“To let fires burn in July and August is ridiculous.” — Idaho Gov. Cecil Andrus in the New York Times, Sept. 22, 1988

Rich Fairbanks walks a forest trail through a stretch where two wildfires have burned in the last six years.

The ground is mostly bare, and the tree trunks are striped with black, scorched bark.

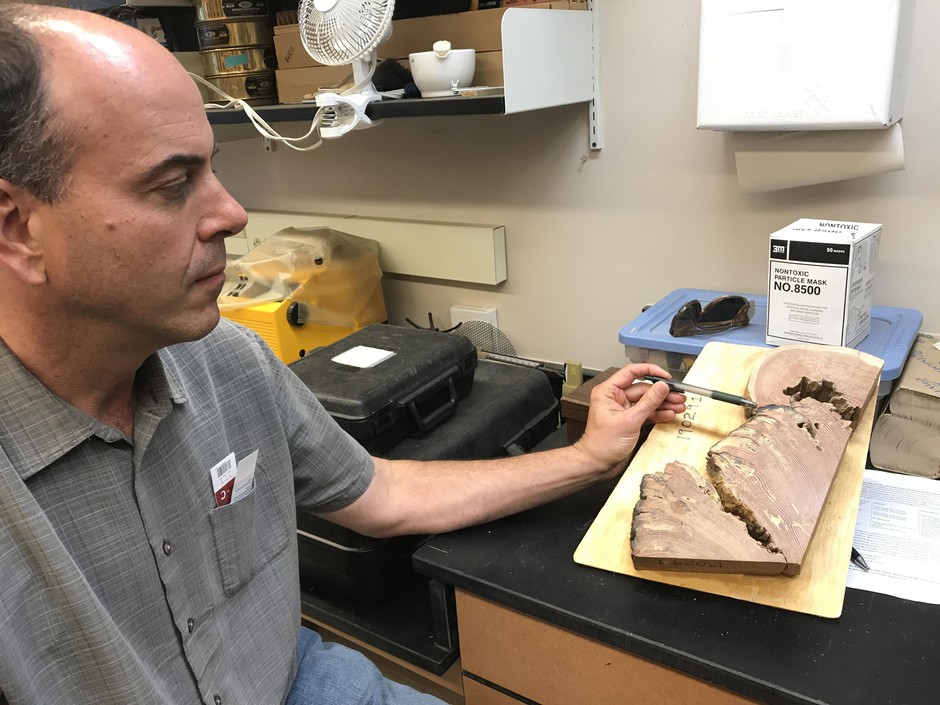

Fairbanks has worked for the U.S. Forest Service as a wildland firefighter and as a wilderness advocate. He is thrilled by all this. He points up at the green crowns of the trees with delight.

“Some beautiful hardwoods in here!” He exclaims. “Look at those canyon live oaks – really nice! They all made it.”

Last summer, the woods were on fire to the right of this trail in the Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest, which straddles southwestern Oregon and northern California. But the flames died out soon after crossing the path — when they reached a part of the forest that had already burned in 2012. The old fire had taken out all the plants and brush that would have served as fuel.

“What they had was a very gentle kind of fire,” Fairbanks said. “It just all around was a good fire in many ways.”

This may sound like an odd way to talk at a time when catastrophic wildfires are burning throughout the arid West, literally causing death, widespread destruction and choking smoke that hangs like a funeral shroud over many communities.

But a variety of forest experts say that one of the best ways to reduce the threat of these mega-blazes is to use fire itself. They say we need to increase the pace of prescribed fire and let some wildfires continue to burn when it’s safe to do so.

Of course, there’s not nearly as much political support for letting fires burn as there is for putting fires out.

“Our knowledge of fire proceeds forward, and there’s always a lag between what we know and what the general public understands,” Fairbanks said. “And even lagging behind that is what the politicians are willing to act on.”

The politics of a smoky future

John Bailey, a forestry professor and fire expert at Oregon State University, said contrary to what Smokey Bear and the U.S. Forest Service once told us, “there is no smoke-free future” in western U.S. forests. We either use fire as a tool to help clear out the dense undergrowth, he said, or we wait for it to be done by explosive wildfires driven by the worst weather conditions.

“If you make me king and I’m able to control the future,” Bailey said, “I’ll burn thousands of acres at a time. Just burning hundreds of acres isn’t going to get us ahead of this program. It’s still going to leave wildfire doing most of the work.”

In practice, that’s harder to carry out, in part because politicians who represent fire-prone regions are reluctant to tell their smoke-weary constituents that there sometimes needs to be more fire in the forest.“Our members of Congress know that overall the public doesn’t like to breathe smoke,” said Andy Stahl, who heads Eugene-based Forest Service Employees for Environmental Responsibility. “The public doesn’t like to feel threatened. The public thinks firefighters are heroes, and they want the fires put out.”

Oregon Rep. Greg Walden, R-Hood River, represents eastern and southern Oregon. He is well-versed on wildfire issues.

He said fire can indeed be “a management tool when appropriately applied.” But in an interview with OPB, the Republican lawmaker was quick to raise several caution flags.

“We’re a long way from being ready to just say, ‘Oh, we can do prescribed burns throughout the forest. Let ‘er burn,’” Walden said. “I don’t think that makes a lot of sense.”

U.S. Sen. Maria Cantwell of Washington is the top Democrat on the Senate Natural Resources Committee, and she’s introduced legislation that includes a bigger role for prescribed fire. However, she was quick to raise concerns about the practice as well.

“To me, one of the key issues in thinking about prescribed burn is that in hotter, drier conditions you have to be very careful,” Cantwell said. “There probably are some examples where people thought they could do prescribed burn … and what they found is it got out of hand really quickly because of those weather conditions.”

Some key members of Congress would simply like to avoid the subject. U.S. Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., has been one of the most visible legislators on wildfire issues. He’s urged the Forest Service to beef up its fleet of aerial tankers, and he worked hard to revamp the agency’s budget to provide more money for fire prevention.

But the normally loquacious senator turned down a request for an interview on the subject of using fire as a management tool.

Contrary to Northwest politicians’ concerns about controlled burns, they are typically set during spring and fall, when conditions are less hazardous.

More support for thinning than burning

Bailey, the OSU professor, said thinning the forest first and applying controlled burns afterward can reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfire in forests that are overstocked with trees from a century of wildfire suppression. Northwest politicians are eager to support the thinning part of that equation, but they’re less enthusiastic about the burning.

Several legislators said that fire is hard to use as a tool when the forests are so much more densely stocked than they were 100 years ago.

“We’ve got to manage back to a point where you can regularly allow fire,” said Democratic Rep. Peter DeFazio, whose southwestern Oregon district regularly grapples with wildfire. “I mean, a lot of these forests are in a condition where you can’t go in with fire because it’s just way too dense.”

Political barriers might explain why some forest restoration projects complete the thinning but not the burning part of the plan.

Bailey said the effectiveness of the dual treatment regime of thinning and burning was demonstrated during the 2017 Milli Fire that threatened the town of Sisters in the Deschutes National Forest. The fire roared through an area that had been thinned and burned by prescribed fire just a few years ago — and Bailey said that the treated area helped knock the Milli Fire down. Without that, he said, Sisters “would have been at the mercy of what the weather was doing.”

That experience has helped change local attitudes. Sisters Mayor Chuck Ryan wrote a letter to the state supporting the greater use of prescribed burns.

“While we may be reducing near-term exposure to smoke by limiting prescribed fire now,” he wrote, “it comes at the expense of future Oregonians who will face increasingly severe wildfires and wildfire smoke.”

Prescribed burning is only part of the equation. Bailey and other experts say the Forest Service should be more determined to let some fires burn. It’s the only way, they say, to make big reductions in that catastrophic fuel buildup.

“Most ignitions happen during much more modest fire weather conditions,” said Bailey, when it’s cooler, wetter and safer to let the fire do some of the work of reducing fuel loads.

Ironically, he said, those are the easiest fires to extinguish, but putting those fires out “just kicks the can down the road to when the wildfires only happen under the worst conditions.”

The notion of letting some fires burn is something not too many lawmakers want to endorse.

“Maybe if you’re in the middle of a wilderness area that has no abutting private property, that’s just fine,” said Rep. Kurt Schrader, D-Ore. “But the real world is, in most cases, there are businesses and homes in some proximity.”

New rules would allow more fire in the future

Even if legislators are hesitant to push forward on using fire as a tool, there are signs of change.

This year’s congressional budget deal included provisions aimed at allowing the Forest Service to keep its budget from being cannibalized by rapidly rising fire-fighting costs. As a result, there’s broad hope the agency can start working its way through a huge backlog of forest restoration projects.

In Oregon alone, there is planned work on about 1.6 million acres that has passed environmental reviews but has gone unfunded. Prescribed fire has been recommended for about half of that acreage.

Vicki Christiansen, interim Forest Service chief, told Congress that “we have to use every tool in the toolbox for treating those hazardous fuels … That is also using fire when we are in control of fire because fire will reduce fuel loads in many of these ecosystems.”

Back in Oregon, the state departments of Forestry and Environmental Quality are working to ease the state’s stringent smoke management rules, making it easier to issue the permits needed to conduct controlled burns.

State Forester Peter Daugherty said current rules prohibit any visible smoke in communities. The revamped rules, which are still under study, would allow some exceptions for a short duration if there are measures in place to protect people particularly vulnerable to smoke.

“There could be a significant increase in the use of fire if we had the resources and can effectively protect populations,” said Daugherty, adding that it “would help protect [us] from fire as well as from wildfire smoke in the long run.”

Richard Whitman, DEQ’s executive director, said climate-change projections show the coast range becoming more susceptible to wildfire. And thanks to winds blowing eastward across those mountains and into the Willamette Valley, that’s something that could threaten air quality in the state’s major population centers if more isn’t done to reduce fuel loads.

“The frequency and scale of wildfire on the West is going up,” Whitman said. “So this is an issue whether we like it or not … we’re going to have to deal this one way or another.”

Oregonians will have their own chance to weigh in on whether to open the door to more prescribed fire. The agencies will hold public hearings this month in LaGrande, Bend, Klamath Falls, Eugene and Medford. If history is any guide, several of these cities could be under a smoky haze at the time.