The long hunt finally paid off on the night of Aug. 6 for two employees of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. They’d spent a combined 85 hours and driven 752 miles in pursuit of the Harl Butte wolf pack in the northeast corner of the state.

They had already come close, spotting wolves twice but never firing a shot.

But finally, on a Saturday evening, they killed a young male. Two days later, an Oregon Fish and Wildlife employee fired a kill shot from a helicopter while patrolling the rolling forests and pastures. This time it was a young female.

The wolf-killing mission was meant to halt a pack that was helping itself to ranchers’ livestock.

It won’t work, thought Todd Nash. He and other local ranchers wanted the whole pack gone.

“If there was a gang in downtown Portland and there was 13 of them and you randomly took two, you didn’t know if they were the ringleaders or what they were … would you expect to have a positive outcome?” Nash said.

It turned out Nash was right; it didn’t work.

Weeks later, some of the Harl Butte pack’s surviving wolves tore into a 450-pound calf. It was found dead in a pasture Nash leases, with bite marks across its legs, flanks and hocks.

So Oregon wildlife officials killed two more wolves. Weeks later, they said the depredations had stopped.

They hadn’t. The Harl Butte pack struck again in late September, killing a 425-pound calf.

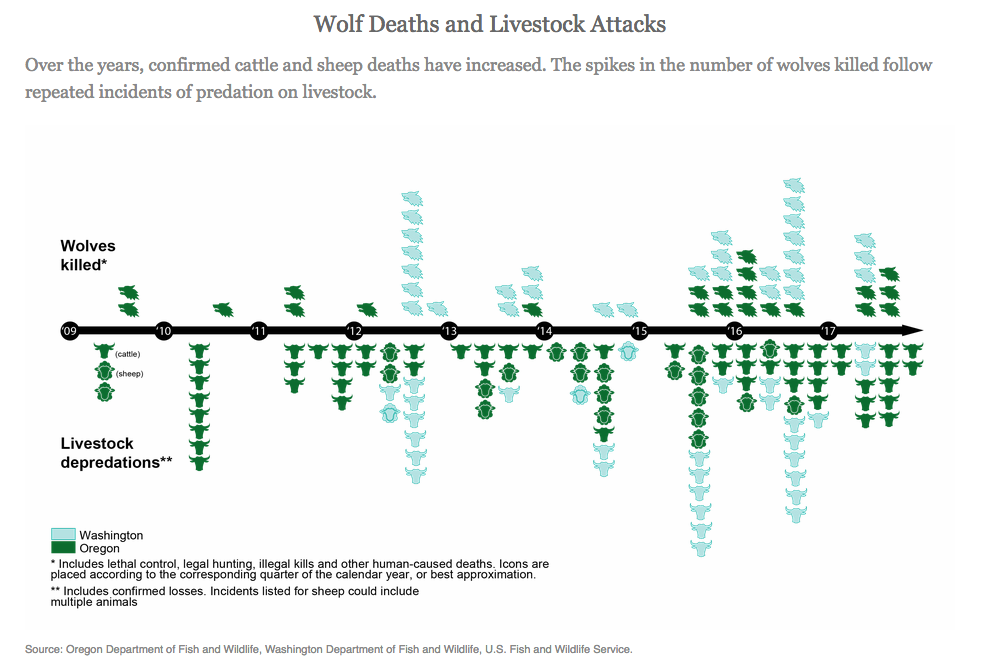

As the number of wolves in Oregon and Washington has grown, wildlife managers are increasingly turning toward lethal tactics to keep them away from ranchers’ livestock. State governments in the Northwest now spend tens of thousands of dollars to kill wolves that prey on cattle and sheep.

State wolf managers are walking a tightrope: growing and sustaining a population of wolves while limiting the loss of livestock for the ranchers who make their living where the predators now roam.

Managing wolves in the West is as much about politics, economics and emotion as it is about science.

“Sometimes you view it as being between a rock and a hard place, or being yelled at from both sides,” said Derek Broman, carnivore and furbearer coordinator for Oregon Fish and Wildlife. “I like to say it’s balance.”

To balance the costs of killing wolves, ecological needs and the concerns of ranchers and wolf advocates, it’s the policy of both Oregon and Washington to kill wolves incrementally — starting with one or two at a time. But in making that compromise between preserving wolves and preventing livestock damage, they’ve taken a course of action that scientific evidence suggests could achieve neither.

Policies and practices in both states go against a growing body of research casting doubt on the overall effectiveness of killing predators.

Neither state follows recent recommendations from top researchers that their efforts to control predators be conducted as well-designed scientific studies. And neither follows the primary recommendation from the research most often used as evidence, which found killing most or all of a pack is the most effective form of “lethal control” to reduce ranchers’ damages.

Instead, some scientists and advocates say, Oregon and Washington are risking harm to the Northwest’s wolf population without ever reducing predation on cattle and sheep.

“Oregon and Washington may be playing with fire in their incremental control approach,” said professor Adrian Treves, who founded the Carnivore Coexistence Lab at the University of Wisconsin. “Not only is there very little evidence for the effectiveness of lethal methods, but there are more studies that find counterproductive effects of lethal control, namely that you get higher livestock losses afterward.”

Northwest wildlife managers say they use lethal control, in part, to increase people’s willingness to tolerate wolves. Treves said there’s little data to support that it’s actually helping shape public opinion to accept wolf reintroduction. In fact, Treves has published research suggesting otherwise: that government-sanctioned killing of wolves may actually embolden individuals to illegally do the same.

Policies under scrutiny

In 2016, Treves was part of a team that published a paper concluding common methods of both lethal and non-lethal predator control were sorely lacking the support of gold-standard scientific evidence. Since 2016, three other papers — independent of each other — found strikingly similar results.

He and others have called on governments to re-evaluate their predator control policies. Treves was also one of multiple scientists who filed comments with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, saying his research and others’ had been misinterpreted in the state’s revision of its wolf management plan, which Treves and others criticized for being biased in favor of lethal control.

“It’s just like (when) the government is putting a medicine out there; it needs to prove the medicine is effective,” Treves said. “ Because there are costs. And not just financial. Animals are dying.”

Lethal control policies in both Oregon and Washington are getting pushback from wolf advocates.

In Oregon, multiple groups have called on Gov. Kate Brown’s office to intervene. The governor’s office has not publicly responded and did not respond to requests for comment.

In Washington, two environmental groups filed a lawsuit in September claiming the state’s approach to killing wolves is unnecessary and that its protocols do not satisfy Washington’s State Environmental Policy Act.

Donny Martorello, wolf coordinator for Washington Fish and Wildlife, said the state has seen mixed results with lethal control.

“We’ve had situations where we’ve initiated lethal removal and had to stay with it for quite a period of time. Removing more and more wolves because the conflict kept going and going and going,” he said. In other cases, he said, it seemed to reduce the conflict.

Martorello said the decision to kill wolves to is not about decreasing long-term livestock losses. It’s about intervening in an escalating situation, where prevention has failed and a rancher’s cattle or sheep are dying.

“We turn to lethal removal as a last resort,” Martorello said. “When we remove wolves it is trying to change the behavior of wolves in that period of time. We can’t extend that to say that will prevent negative wolf-livestock interactions in the long term. Because it doesn’t.”

In its lethal control protocol, WDFW cites a paper from Michigan saying the “the act of attempting to lethally remove wolves may result in meeting the goal of changing the behavior of the pack.”

However, that study’s authors do not make claims about changing behavior, and attribute any lower recurrence of attacks on livestock to the increase in human activity nearby — not anything specific to lethal control.

That study also found no correlation between killing a high number of wolves and a reduction in livestock depredation the following year.

Instead, it found the opposite: “Our analyses of localized farm clusters showed that as more wolves were killed one year, the depredations increased the following year.”

Ranchers say lethal is needed

In Oregon, after killing four wolves didn’t stop depredations, the state eventually issued Todd Nash his own permit to hunt them where his cattle graze. Nash, the wolf committee chair for the Oregon Cattlemen’s Association, also serves as a Wallowa County commissioner.

In mid-October, Nash was hauling bags of mineral feed to where his cattle graze in the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest. He kept stopping along the snowy road.

“That right there is a wolf track,” he said, hopping out for a closer inspection. He spotted another smaller set next to them. “That looks like a pup.”

They were fresh and led toward cattle.

Nearby, a state biologist and the local range rider were doing the same. From time to time, Nash checked in and shared what he knew.

“There’s tracks going both ways,” he tells them. “These were smokin’ fresh.”

In Oregon, like in Washington, wildlife managers only kill wolves if demonstrated non-lethal efforts to deter wolves have failed. Those preventative measures have been adopted inconsistently, and with mixed reviews. Many say they’ve seen improvements by removing bone piles that attract wolves and by increasing human presence. Here, Nash said he’s had someone in the pasture nearly every day, including his own cowboys, a county range rider and a friend he hired to camp nearby.

Cattle die for many reasons on the open range. Wolves account for only a fraction of ranchers’ losses, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture figures. In the Northwest, documented kills by wolves amount to a few dozen per year in a region with more than two million cattle.

But for an individual producer, wolf damage can be a devastating blow. Especially when it’s on top of added stress and added costs of preventing wolf attacks.

Turning cattle out to roam after a long winter used to be a time to relax and celebrate, Nash said.

“You’d go, ‘oh, this is so nice,’” he said. “And now, that’s been taken away from us. I’m sad about that.”

This past summer’s wolf killings are in the same area where Oregon officials previously killed four members of the Imnaha pack. Nash said killing wolves from the Imnaha pack bought ranchers temporary relief from the predators. But, eventually, a new pack moved in.

After a few hours on snowy roads in the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest, Nash had no wolves in his sights. He decided to head home.

“I’m a little disappointed,” he said, patting a black bolt-action rifle resting beside the driver’s seat of his pickup. “I’m definitely nervous. You see how close they are to the cattle.”

In most Western states where wolves live, ranchers can submit claims for financial compensation for cattle killed by wolves. But Nash said that’s a poor substitute for losing one of the cows or calves he takes pride in and cares for.

“We’ll take the no wolves over compensation any day, given the choice,” Nash said. “It’s not in us to allow our cattle to be killed. It’s an act that’s contrary to everything we do.”

Lethal control has broad support from farmers and ranchers. It’s seen as a crucial tool to protect livestock. Government killing of predators is common worldwide — from wolves, cougars and coyotes in the American West to dingos in the Australian Outback. In the United States, the federal government’s Wildlife Services agency has killed more than two million mammals since 2000.

In the dark on what works

But those who study predator control say ranchers and wildlife managers are operating in the dark, with little data to show what works.

“It’s not fair to our farmers,” said Australia-based scientist Lily Van Eden, who published a paper on the subject in 2017.

Examining past studies of the various techniques used to control predators, Van Eden found wide swings in results. That includes two studies of lethal control and one of guardian dogs that all showed increases in livestock losses.

Van Eden’s paper was one of four published in the past two years examining the current landscape of predator control research.

Each team reached the same conclusion: there is not sufficient evidence to say if and when killing large carnivores, such as wolves, actually achieves the desired result of reducing the loss of cattle or sheep. The same can be said for most non-lethal techniques.

Much of the research into the topic of both lethal and non-lethal predator control is flawed in one way or another. Of the research that does exists, more studies showed lethal control efforts to be ineffective or counterproductive at reducing ranchers’ losses.

Without gold-standard research on the subject, existing data can be used to justify opposing positions.

Take, for instance, a study published in 2014 led by Washington State University professor Robert Wielgus. It used data from the wolf population in Rocky Mountain states. The study showed livestock lost to wolves actually increased after some wolves were killed. It was criticized for not adequately accounting for changes over time. A University of Washington team re-analyzed the data and published essentially the opposite finding, only to be criticized for over-correcting and making their own statistical errors.

Exactly how killing wolves could lead to an increase in depredations is not well understood. But there are several possible factors: Removing a pack could allow new wolves to move in, creating disruptions and unusual foraging techniques. Removing part of the pack could displace the remaining wolves to neighboring farms or pastures, who then prey on livestock. Or the pack could be weakened, limiting its ability to successfully hunt its natural prey of elk and deer.

“The information out there is not conclusive,” said the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife’s Broman. “It’s still kind of an early discipline. We look at what pieces of that information are most applicable here and what could potentially work.”

Avoiding the all-or-nothing approach

In 2015, Liz Bradley of Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks led an analysis that found killing wolves does reduce livestock damage. It’s now widely cited by wildlife managers.

That paper’s findings do not wholly endorse what Oregon and Washington are doing when they kill only one or two wolves at a time.

“There wasn’t very much gained by such a small partial pack removal. You gain about two months,” Bradley said.

The study concluded killing one or two wolves from a pack meant an average of about two months until the next wolf kill. With no action taken, that time between wolf attacks was a little less than a month. That’s a marginal difference compared to eliminating the full wolf pack, which resulted in an average of about two years until the next wolf attack. Ranchers like Todd Nash say this is a good reason to favor full pack removal.

Bradley acknowledged removing a full wolf pack isn’t always an option. But if you’re going to kill only one or two members of the pack, she found, it has to be within a week to be most effective. Bradley said her study wasn’t intended to endorse or condemn killing wolves but rather to offer guidance on how to be most effective.

Exactly why, she doesn’t know. But she suspects it increases the likelihood of shooting the culprit wolf.

Washington officials say they aim to respond within two weeks after a depredation. Oregon’s last two state-sanctioned wolf killings were carried out 10 days and 19 days, respectively, after a depredation.

These wolf attacks on livestock often happen in remote areas and go undiscovered for stretches of time. Responding within a week might not always be an option.

“If you don’t do it within the first week or two weeks, then you probably shouldn’t bother,” Bradley said. “After that, we found there was no difference.”

ODFW’s Broman said Oregon is testing out unproven methods like incremental pack killing because it doesn’t want an all-or-nothing approach.

“We’re seeing if it works. It’s still a test to see what we’re looking for,” Broman said. “If you went exclusively by Bradley, you’d either do nothing or full pack removal. Full pack removal is very difficult.”

The problem with non-lethal, and finding a better way

Wolf advocates have pushed non-lethal alternatives to killing wolves to reduce livestock depredations. They advocate techniques like hazing wolves, fencing off cattle or using guard dogs. But there’s also a lack of evidence on those. And they’re also expensive and time consuming for ranchers.

A recent study done in Idaho by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Defenders of Wildlife yielded promising results for non-lethal techniques. Over seven years, researchers found the rate of sheep losses due to wolves was 3.5 times lower in an area where they used only non-lethal techniques, compared to an area open to lethal control. That was in rugged, remote pastures where non-lethal techniques were used.

That was a designed study with funding from conservation groups, the federal government and private donors. The study included field technicians who could help pen sheep at night and employ other wolf deterrents. The study’s author, Suzanne Stone of Defenders of Wildlife, said those non-lethal methods cost less money than Wildlife Services spent on killing wolves in nearby pastures. And those same methods are being used as part of a non-lethal program covering 10,000 sheep grazing across an area of nearly 1,000 square miles.

Most ranchers don’t have the time or manpower to do what that study did, said Julie Young, a researcher for the government’s Wildlife Services.

Young has been working on how to adapt non-lethal practices for widespread adoption.

“Maybe there’s a happy medium,” she said. “We’re going to do these things, but we actually want to measure it as we’re doing it, so we can know if this program we’re investing time or money or resources in is cost-effective or effective at all.”

She said programs like lethal control and compensation for non-lethal measures, including the ones used in Oregon and Washington, are ripe for study.

“We need better data,” Young said. “Otherwise we’re going to also lose trust, if we just start pushing tools on people and they don’t work.”

This story was originally published on OPB/EarthFix.