The halls of the University of Washington’s ceramics and metal arts building is abuzz with new students embarking on a new school year. But for some, the building feels empty.

Professor Emeritus Akio Takamori taught in the building for 21 years and — after his retirement in 2014 — made frequent visits to reconnect with colleagues and students. For the first time in 24 years, Takamori will not be returning to the building.

“Akio was one of the leading figures in contemporary ceramics,” says Jamie Walker, director of the school, pointing to a bulletin board with several pictures of his late colleague.

“But he never wavered in his commitment to teaching. He would work with all levels of students. He took teaching seriously and it was a job that he loved.”

In addition to teaching at University of Washington for over 20 years, Takamori was an internationally renowned artist, known for his ceramic figurative work that portrayed subtle-but-expressive renderings of the human form. Still in the midst of a prolific career, Takamori died of pancreatic cancer at age 66 in January of 2017.

Takamori was born in Nobeoka, Japan, the youngest of three children whose parents operated a small clinic. Years later, Takamori would draw inspiration from his childhood growing up in a community struggling to rebuild after the devastation of World War II. As a child, Takamori witnessed the full spectrum of humanity, from red-light district workers seeking medical care in his parent’s clinic to artists who frequently stayed at the Takamori home.

Takamori joined the arts club in high school and studied art in Tokyo. He later worked as an apprentice production potter in Koishiwara, Japan, where he honed his skills by making thousands of individual teacups and everyday pottery ware. It was during his apprenticeship where he met Ken Ferguson, head of the ceramics program at the Kansas City Art Institute, who was visiting the pottery factory while touring Japan. Ferguson was drawn to Takamori’s skill and encouraged him to pursue graduate studies in the United States.

“[When you see his work] you can see Akio painting, it’s dripping, it’s an instant mark, you can’t think twice,” says his student Yuki Nakamora, University of Washington class of 1997. “Akio worked really fast, and that speed and breath you can sense in his brush mark.”

Takamori’s work began to garner international attention in the early 1980s, when he began painting sensual human bodies on ceramic slab vessels. The physical marks of his brush strokes possessed the bold quality of Japanese calligraphers, with marks both large and small holding a sense of swiftness of intention. This unique style would become the hallmark of his future work.

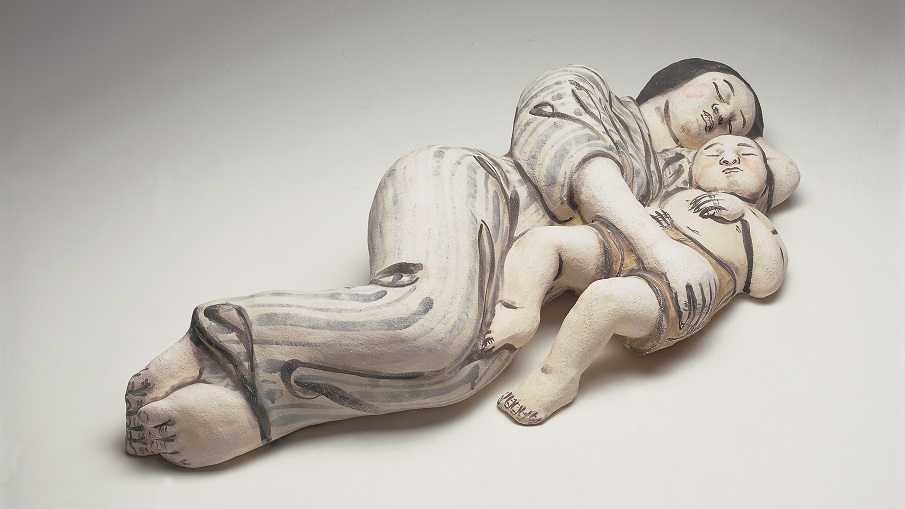

In the mid-1990s, Takamori’s work evolved from slab vessels to stand alone ceramic figures, often referencing memories of village life in Japan. Through the simplicity of their poses and gestures held transcendent universal qualities – humble figures rendered with an earthbound weight and mass.

“Takamori’s renderings of the human form had a genuineness to it,” said Akio’s colleague and friend Patti Warashina, University of Washington ceramics professor emeritus. “When you look at his work, there is a tenderness that has a universal appeal.”

He created figures of people squatting, sleeping, older siblings carrying younger siblings, people standing in quiet repose with large feet firmly rooting them to the ground.

Takamori’s final show “Apology/Remorse” was shown at the James Harris Gallery in February, one month after Takamori died. Gallery owner and friend James Harris says Takamori was inspired by the contemporary political climate to explore the act of apology and state of remorse as it relates to gender and power. Renderings included kneeling Japanese CEOs and placing male heads on the idealized versions of a woman’s body, the Venus de Milo.

For Seattleites, Takamori’s most visible work is a group of larger-than-life figures at the corner of Westlake Avenue North and Denny Way in front of the Whole Foods Market.

Walking around sculptures, Warashina said she was surprised at the resilience of the materials to the outdoor elements.

“It’s very clean, and the aluminum and enamel hasn’t cracked,” she said. “It’s amazing.”

Takamori may no longer be here, but his works of art remain and they embody a lifetime of reflecting on what it means to be human.

This story originally appeared on KCTS9.org.