The media script then was virtually identical to the current one, judging from news clippings from the time.

On Dec. 17 of ’24, a 13-year-old school boy named Jimmy Fehlhaber was walking through a snowy canyon in the woods, reportedly looking for lost mules near his foster father’s ranch outside the community of Olema in Okanogan County. He never returned home. A neighbor went to look for him and found signs of an attack in the snow. A cougar had apparently jumped Jimmy from the rocks above the canyon, a struggle ensued. Jimmy had tried to run but the animal chased, dragged him down and finished him off with a bite to the neck. It took people a while to find the body, which the cougar had dragged back to the base of a cliff and partially devoured.

The horror of the attack sent chills through people who lived in cougar country. Jimmy’s death made news from the Northwest to the Midwest, places where cougars were still a factor or at least a recent memory in rural life. “Cougar Devours Schoolboy,” read one headline. “Child’s Death Brings Mountain Lion War,” declared another. People who lived in cougar country had generally regarded cougars as deadly nuisances to livestock but assured themselves that the animals are afraid of people and afraid of human scent. One newspaper speculated, “Folks in the neighborhood [of the killing] regarded the beast as a sneaking coward when faced by human beings, but now their ideas are changed.” Living with man-eaters was something else.

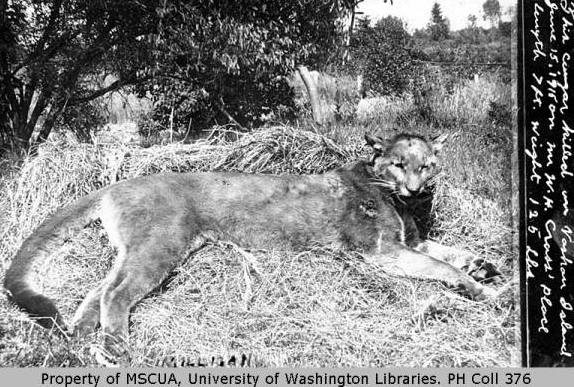

A group of hunters was assembled, including a government hunter with a pack of bear-hunting dogs. They proceeded to track the cougar, distinctive, one account reported, due to a missing claw on one paw. The animal wasn’t starving because he had attacked other livestock in the area. But it was no easy kill. In fact, it took some weeks and a couple of dead cougars — including an innocent, emaciated female — before the hunters got what they believed was the right animal. The cat’s stomach contents were checked and samples sent to experts in Berkeley, California, where it was determined that blonde hair found in the stomach was human hair from a young boy, possibly German or Scandinavian. It matched Jimmy’s. Some small bones found in the cat’s gut were believed to have come from the boy’s gnawed forearms.

Folks were jittery, especially in areas near the attack. A story datelined Wenatchee at the end of January 1925 indicated that animal attacks were on the rise. A 13-year-old boy named Verne Smith was said to have been attacked by a lynx while walking home from school. He shot and wounded it and was able to escape with the help of his dog. A farmer finished the lynx off with a shotgun. Another boy, 16-year-old Arthur Parsib, was attacked by a rabid coyote and killed it. The short item mentioned that these two attacks on students in “mountain country” had caused “many pupils, even the younger children, to carry rifles” between school and home. Suddenly, guns in schools didn’t seem so crazy in wild country.

An Iowa newspaper tried to find humor in the animal attacks saying that “Eat Wenatchee Apples” was a nationally known slogan, “but wild beasts around Wenatchee insist on meat.” “If an apple a day would keep the cougars away, Wenatchee would be well fixed. But wild cats can’t live on fruit.”

Alarms were also raised about the threat posed by the big cats in the region. A Montana newspaper warned that “a scourge of cougars, the big cats of the Northwest forests, imperils livestock of isolated settlers, deer, elk, and game birds.” The article listed a litany of cougar threats for Hood River, Yelm, Sequim, Queets, Concrete, Rockport, Wallula and other communities. “The cougar is the most elusive, sneaking, adroit hider and shyest creature in the woods. Settlers living for 20 years on the edge of the forest have heard its yowling and seen its tracks, but not a hair of a cougar.”

Still, there’s nothing like an attack by a cougar on humans to bring renewed scrutiny and a reflections on the meaning or cause of an attack or, more broadly, what it means to be in wild country.

In the case of Jimmy Fehlhaber, it wasn’t madness or starvation that drove his predator. Being in the wrong place at the wrong time with the wrong cat is probably the best explanation we have.

Thanks goodness it happens so rarely.