“There were people who believed an airplane that big couldn’t fly, just physically,” Lombardi said. “The wife of Joe Sutter, father of the 747, was in the grocery store and someone told her, ‘your husband is working on a plane that won’t fly.’”

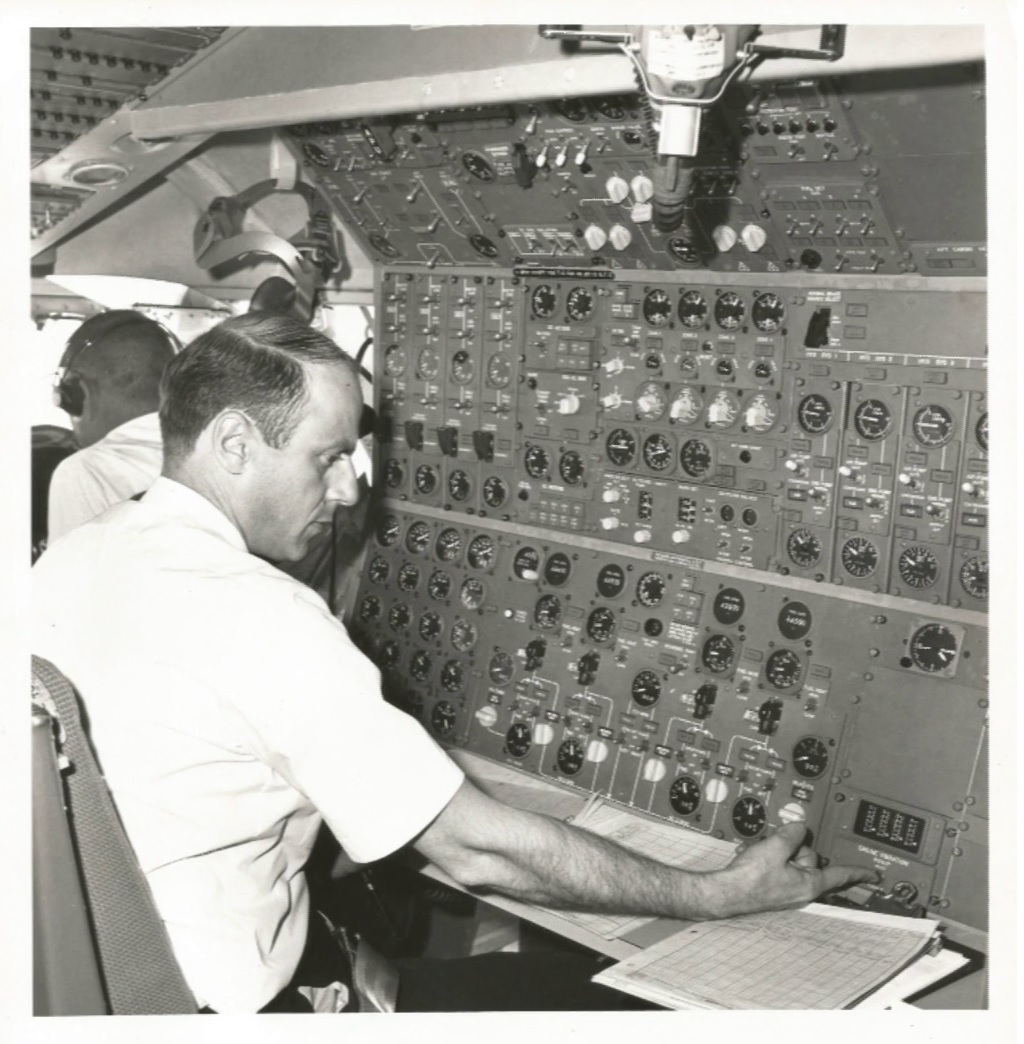

Brien Wygle always believed the jumbo jet could fly. And on February 9, 1969, he was one of two test pilots at the controls who proved it. On that flight, the plane handled well and the Incredibles cheered and shed a few tears as the pilots got out of the cockpit and headed down the stairs.

“I think it was a huge relief to everybody, including our CEO and the executive, that we had accomplished our first flight with no major difficulties,” Wygle said.

A bumpy start

Those difficulties came soon enough. The biggest problem was that the engines sometimes surged. “The temperatures would rise — dangerously so,” Wygle said. “You had to shut the engine down.”

“I can remember one of the vice presidents screaming ‘Do something! Redesign these engines!” said Pat DeRoberts, a flight engineer who helped design part of the cockpit. He was a member of the three-man crew that was ordered to fly the second prototype 747 across an ocean for the first time, to the Paris Air Show. The plane had only 10 flight hours on it. The range of the 747 was untested. Most worrisome: the engine defect hadn’t yet been solved. But Boeing was so overextended financially it needed to sell some planes fast.

“As soon as we took off for Paris, all four engines went into overheat,” said DeRoberts. Rather than turning back, the crew decided they would get some speed going and hopefully that would cool the engines down.

“One by one the overheat lights went out,” DeRoberts said with a big smile. “And phew! We are on our way!”

The gargantuan plane was a hit at the Paris Air Show and orders followed. Then engineers worked frantically to get to the bottom of the surge problem.

“During the flight test program...we had 55 engine changes,” says DeRoberts. “I’m talking about engine failures. Remove and replace.”

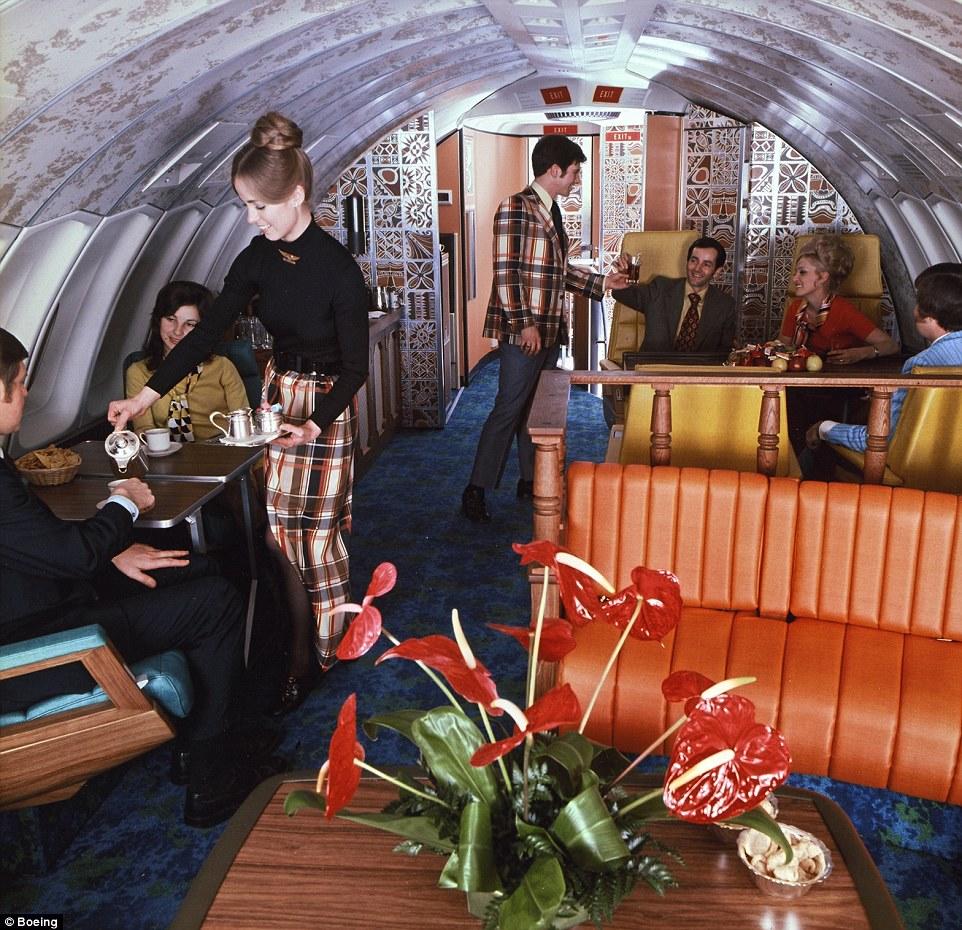

Long story short, Boeing solved the engine surge defect in time for Pan Am’s first scheduled flight of the plane with paying passengers in January 1970. The plane was an instant sensation, in part because of its distinctive hump and the spiral staircase that led to the bar that Pan Am put inside that hump. Before long, lots of airlines had to have their own 747s with that bar behind the cockpit, kicking off the glory days of drinking at 30,000 feet.

“Actually there were three lounges on the airplane,” Cheryl Grimm said, looking around the mod “Mad Men” bar inside the hump of the prototype 747 at Seattle’s Museum of Flight. “There was this one, which was for first class, and there were two in coach: one at the front of coach and one at the back of coach.”

Grimm was a stewardess — yes, that’s what they were called — flying to Hawaii on the first 747s purchased by United Airlines. She describes a scene unrecognizable in these days of no food, no bar, no free luggage, no free drinks, and no leg room: In the early 1970s, free-range passengers roamed to the various lounges drinking tropical cocktails while live ukulele players in native dress serenaded them.

“It was a huge, new airplane and everybody was excited to be either a passenger or a crew member,” she said, adding that it wasn’t a free-for-all. “It was the era of wearing hats and gloves, so people acted that way.”

A new lease on life

Those days are over. But there’s no need to bring out the hankies just yet. The endangered jumbo just got an unexpected second lease on life.

In February, United Parcel Service ordered 14 freighter iterations of the plane. That will keep Boeing’s 747 line humming along awhile. And there is a glimmer of hope from President Trump that, despite his earlier complaints that Air Force One is too expensive, the federal government will most likely green-light the conversion of two existing 747s into the next generation of Air Force One.

A few overseas airlines like British Airways are still flying passenger routes with this venerable plane, too, but those days are numbered. With each passing month, more passenger 747s, including the Delta plane we began this story with, are rusting away in airplane graveyards in the desert.

“All things fall into obsolescence,” test pilot Wygle said without obvious emotion.

Grimm had a harder time hiding her feelings as she walks around the bar of the first 747. “It’s like saying goodbye to a good friend,” she said, lightly touching the surface of the tables and skirting past the groovy sofas. “Good old days,” she murmured, before descending the spiral staircase.

For people came of age along with this plane, the 747 will never be a white elephant. They prefer to remember the days when the jumbo jet stopped traffic — a time when we were ferried around the world like royalty-on board the Queen of the Skies.