Now the community is gambling its future on a young Canadian prospecting company, Adamera Minerals Corp., whose sole project consists of a search for gold on a chunk of land outside Republic.

Holding a gray rectangle of rock, Adamera geologist Braelin Yearsley scrutinized its white streaks with a magnifying glass. He passed the rock and glass to driller Ethan Heinen, who then handed them off to driller Justin Griffin.

Finally, Mark Kolebaba, owner of the Vancouver, B.C.-based company, checked out the sample. The streaks were sulfides, a hint that gold may be near.

“For me, it’s a treasure hunt,” Kolebaba said.

The prospecting ventures that once created prosperity for this region sought out gold near the surface. Adamera will go deeper.

The company set up shop in Ferry County two years ago to prospect the modern way, with magnetometers, electric shocks and detailed, constantly evolving subterranean maps.

“It’s bringing the 21st century to a 19th century art form,” Adamera lab technician Casey Nelson said.

Ferry County’s 7,500 residents have anxiously watched Adamera’s prospecting. The closure of Washington’s sole remaining gold mine, located in neighboring Okanogan County, idled a Republic mill that had served as the town’s largest private employer.

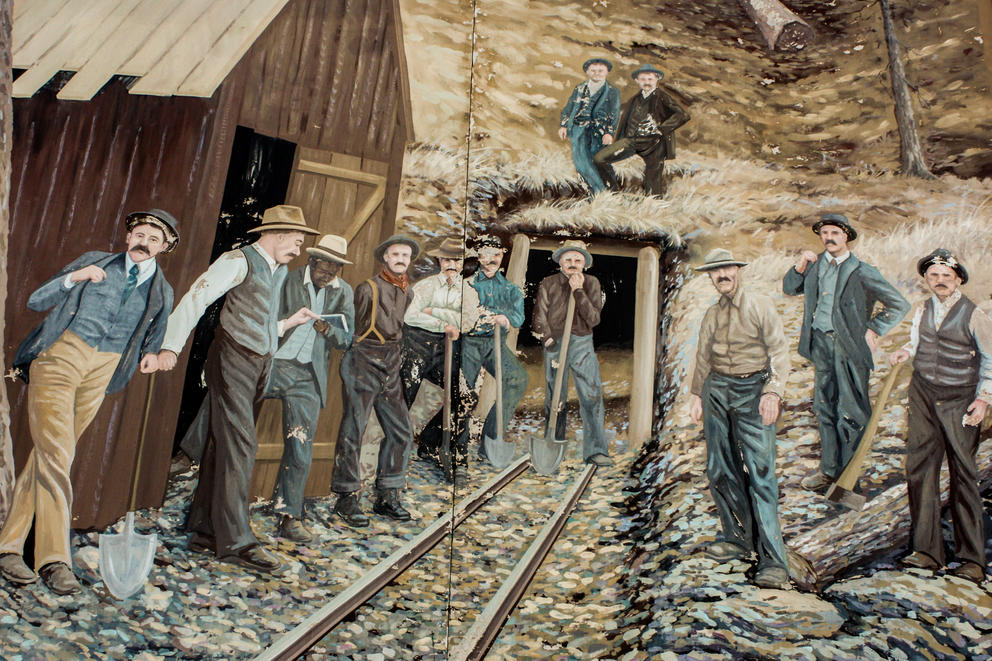

Gold mining is intertwined with Ferry County’s soul and is soaked into its culture. Mining drew settlers to the area and mining, for more than 120 years, kept the county alive.

Republic’s biggest weekend each year is Prospector Days, complete with a parade and a mock robbery. Each year, thievin’ varmints stick up a couple of gold prospectors. And each year, the robbers get gunned down by a posse on Republic’s South Clark Street, the town’s main drag. Tom Johnson is invariably one of those robbers, whose explosives expertise is called on each year to blow up the strong box in front of about 500 downtown spectators.

At 74, Johnson has been around Ferry County’s mining scene for decades and can eyeball the best spots to blast for samples. Lately, though, he has been watching mining fade away and young people steadily leave Ferry County. “I’m sorry to see them go,” he said, his handlebar mustache in full glory. “It changes the character of the area.”

The shootout captures Republic’s Wild West past, but the fate of the community hinges on two questions: Does it have a future in gold mining? Does it have a future without it?

Gold was discovered in the region in 1857 at Rock Creek, just north of the then-newly minted Canadian border. The trails to Rock Creek cut through the Kettle River and Curlew Creek valleys south of the border.

In the early 1890s, surveyors began mapping townships on the Colville Indian Reservation. In 1896, mining claims began to be filed in what is now Ferry County. The first staked out at Eureka Creek, just north of present-day Republic. Sixty-four men made the canvas tents and canvas-topped shacks of Eureka Camp their home, and other miners began streaming in.

The gold rush was on.

Thousands of mining claims were filed in the years that followed. Eureka Camp changed its name to Republic after one of the mining ventures, the Republic Gold Mining & Milling Co.

Mines opened and closed. Companies popped up and died. The price of gold rose and fell.

“It’s always been boom or bust,” said Jesse Eich, an Adamera employee.

Almost 188 tons of gold had been mined in the area before, one by one, the mines quit producing and closed.

The state’s last active gold mine, on nearby Buckhorn Mountain, closed in 2017 after nine years in operation. At least 34 tons of gold had been drawn from that mine, an amount worth approximately $1.3 billion.

Kinross Gold Corp. extracted gold from ore at its mill just northeast of Republic. During most of the Buckhorn mine’s existence, Kinross employed roughly 200 people. In 2015, the company payroll was $27.6 million. Today, a skeleton crew of 27 maintains the mill in hopes of revival.

“Pretty much the entire time I worked for Kinross, I knew it was gonna close,” Heinen said.

Johnson added: “This back-and-forth jockeying has sustained us for some time. I feel sorry it had to close. But we can’t expect them to continue with something not viable as a project.”

While the loss of 200 jobs would barely register in Seattle, it was a huge blow to tiny Ferry County.

“It’s like Boeing, Microsoft and Starbucks in the Seattle area, and they all left at once,” said state Rep. Joel Kretz, R-Wauconda, whose legislative district includes Ferry County.

While the gold mining has stalled, the culture of mining is carried out by those who have worked the mines.

“You’ve not seen dark until you’re underground when the lights are not on,” said Heinen, who worked at the Buckhorn mine. “I miss being underground. I love being underground.”

Working in a gold mine takes lots of skill. It’s dark. There is a lot of technology to master. Some lab work. A bit of geology. In some jobs, a familiarity with explosives. And some applied muscle work.

Ferry County residents say a large number of ex-Buckhorn workers moved to Alaska, Nevada, Montana and other places where gold mining continues. “There’s not that many other jobs to go to” in Ferry County, Nelson said.

Like broad swaths of rural Washington, Ferry County was once sustained by mining, timber and agriculture, which in Ferry County meant cattle ranching. Now all three industries have more or less disappeared.

Severe restrictions limiting logging on federal land created since the early 1990s pushed forestry jobs out of Ferry County, where half of the forests are federal. State records show six sawmills in Ferry County in 1968; there is one today.

Ferry County’s ranching blossomed in the 1970s and 1980s as side ventures for the area’s miners and loggers, often taking place on small pieces of land next to their homes. As forestry and mining jobs vanished, so did the homes with their small ranches, said Curlew rancher Bowe Brown. Only a handful of ranches remain.

Unemployment is unchecked in Ferry County. The unemployment rate in August 2018 was 9.3 percent, the worst in the state. By comparison, the state’ unemployment rate was 4.5 percent; King County’s rate was 3.2 percent.

The county’s median family income in 2015 was $40,340 at a time when the state median was $63,439. Kinross employees averaged more than $80,000 in annual wages, Ferry County leaders said.

Gina Myers, Kinross’ manager in Ferry County, said economic activity related to the operation supported another 230 jobs in the county. State economists expect Ferry County’s job market to remain stagnant.

The “silver bullet” for Ferry County’s woes would be new gold mine. Yet local leaders are pessimistic about the discovery of new gold providing fast relief. Permitting a mine takes years, in part because potential gold veins are under lands controlled by various agencies with separate permitting schemes. Buckhorn was the last project permitted, a process that took the owners 20 years, Myers said.

“Permitting a mine site can be a lengthy process,” Myers said. “However, timelines for permitting mines are very project- and site-specific, depending on scope, complexity, and multiple other factors.”

A company considering investing millions of dollars into mining a gold vein may be scared away by the prospect of waiting years for all the permits, Kretz said.

“That’s what’s killing it — the rate of getting a permit,” the legislator said.

Even if mining resumes, the county faces serious obstacles to economic growth. Ferry County is isolated. Broadband service and cellphone coverage is spotty. Only 17 percent of the county is on private land, constraining the property tax base.

Ferry County does attract hunters and their dollars. But hunting seasons are short and, while picturesque, Ferry County’s isolation dissuades tourists.

“We’re not like Leavenworth, where you’re two hours from Seattle,” said Jim Milner, Republic Chamber of Commerce president. “We’re realistic enough to know we’re off the beaten path.”

“Recreation is not going to replace the quality of the jobs we’ve lost,” said Sen. Shelly Short, R-Addy, whose district includes Ferry County.

Locals are looking to the state government for help that has been slow to come from Olympia.

Gov. Jay Inslee vetoed changes to state growth management rules that would have relaxed restrictions on development in rural Washington. A long-sought rewrite of the state’s business tax system has not materialized. The $8.7 billion tax cut passed in 2013 to appease Boeing is a particular sore spot.

Olympia makes laws tailored to urbanizing communities in Puget Sound, Ferry County leaders argue, not struggling rural communities outside the metropolitan belt.

“Seattle policies do not work here,” said State Rep. Jacquelin Maycumber, R-Republic.

Two of Ferry County’s biggest obstacles to economic development are the poor broadband access and cellphone coverage.

Rep. Richard DeBolt, R-Chehalis, introduced a bill meant to tackle the so-called “last-mile” problem — linking homes, businesses and schools to telecommunications infrastructure. DeBolt proposed a $300 million fund to upgrade rural broadband services. The bill died after legislators could not agree on where to dig up the money and how to allocate it. Ferry County legislators hope the bill will be revived in 2019.

Ferry County’s legislators also want to change the business and occupation taxes to lighten the tax burden on small rural businesses, which are essentially the only kind that Ferry County can support. For years, Republicans and Democrats have complained the B&O taxes — a tax on a business’ gross receipts — hurt small businesses because gross receipts are much larger than the profits. Small businesses are essentially all Ferry County can support.

But modifying B&O taxes is extremely complicated. Legislators who criticize how B&O taxes are set up also punt on the work to change them.

Finally, Short managed to get a bill through both the Senate and House in the 2018 session that would have loosened up Growth Management Act requirements for Washington’s rural counties, such as Ferry and Okanogan. Short contended the act’s current land use requirements are less relevant to rural counties than their densely populated counterparts. This impedes rural economic development efforts by limiting rural counties’ abilities to attract and approve needed new businesses, she contended.

However, Inslee vetoed most of the bill’s breaks that would have gone to rural counties. “The governor gutted the bill,” Short said.

As Ferry County boosters pin their future on a new mine, work is underway at Buckhorn to deal with that mine’s environmental legacy.

During the mine’s operations, Buckhorn’s owners were repeatedly cited for violating state environmental rules. Regulators worry contaminated water from the mine could carry heavy metals to nearby streams. As recently as August, investigators have found higher-than-allowed levels of pollutants, including arsenic, in monitoring wells near Buckhorn.

“The contamination has been going on since the mine began operating,” said David Kliegman, executive director of the Okanogan Highland Alliance, a local mining watchdog organization.

State environmental regulators have $34.9 million provided by the mine owner to fund restoration at the site. Planned improvements include a new system to treat contaminated water from the mine.

Kliegman criticized the state for not pushing Kinross enough, especially on identifying the path contaminants take off the site.

“The company is doing a good job of reclaiming the surface of the mine,” Kliegman said. “But the contaminants in the ground water, that’s the problem.”

Ferry County’s best hope for renewal lies with Adamera.

Adamera, which employs 10 to 20 people in the area, bought mineral rights to potentially lucrative land in Ferry County. The company doesn’t actually do the mining. Instead, it hunts for gold strikes large enough to make mining profitable and, if any are found, sells its mineral rights to a mine operator.

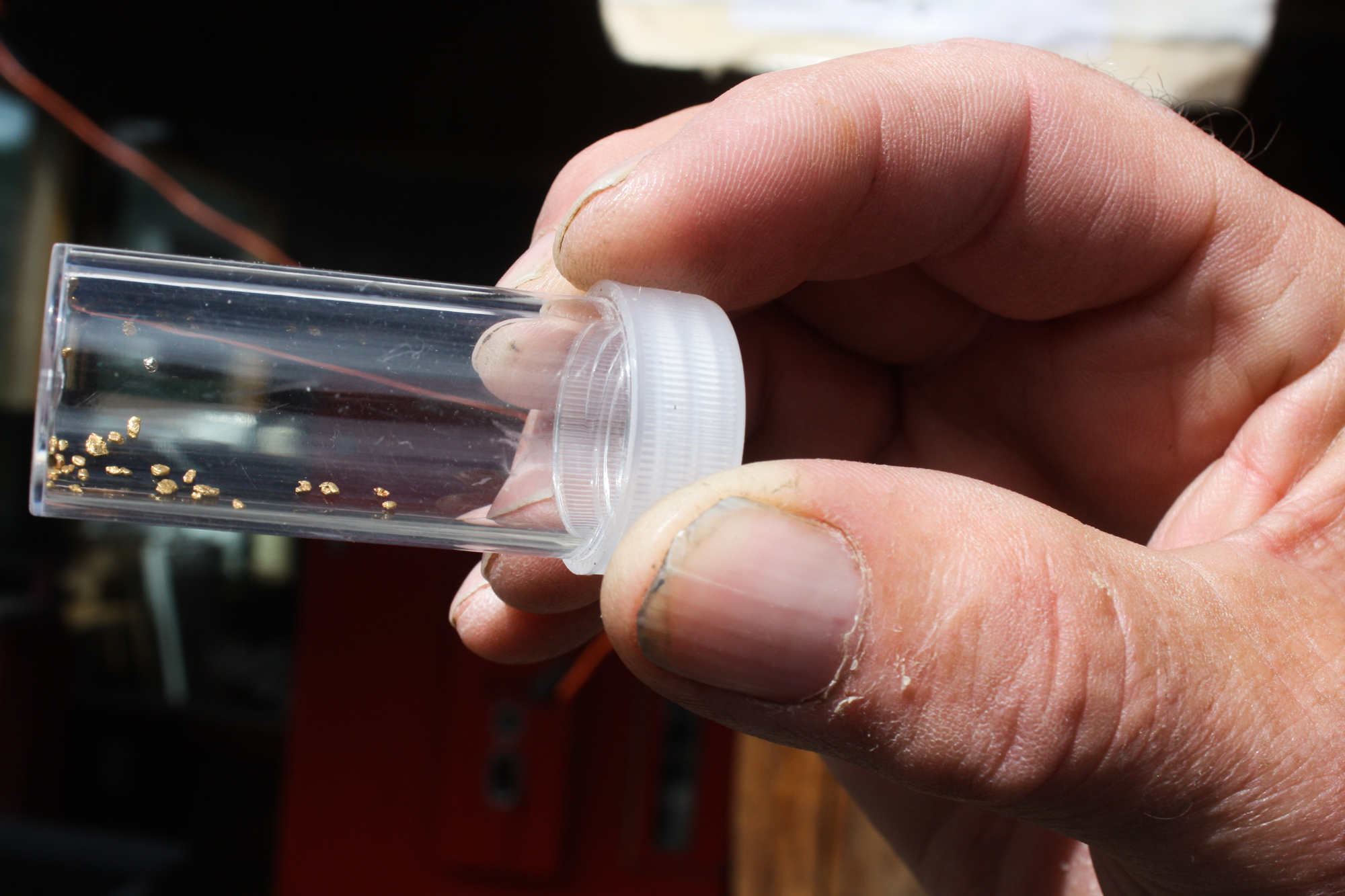

Adamera prospectors have found gold concentrations that are mineable, at least in theory.

Mining companies want a few grams of gold in each ton of ore that is mined. At least 3 grams of gold per metric ton of ore are the minimum needed to making gold mining profitable. So far, Adamera has found gold concentrations as high as 19.4 grams of gold per metric ton of ore, though the size of the deposit remains unknown.

The modern-day prospectors study old maps and the rocks on the surface. They use a low-flying helicopter with a magnetometer hanging beneath it to hunt for metals. Drills collect ore samples from deep beneath the ground to be analyzed in labs. And they shock the earth.

One of Eich’s job is to send electrical currents through the earth to poles pounded into the ground 25 meters and 50 meters apart. A charge zaps into the ground to build up like in a capacitor; Adamera workers measure how long the charge holds to create a better picture of what is beneath the surface.

“It’s the ultimate detective work to see what is happening here. It’s really complicated,” company owner Kolebaba said.

“It’s high-risk, high-reward,” Eich said, "and the reward is huge.”