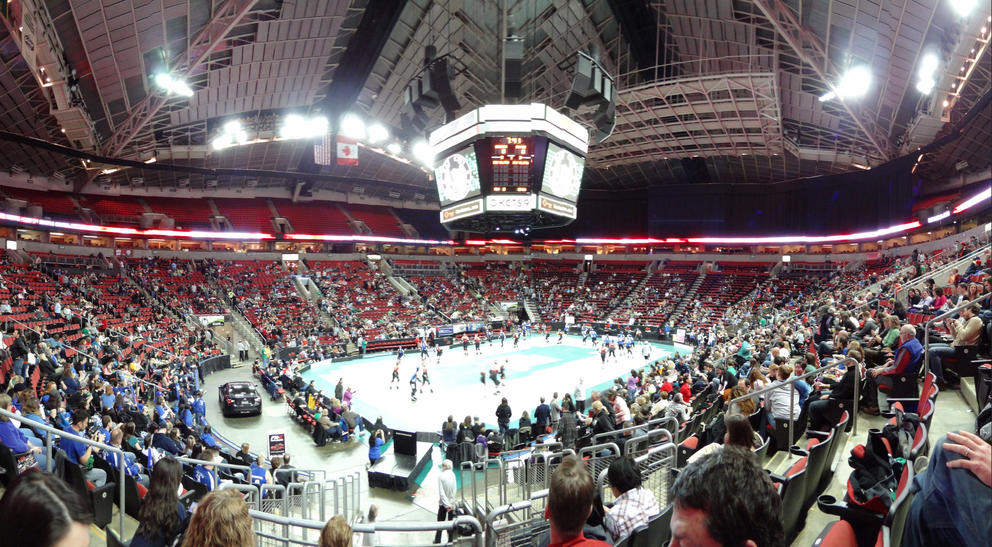

Basketball, hockey fans and taxpayers, should be rejoicing that the effort to get a viable arena in Seattle is back to square one. Namely, that KeyArena at Seattle Center is again in play as a potential professional male sports venue (it’s already home of the WNBA’s Storm).

The city has issued a request for proposals (RFP) to turn the facility into an NBA and NHL-ready space using private funds. At least two major arena developers are planning to submit proposals. In the meantime, developer Chris Hansen is still hoping to move his SoDo arena forward without city financing. So, for the first time we have some genuine competition from multiple players over sites that could bring “the Sonics” back to Seattle, and pro hockey too.

The big question about KeyArena — forget it, I’ll call it by its original name, the Coliseum, since Key Bank no longer sponsors it — is whether an arena acceptable to the NBA and NHL can be built on the site. City officials say they want to see proposals that assume the old Coliseum structure stays in place, but are willing to entertain additional concepts that start from scratch.

The Coliseum is not currently a designated historic landmark. Word is the city is preparing a nomination that will go to the city’s Landmarks Preservation Board within the next couple of months to settle the question. Artifacts Consulting of Tacoma, a well-respected historic preservation firm, is working on the nomination. They conducted a historic landmark survey of Seattle Center in 2013 and found the Coliseum’s to be landmark eligible. If it is designated a landmark, the city council will approve guidelines for what can and cannot be changed.

It is hard to imagine that the Coliseum won’t meet a number of the required criteria. Its distinctive look (that hyperbolic paraboloid roof suggestive of a Salish rain hat) make it a literal recognizable landmark; it’s a highly significant work by architect Paul Thiry, father of Northwest modernism; it is associated with the historic Seattle World’s Fair; and its original cable roof structure was innovative and, though replaced in the mid-1990s, the form of the roof is intact. No one who attended the World’s Fair in 1962 would fail to recognize the Coliseum exterior today.

The interior, which has been remodeled and reconfigured many times, is very unlikely to qualify for landmark protection, which means that it would be possible to build something entirely new under that roof that is consistent with the landmark status and in keeping with the building’s original purpose. Can it be made to work to current NBA and NHL standards? Consultants for the city and some of the potential RFP bidders say they are sure it can be.

If the Coliseum’s exterior was constructed as a permanent fixture, with its massive concrete supports, impressive footprint, and squat pyramidal top, the rest of the facility was designed to be highly adaptable. When the concept was unveiled in the late 1950s, reactions were mixed. Some thought it was “a stunner,” that when “seen from the air … will gleam like a giant gem.” Others said the roof looked like a sculpture hammered out of old gas cans (shades of Frank Gehry’s smashed-looking EMP).

But the builders knew it would survive the fair to live on as a permanent sports and convention center. That was a key element of the plans the public voted for when approving bonds for a civic center at the site. In 1958, Gene Walby, head of a northwest sports advisory committee, discussed the proposed Coliseum with the Seattle Times and said, “By having the proper facilities, the Northwest could well bid for major status in basketball and hockey.” So it’s back to the future.

The Coliseum was designed to be adaptable from a world’s fair pavilion in 1962 (it was Washington State’s) into a permanent home for sports (basketball, hockey and boxing) as well as concerts and conventions. It cost some $4 million to build and nearly $2 million to renovate after the fair. It reopened in 1964, and has since been updated, repaired (it was leaky) and remodeled a number of times to keep up with changing uses, priorities and demands.

Very early in the world’s fair planning, one bold concept was to put a cable suspended roof over the entire fairgrounds — Thiry, the architect, was also the fair’s chief overseeing architect and had been inspired about suspended cable roofs after visiting the 1933-4 Chicago World’s Fair. The idea was ditched, fortunately, but the suspended roof concept was applied to the Coliseum, which became the covering for variable, and even fickle, sports-driven markets.

We have learned that the life span of such venues is short: We blew up the Kingdome before it was paid for; the Coliseum became obsolete for NBA basketball not once but twice. When the Sonics left town, we were told the Coliseum-Key was not suitable for the NBA; now we’re told that smaller, high-amenity arenas are back in vogue.

What we have is a permanent public site and a shelter with lots of flexibility about what happens underneath and adjacent to it. Instead of building from scratch, as at SoDo, why not make use of the existing infrastructure where the pubic investment has already been made? If the public is going to be asked to invest more, let it be in dealing with the transportation and parking that will attend any site.

Geoff Baker, who has been reporting on the arena for The Seattle Times, says many of the arguments that the arena can’t be made to work again are “myths.” That may be so, but as anyone who has listened to decades of sports hype will tell you, it is wise to be skeptical about all claims.

The Coliseum should be landmarked in any honest evaluation of the significance of the structure. That need not be an obstacle, if the consultants and proposers are right. If it can continue its original duty of being a venue for sports and entertainment — and make money for the city in the process — it could be a win for history, sports fans and taxpayers.

Disclosure: Knute Berger has worked as consulting historian for the neighboring Seattle Center landmark, the Space Needle.