In the midst of a national storm driven by a chaotic presidency, declining institutional trust and increasing anxiety in blue America, Seattle’s voters did a funny thing. They stuck with the status quo.

The outcome of last week’s election contrast with Seattle’s growing national reputation: From gay marriage to marijuana, from electing socialist firebrand Kshama Sawant to a first-in-the-nation public campaign-financing plan, Seattleites are seen as more than progressive. We’re viewed as experimental.

We can hotly debate whether Seattle voted for progressive options on Tuesday, but it would be hard to argue Seattle opted for experimental. In the two major city races — for mayor and an open city council position — voters had the option of candidates who lambasted “business as usual” and offered policy proposals that were either left-leaning, left-field or both.

A close look at the results really underlines the Election Night commentary from Knute Berger that the status quo — the establishment — did well. In the mayor’s race, Jenny Durkan, a relative moderate with an attorney’s sense of political caution, handily defeated urban planner Cary Moon, a left-leaning iconoclast and political outsider. Labor leader Teresa Mosqueda, who had a lot of experience working with legislators, defeated former Tenants Union leader Jon Grant in his second run for City Council. Neither contest was close. As of Wednesday this week, Durkan led Moon by just under 13 percentage points, and Mosqueda led Grant by almost 20 points.

In the era of Trump – one characterized by an increasingly liberal and mobilized left – how did left-leaning, populist messages land with such a thud?

Before we start, some caveats. We should always be skeptical of tying together a whole election cycle with one neat narrative thread. Seattle didn’t go from electing Kshama Sawant to re-electing Tim Burgess in two years because Seattle voters veered from socialism to moderate liberalism. The electorate’s preferences are often conflicted and complex. Broad narratives tend to ignore that. By the time your Grand Electoral Theory of Everything can explain incumbency rates for the Vashon Island Fire commissioners, it probably doesn’t really explain anything.

Still, though, we have two small landslides on our hand in divisive, ostensibly competitive races. That merits investigation.

The mayor’s race

After the August primary, I wrote that Jenny Durkan qualified as a frontrunner, but that her primary performance – 28 percent in a field of 21 candidates – indicated that she would “need to expand her base beyond the current centrist core in November.” That she did.

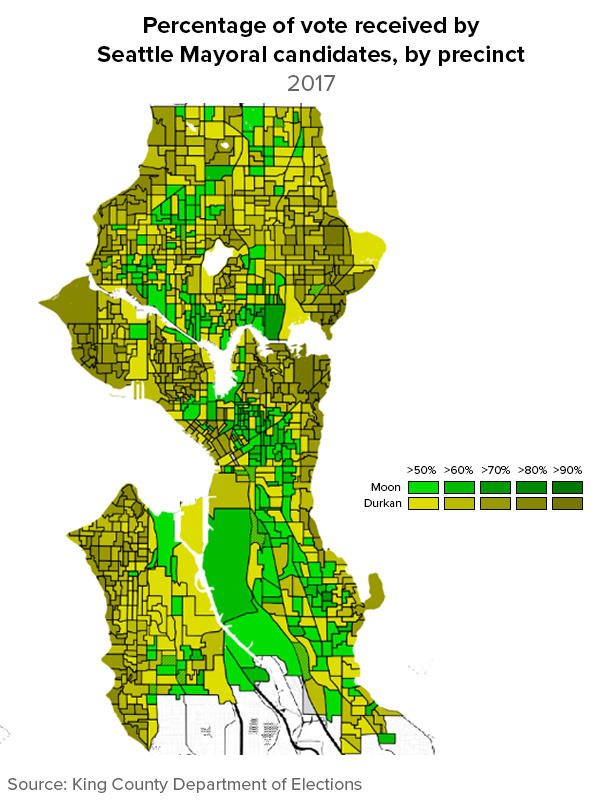

In Election Night results (when Durkan led by 21 points), Moon was performing best in stalwart progressive neighborhoods. Interestingly, and in contrast to her primary matchup with Nikkita Oliver, Moon’s support also appears to have skewed diverse and working-class. Her best neighborhoods were Columbia City (59.4 percent), Georgetown (58.5 percent) and South Park (58.1 percent). Compared to other left-lane candidates, Moon’s performances on Capitol Hill, Fremont and in the post-gentrification Central District were less than electrifying. These underperformances aren’t dissimilar to Mike McGinn’s difficulties in his 2013 mayoral re-election campaign against Ed Murray, whose progressive credentials on LGBT issues allowed him inroads in these same precincts.

Further up the income scale, Moon’s struggles were even greater. At Broadmoor Golf Club, Seattle’s erstwhile Republican enclave, Durkan was above 90 percent in early balloting. She also had massive margins in tony Washington Park (86 percent) and Laurelhurst (85 percent). And many well-to-do areas that are typically battlegrounds in local elections were also solid for Durkan: She polled at 71 percent in Montlake, 72 percent on upper Queen Anne, and 69 percent in Madrona.

Based on Election Night results. For a larger version of the map, click twice on the image.

One last note on the mayoral race: Throughout the fall campaign, Moon faced questions about her ability to earn the votes of supporters of social-justice activist Oliver (and even Oliver’s vote). Overall, it appears that Moon did overwhelmingly win Oliver voters. Moon had bigger improvements between the primary and general in precincts with a lot of Oliver voters. No other factor was more predictive of Moon’s ability to add new voters.

However, Moon also clearly lost some Oliver supporters. Moon’s vote share in this election lags the combined Oliver+Moon primary showing in several neighborhoods, including Columbia City and Capitol Hill. Surprisingly, it also lags that figure in upscale progressive neighborhoods like Madrona, Leschi and Lakewood. Indeed, some of Oliver’s higher-income supporters may have flipped to Durkan. Combined with overwhelming support of suburban-style voters in areas that had been strong for the primary’s fourth-place finisher, Jessyn Farrell, this was enough for Durkan to rack up a healthy margin.

Ultimately, it appears that Durkan’s appeal to middle- and upper-income Seattleites – a solid majority of the electorate – was obscured by the crowded primary. It is now much clearer.

City Council Position 8

Back in August, Jon Grant’s chances against Teresa Mosqueda didn’t look good. Grant, a former executive director of the Tenants Union and an ally of Socialist Alternative City Councilmember Sawant, trailed Mosqueda in the primary, 32 percent to 27 percent. I argued that Mosqueda, whose voters skewed less lefty than Grant’s, was well-positioned to pick up the lion share of center-laner candidate Sara Nelson’s 21 percent. I summarized the race as possibly competitive – which I thought was generous.

Then, on Oct. 16, The Seattle Times decided to make things interesting. In a surprise move, the paper’s editorial board endorsed Jon Grant. The paper – widely held as a guidepost for older, more upscale voters prevalent in Seattle’s center – had endorsed Nelson in the primary. The shockingly dissonant endorsement endangered Mosqueda’s ability to cleanly wrap up the center-lane vote.

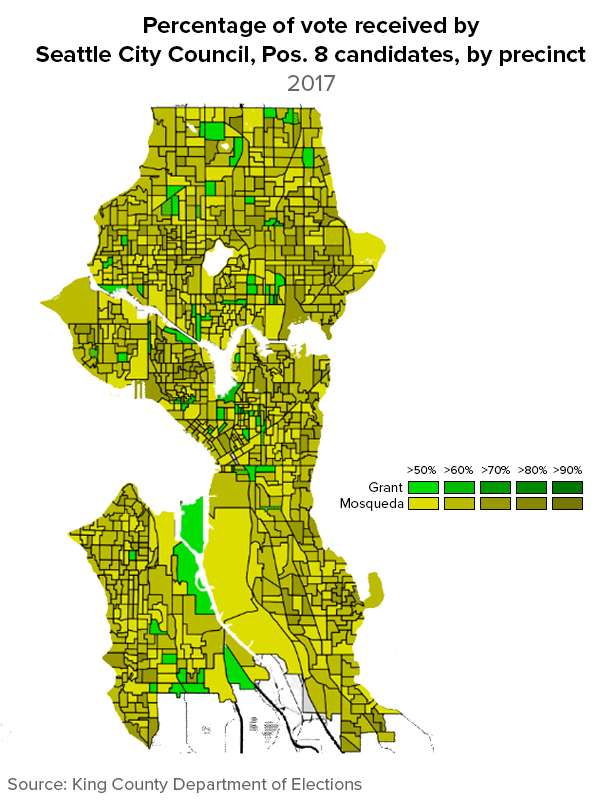

Based on Election Night results. For a larger version of the map, click twice on the image.

Suddenly, it looked like Jon Grant might be able to convert Seattle moderates — at least until Election Night returns blinked on, showing Grant trailing Mosqueda by 23 percentage points.

Here’s the thing, though: The Times endorsement actually did help Grant win a lot of moderates. You can tell by looking at his worst neighborhoods. Most left-lane candidates like Grant have bottom-basement performances in wealthy, centrist neighborhoods like Laurelhurst. But Grant’s performance in Laurelhurst (31.6 percent) was only his third-lowest. His worst were in Madrona (29.8 percent) and the diverse Rainier View community (31.1), near Skyway. Republican-leaning Broadmoor (33.0) wasn’t even in Grant’s top-five worst results.

It’s hard to imagine the Times’ endorsement wasn’t a major factor. Grant’s 33 percent in Broadmoor was a huge improvement over his primary showing of 3 percent. This pattern was reflected in other center-lane strongholds. In Magnolia’s Briarcliff neighborhood, Grant leaped from 10 percent to 35 percent. In Laurelhurst, his 11 percent primary showing nearly tripled. Without the Times’ nod, Grant almost certainly would have lost by more.

Grant’s biggest challenge was that Mosqueda won quite a lot of lefty precincts. On Election Night, in fact, Grant was trailing in all 101 Seattle neighborhoods I tracked. Gains in late ballots will likely end up flipping a few, namely Georgetown (48.7 percent on Election Night), and possibly Broadway (46.5 percent) and/or South Lake Union (45.7 percent). But Mosqueda’s showings were still impressive in these neighborhoods, where Grant needed to rack up big margins. Indeed, it’s more than a little curious to see Grant – who was also endorsed by The Stranger and Seattle Weekly – trailing on Capitol Hill.

Ultimately, Grant won quite a few centrist votes that, in August, would have been presumed as off-the-table for him. Like Moon, his problem was with swing voters who fall between the left and center lanes. Especially in upscale areas like Madrona, they broke heavily against the anti-establishment left.

Steady as it goes

This was a bad year for left-wing populism in Seattle. Two credible left-lane candidates mounted energetic challenges for open seats. They lost in small landslides. While their supporters may point to structural disadvantages – name recognition, money and head starts – these disparities aren’t new to campaigns.

Despite the rough showing, any eulogies for socialist Seattle and progressive Seattle are more than premature — they’re silly. Both Mosqueda and Durkan were strong, well-resourced candidates with considerable appeal to voters outside the center lane. Reading this election as a rejection of lefty politics neglects a less flashy, more likely hypothesis: Seattle voters simply preferred the other candidates. There is no reason to believe compelling left-lane candidates won’t win in future years.

On the other hand, though, this is also a wake-up call for some on the populist left. Even in the midst of national tumult and local growing pains, Seattleites are sometimes fine with staying the course.