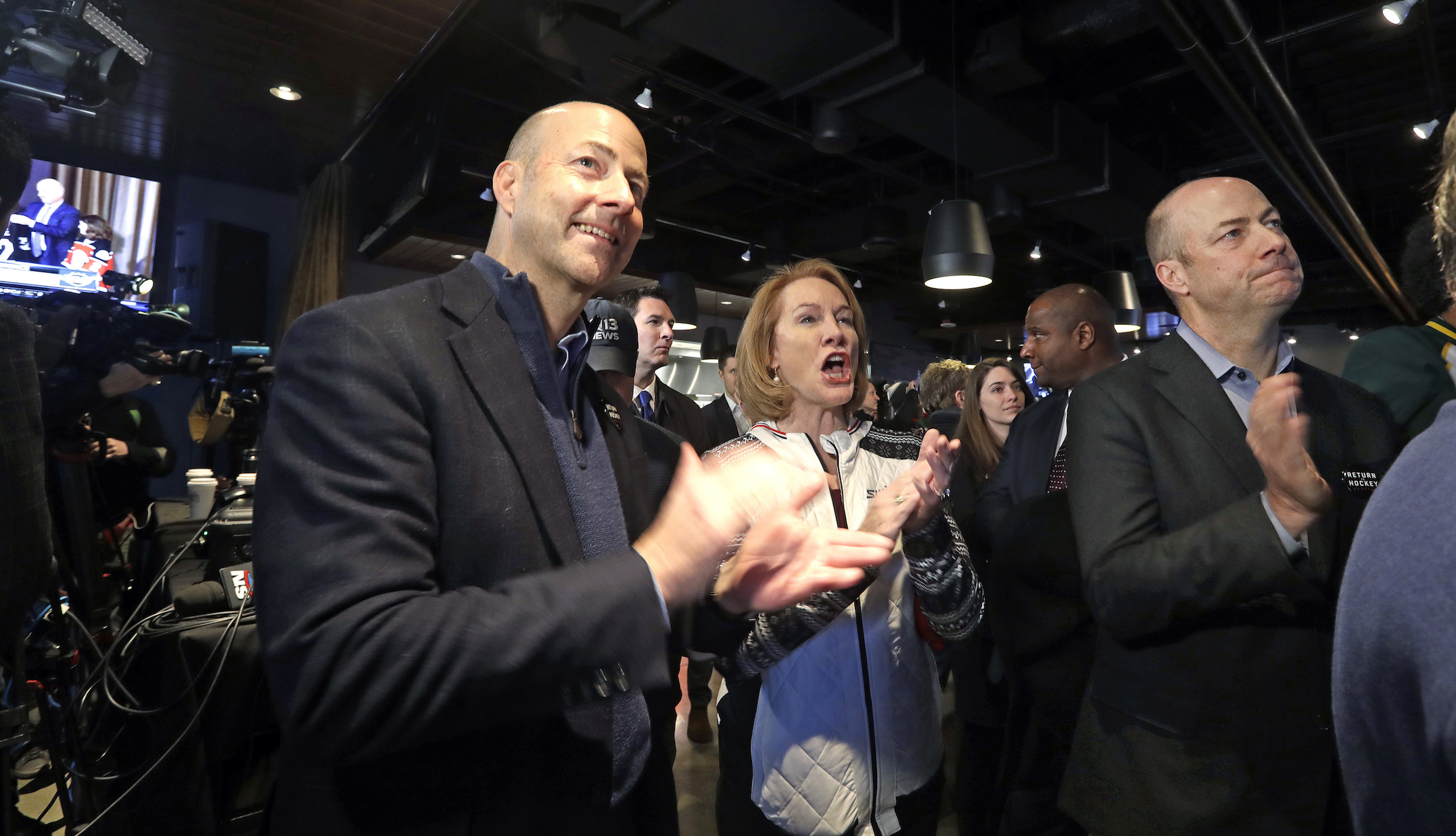

Almost 200 people, many in hockey regalia, jammed into Henry’s Tavern in South Lake Union to watch live the NHL press conference that confirmed what had been a given known since the surprising ticket-deposit largesse in March.

One of the most exuberant fans there was Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan, a big sports fan.

“No city has ever gotten a deal like this,” she said. “The amount (OVG) is paying for the arena, and the expansion fee — they’re invested in Seattle.

“I grew up here and lost two teams, the Pilots and the Sonics," she said. "We’re going to have hockey for my kids and their kids.”

The tradition of municipal extortion by pro sports teams is long, aggravating and persistent. But with 1.45 billion in bucks from the private sector, perhaps the buck stops here.