Young Jean Soliz didn’t notice the dead man crumpled in the doorway of his Richmond Highlands home that snowy night in 1969. She and her mother were hurriedly responding to a call they’d just received from the man’s frantic wife.

“Ed’s been shot!” neighbor Bettye Pratt said in the call, which she made after phoning the sheriff for help. When they arrived, a deputy was already standing guard under the carport of the modest Shoreline neighborhood home. He told them to go around to another door, where a distraught Bettye gave them the bad news.

Her 38-year-old husband, Edwin Pratt, a black-community leader and director of the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle, was dead, ambushed in his driveway by two assassins who disappeared into the darkness.

“I didn’t see his body out there so we were shocked,” Soliz recalled recently between sips of coffee at a Tacoma Starbucks. Once the Pratts’ neighbor, babysitter and a member of a group that helped the Pratts start an interracial church in north Seattle, Soliz, who is white, is finishing up a book on the murder — the Northwest’s major unsolved civil rights assassination.

Officially unsolved, that is. The murder case is almost a half-century old — the 49th anniversary is approaching this month — and investigators have determined who did it and why. As I learned while reporting on the case for a 2011 Seattle Weekly article, three white men carried out a racially motivated hit on a black civic leader. (Some of the details in this story came from records and other sources I interviewed then and appeared in the Weekly story.)

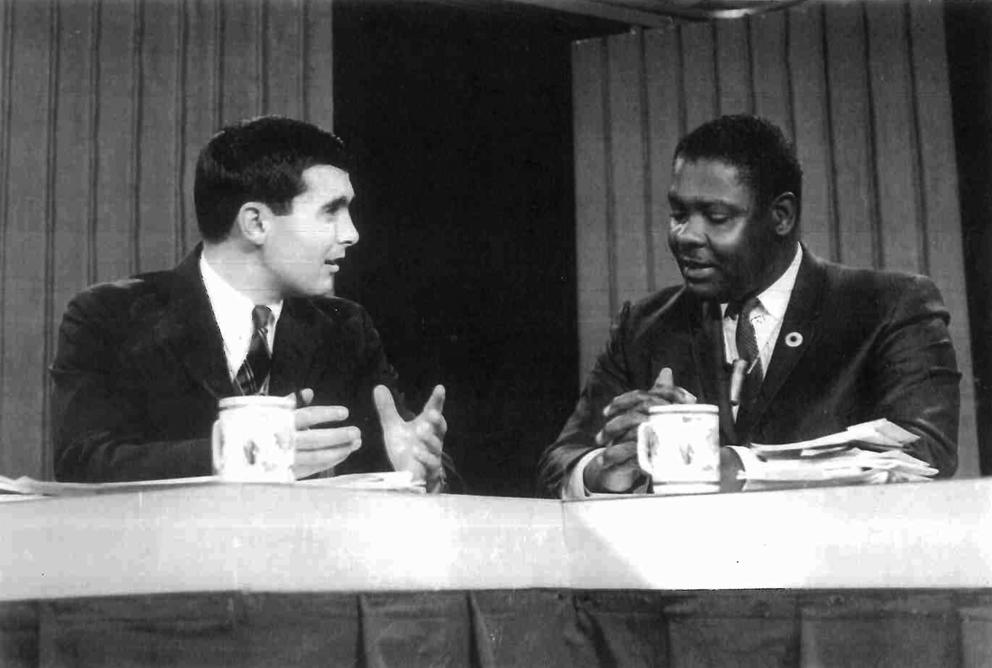

Pratt urged Seattle’s people of color to rail against inequities in hiring, education and housing, including redlining, a banking practice that constricted approval of new home mortgages in ethnic neighborhoods.

To some, the civil rights leader was a troublemaker. But who wanted him dead, and was willing to pay for the favor? All these years and thousands of hours of investigations later, cold-case probers are still seeking the final puzzle piece.

Soliz, however, thinks she’s close to an answer. If she’d known then at age 22 what she knows now as a 70-year-old Olympia writer, researcher and former state official — once heading up the huge state Department of Social and Health Services — Soliz says, “I probably wouldn’t have been so stunned” that deadly night.

Pratt’s murder came at the end of a decade of deadly violence against community and national leaders — most notably, the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy and the 1968 shootings of presidential candidate Bobby Kennedy and Nobel Peace Prize winner Martin Luther King Jr. Like them, but on a regional stage, Pratt became a marked man for challenging racial and political norms.

Recalling another assassination, the 1963 shooting of Mississippi civil rights leader Medgar Evers by a member of the Klu Klux Klan, Bettye would later tell investigators that an anonymous caller warned her in 1964, “If Ed doesn't shut up, he'll end up like Medgar.” He did. Both black leaders were murdered by white racists armed with rifles, waiting for them in their driveways — in Seattle and Jackson, Miss., 2,500 miles and six years apart.

Like Evers’ death — which President Trump recently brought up during an awkward speech at the new Civil Rights Museum in Jackson, calling the work by Evers and other rights crusaders “big stuff…very big stuff” — Pratt’s murder reverberated across the U.S., and drew a crowd to his funeral at St. Mark's Cathedral on Capitol Hill. Whitney Young, national Urban League director, told attendees, “I sense some shame that this could happen here,” a racial murder in a mostly white but reputedly tolerant northern city.

An arts center and a park in Seattle were named for Pratt. Shoreline, which did not incorporate until 1995, moved on. But, through an online petition drive started by a Shoreline third grader, about 1,900 signatories are today urging the school district to name one of its buildings after Pratt. The student, who gives her name as just Sarah, said she only recently heard about Pratt and hopes to honor him because “he was an important person and he had a huge impact on others.”

Pratt was aware that his trailblazing agenda — including a hard push for integrating neighborhoods and an end to police harassment — was creating enemies. Mustachioed, well-built, with a friendly demeanor, he attracted wide, biracial support among moderates. But his rhetoric also united others, black and white, in opposition.

Pratt's white secretary told police many of his detractors were African-Americans and the more militant ones vowed to “eliminate” him. “Uncle Tom” was one of the milder phrases Pratt was accustomed to hearing.

He refused to react to the danger, and investigators had to ask whether he had added to it: Pratt was having a secret affair with the secretary, investigators learned, and had recently asked Bettye, his wife of 13 years, for a divorce. Her response? She threatened to kill Ed if he left her.

“I was babysitting for Bettye the night she found them together,” says Soliz, who is devoting most her time now to probing the murder. “Bettye went looking for Ed and found him with his girlfriend at the movies. She came home in tears, and was a wreck.”

Ed Pratt persisted nonetheless, and planned to meet the secretary for dinner at her apartment on the night of Jan. 26, 1969. But due to an unusual heavy Seattle snowfall that Sunday, he canceled.

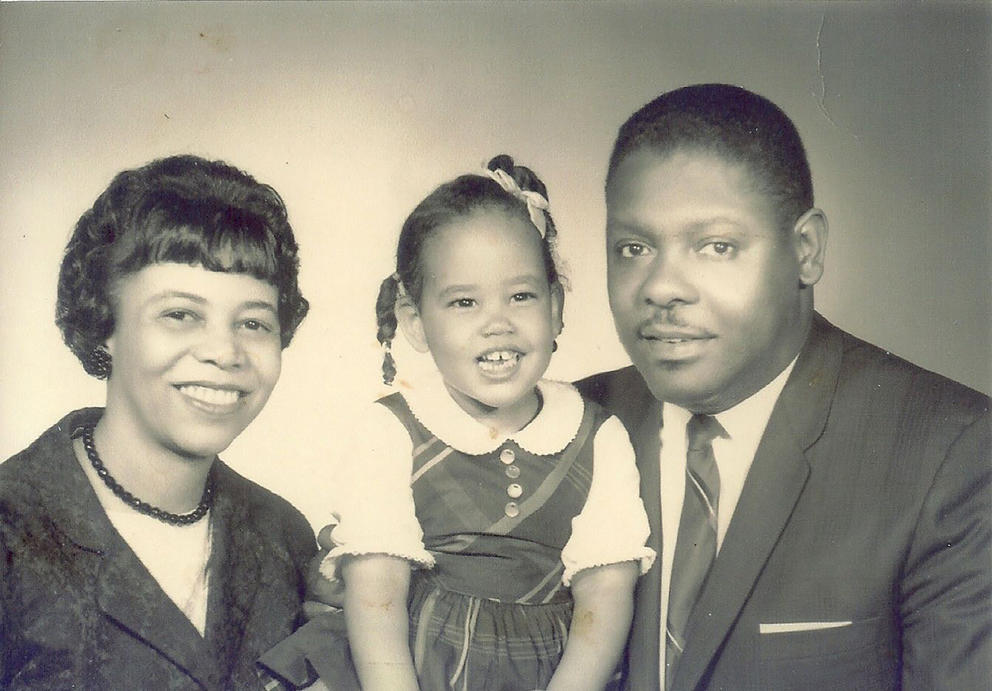

Pratt relaxed in his living room chair at their home in the 17900 block of First Avenue NE. He watched TV while Bettye put their 5-year-old daughter Miriam to bed. They were Southerners who'd grown up poor in the 1930s and met in the 1950s while attending Atlanta University, where he received a masters degree. They moved to Seattle after their marriage when he became the Seattle Urban League's community-relations director, moving up to executive director in 1961. He liked the work, disturbing the dust of racial contentment.

Startled by the sound of snowballs suddenly hitting the side wall of their rambler, Ed Pratt went to the door, opened it warily and asked, “Who's there?”

A shotgun blast ignited the scene and sent a slug tearing into Pratt's mouth, glancing off bone and severing his spine before lodging in his neck. He collapsed in the doorway as Bettye, who'd been watching from a bedroom window, saw the muzzle flash and shouted, “They've got a rifle!” Most likely, an autopsy later indicated, her husband was already dead.

Neighbors told police they spotted two young men hop into what some guessed was a 1968 Buick Skylark, driven by a third man. “They looked like kids,” said a witness. “It was the way they ran — their gait.” And their race? Some insisted they were white, others though they were black.

Seattle, which considered itself a melting pot of progress and civility, was witnessing what it might be like to deal with a Southern-style racial assassination. National leaders sent condolences. President Richard Nixon dubbed Pratt the Martin Luther King Jr. of the North.

Investigators had little to go on, however. The scant evidence included a 12-gauge slug taken from Pratt's body, tire tracks and footprints in the snow. “The snow was frozen but scuffed up and broken” from all the foot traffic, Jean Soliz remembers. She can’t imagine how investigators obtained any usable or untainted evidence from the trampled crime scene.

Despite Nixon’s comment comparing Pratt to King, my research for the Weekly showed that his administration may have preferred not to have the killing blamed on whites. U.S. Attorney General John Mitchell said in a teletype message to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover: “It has come to my attention that certain black groups are circulating a story to the effect that the death of Pratt was caused by White racists. Does your bureau have any information to the contrary, and, if so, is there any way it might be publicized through local police or otherwise?”

Despite a $10,000 reward (about $70,000 in today’s dollars), no one was ever arrested or charged with the crime. But after the case went cold for 25 years, it warmed up in 1995 when the Seattle Post-Intelligencer broke new ground, citing witnesses who said two white men had committed the crime and had been overheard bragging about it.

The two were Tommy Kirk, 21, a violent street thug, and his accomplice, Texas Barton Gray, 49, an armed drug dealer. A third person, unidentified, drove the getaway car, the P-I reported.

Investigators told me they believed the information to be accurate. But Kirk and Gray were the messengers. Who, detectives still wondered, ordered the delivery, and how much did it cost? In 2011, after obtaining the Mitchell-Hoover papers and then plowing through stacks of the county’s cold case files, I came up with some additional answers.

Based on documents and interviews with detectives and two witnesses who were with the three-man hit team after the murder, I was able to confirm that Kirk, described as a psychopathic, trigger-happy drug dealer, fired the shot that killed Pratt, while Gray, a longtime drug dealer and gun peddler, was his lookout.

Detectives and the witnesses had now identified the third man as Michael Lee Jordan, then 22, a small-time criminal who drove the getaway car. As I wrote then, all were white, all were dead, and all may have shared as much as $25,000 to kill Pratt, investigators indicated.

Cold-case detectives suspected a black contractor named Henry Roney was most likely the man who paid for the shooting. Known for his dislike of Pratt and their ongoing spat over how to reform construction hiring practices, Roney was questioned only days after Pratt's death. He was considered a leading suspect because “No one had a greater motive,” a detective told me. “When you look at the evidence, it's very compelling.”

But Roney, who died two decades back, had denied any role in the shooting, and his ex-attorney told me Roney was wrongly accused. Author Soliz says she doesn’t believe Roney was the money man either.

Her research points to a “group” of sponsors willing to pay for the hit. “I can’t tell you yet all I’ve learned,” she said, “but it will be in the book.”

There’s also the possibility Pratt was killed by someone who was simply a racist and would gladly do it for free — someone like Kirk. Danella Jordan, the widow of getaway driver Michael Jordan, told me she was with her husband, Kirk, and Gray just hours after the Pratt shooting, and there had been no talk of a behind-the-scenes sponsor.

Jordan instead fingered Kirk as the idea man. He was a loose cannon and racist, she said, and the shooting was a “monumental hate crime” committed essentially by one man. Kirk never mentioned the name Roney, she recalls, but he did mention Ed Pratt.

“Tommy had heard about Pratt,” said Jordan, who now lives in another state. Pratt “was all over the news, and [Tommy] stated he was going to shoot 'that rich n---,' or words to that effect. I honestly don't recall money being the motivation.”

Her husband apparently bought that theory too, based on a statement he gave the FBI in 1995, when the agency briefly reopened its probe following the P-I story. Interviewed in his Walla Walla prison cell where he was doing time for robbery, Jordan said Kirk killed Pratt for “being a black dude in a white neighborhood.”

Jordan never flashed any extra cash during that period, said his widow — they lived off drug sales money at the time. But then, he “was wildly in love with a Texas whore, running from the Texas Rangers,” the widow said. “If he had big bucks, perhaps it was her he spent it on.”

A witness at the Jordan home following that night’s shooting recalled seeing the three suspects enter carrying a shotgun. “Tommy Kirk kind of ah, scared my ass, you know,” the witness told a detective in an interview. “I had enough sense to know that if you screwed with Kirk, he was a psychopath, man.” He proved it that night, the witness said. “God, I have never seen anybody do this in my life, but Tommy Kirk started shooting dope, and it was like, it was, believe me, it was, I, I have never got this, 'cause he had, he had like a jug of this [drug], and…he'd just ‘Bam!’ till it was gone. I mean, he did enough dope that would of killed like all three of us, you know?”

Four months later, Kirk was murdered on Capitol Hill by co-conspirator Gray, sometimes his rival in drug dealing, over money and a woman. Gray died in 1991 of a heart attack following his conviction for manslaughter. Mike Jordan died in 2006 at age 58.

“I went to grade school with Tommy Kirk in Mountlake Terrace,” author Soliz tells me, finishing her coffee, “then grew up as a neighbor of the Pratts.” Years later, she arrived at the Pratt crime scene shortly after Tommy Kirk left it. Weird coincidences, she said, packing up her writer’s notes.

But perhaps she will come up with the defining answers. Or maybe the county will rededicate its efforts, name names and close the Pratt case. In an era when white nationalism is openly practiced with baseball bats like those Tommy Kirk once carried with him, it can’t happen soon enough.