This story originally appeared in Hakai Magazine.

Coleman Byrnes leads our small team of four through the rainforest of Olympic National Park in Washington State. Where the trail turns muddy, we find a drier alternate route above a border of sword ferns and take special care crossing the slippery boardwalks and prostrate logs. The late-morning sun filters through the canopy, melting some patches of ice and leaving others to crunch under our boots. The forest answers back with the trilling staccato of a tiny Pacific wren.

Byrnes is a former fisheries technician with the US Army Corps of Engineers who lives with his partner, Sue Nattinger, in the nearby rural community of Joyce on the Olympic Peninsula. Their 2.2-hectare property even came with two coho salmon streams. “That’s why I bought it,” he says. “I didn’t even look at the house.”

He is unhurried and deliberate on the trail, seizing the opportunity to chat about everything from climate change to the US presidency to the state of journalism. “If you were on a deserted island and wanted to be mentally stimulated, you’d want Coleman with you,” remarks his friend Bob Phreaner, a retired Philadelphia dentist who moved to the Olympic Peninsula for the biodiversity and temperate climate.

Nattinger is a medical lab technician and accomplished hiker who first climbed 2,429-meter Mount Olympus at age 17—and returned 11 years later with her 10-week-old child in a front carrier. She walks mostly in silence, wearing a cochlear implant due to a hearing impairment. I speak loudly and deliberately. “I’m able to identify some birds by their songs or calls, as long as they’re close or loud enough for me to hear,” she says. “I compensate some by being more attentive to visual cues.”

After close to an hour, we reach gothic stands of Sitka spruce and begin a 60-meter scramble down to the Pacific Ocean, securing our feet against the exposed roots and grabbing ropes to arrest our descent. “It hurts my knees coming back up,” confides Byrnes, staring down the precipice. “That’s what will stop me from doing this.”

At trail’s end, we punch through the understory of salal, an evergreen shrub that grows thick on the coast. Marine buoys hanging from tree limbs mark the entrance to Shi Shi Beach, a magnificent arc of shoreline pounded by the incessant surf. The cliffs of Cape Flattery are just around the corner to the north, the most northwesterly point in the contiguous United States and home to the Makah Tribe. A monolithic line of rocks known as Point of Arches—a National Natural Landmark and more than twice as old as the nearby Olympic Mountains—forms the southern bookend.

You could not ask for a more life-affirming place in the Pacific Northwest—yet death is what brings us here on this crisp winter day.

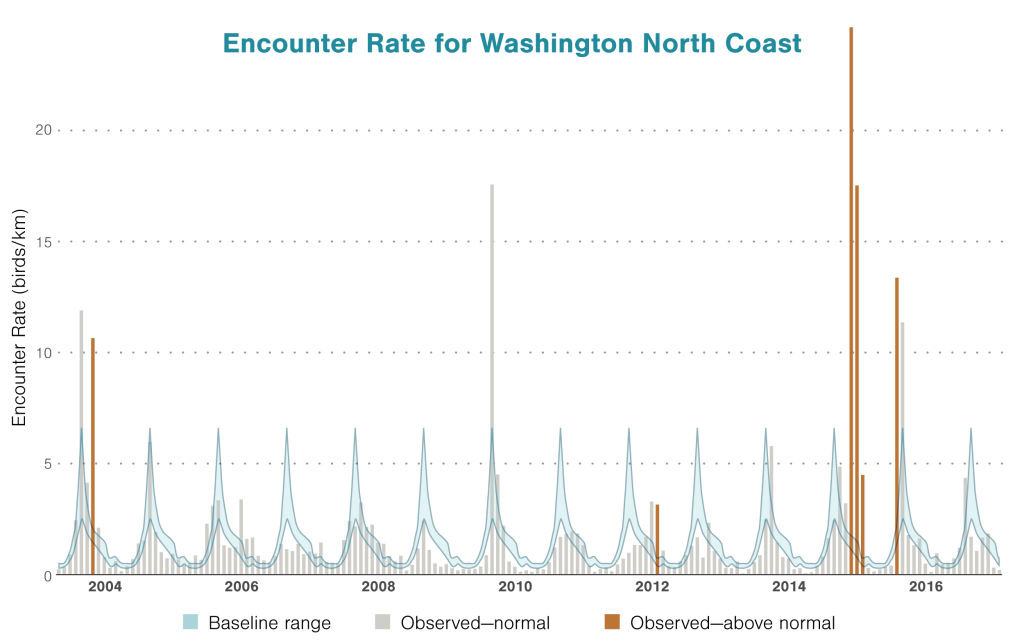

Byrnes, Nattinger, and Phreaner are among about 800 participants who conduct coastal beach patrols for seabird carcasses from Mendocino County in Northern California through Oregon and Washington (bypassing British Columbia, which has its own beached-bird program, but shares data and employs the same methods), all the way to the Bering Sea in Alaska. Since its creation in 2000, the Coastal Observation and Seabird Survey Team (COASST) has documented more than 60,000 carcasses representing 180 species on almost 450 beaches. This sort of baseline information helps researchers track long-term trends influenced by human or natural causes, and is critical for comparison against the number of birds by species associated with, say, a natural die-off, an El Niño climate event, or an oil spill. That’s exactly why Phreaner enlisted as a volunteer: he’s worried about the increased movements of petroleum products through the Salish Sea. “Accidents happen,” he says. “I’m concerned about the consequences of oil spills.”

As we proceed down the beach, Byrnes allows that he is coming down with a cold and didn’t bring enough warm clothing. He wears a wool sweater and a colorful chili pepper-themed hat, and drapes a pair of Pentax binoculars around his neck. I loan him a fleece sweater on which I had spilled some leftover Riesling while packing up this morning. Today, the brace of ocean spray has competition. “Every once in a while I get a sniff of wine,” he says deadpan. “Not bad.”

Byrnes and Nattinger normally bring along their two dogs to help sniff out the deceased at two other COASST locations—Twin River and Shipwreck Point—but national park rules prohibit pets on Shi Shi Beach. We walk southward near the high tideline, eyes scanning like radar for evidence of unmoving beaks and wings. A creamy layer of sea foam catches us off guard. I scramble onto a clump of rocks pitted by boring clams, while Byrnes gets his feet wet. “Oh jeez, he doesn’t watch the surf,” Nattinger remarks. “Too busy looking for birds.”

She strikes out ahead of us and makes the first discovery—a glaucous-winged gull wedged between the drift logs. “No breast or head,” Byrnes observes. “Probably an eagle kill, everything’s eaten.” Phreaner confirms: “That’s pretty clean. Nothing there for the invertebrates to eat.”

The gull carcass is photographed and assigned a color-coded tag so it won’t be counted twice by other COASST volunteers, then left on the beach to be scavenged by everything from bears to sand fleas. After all, dead birds are very much a part of the ecosystem.

Today’s small, dedicated team is the grassroots component of a program founded in academia, at the University of Washington in Seattle. Julia Parrish is a professor in the School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences and got the idea for COASST while researching seabirds on Tatoosh Island off Cape Flattery. As she watched common murres and other newly fledged chicks float ashore dead, she wondered if the same thing was also happening on the mainland and elsewhere along the coast. The problem: researchers alone lacked the numbers to cover such vast stretches of coastline. The solution: enlist an army of volunteers, provide them with five hours of basic training in documenting, identifying, and photographing birds according to protocol, then turn them loose.

Parrish observes that casual beachgoers often blame humanity for seabirds washing ashore. Trained volunteers come to learn that while oil spills and fisheries do kill, natural causes such as bad weather, post-breeding mortality, migration fatigue, algal blooms, and lack of food are far deadlier. Birders with vast experience are less naive. “All death and change is not traceable to some person doing something nefarious,” Parrish says. “It’s easy to document that 50 to 75 percent of birds that we see dead on the beach worldwide die of natural causes. It’s just the cycle of life. It’s always been that way.”

She boils the seabird deaths down to three patterns of change: cyclical (or seasonal), including anticipated post-breeding mortality and winter kills; catastrophic, such as short-term increases in ocean temperatures resulting in shifts in prey availability and large-scale mortalities; and chronic, a subtle shift that can be hard to measure, but includes pervasive influences such as climate change. “The three Cs together create what we see at any one time,” she says. “The fun mystery … is to tease apart how much of what you experience at any one instantaneous moment is due to each of those overlapping kinds of forces.”

During 17 years as a COASST volunteer conducting monthly patrols on Shi Shi Beach, Byrnes has discovered that the largest bird mortalities start in late August and continue through December, a period when young birds are leaving their nests and coping with winter weather. “They’re learning and a lot of them get weeded out,” he says, adding that in late spring and summer there are hardly any deaths. The birds overwintering off Shi Shi Beach, such as loons and scoters, are migrants from nesting grounds in Alaska and Canada in search of prey and open water. Come spring, they migrate north again.

Some days, volunteers get skunked during their beach patrols—which, for the record, is a good thing. Other times, birds come ashore in shocking numbers. On December 28, 2014, for instance, Byrnes and his crew recorded 184 dead Cassin’s auklets, stubby gray burrow-nesting seabirds, on Shi Shi Beach. “We ran out of tags and time and started photographing them in large batches,” he recalls. The event was part of a larger-scale auklet die-off extending south to Oregon and north to Vancouver Island attributed to the sudden unavailability of krill and a particularly nutritious species of copepod, both small crustaceans.

Only once has Byrnes discovered an oiled bird on Shi Shi Beach, the suspected victim of a fishing boat pumping its bilge water. There are fears that could change for the worse. Controversial projects such as Kinder Morgan’s pipeline expansion in Burrard Inlet near Vancouver are expected to increase oil tanker traffic sevenfold in the international waters of the Salish Sea and heighten concerns for seabirds despite double hulls and tug escorts. It all underscores the need for COASST’s vigilance. “As traffic increases, will we see increased volumes of oil birds?” asks Parrish, noting a spill is inevitable.

A short distance down the beach, Nattinger waves at us excitedly. Could this be more than the tattered remains of an ordinary gull? We hurry along with high expectations and find her using a piece of wood to pry up a larger log hiding a prized seabird. It is an adult Laysan albatross. “You’re lucky,” Byrnes says to me. “This is a really rare find.”

Nattinger spreads the bird out on the sand for better inspection. “My goodness, look at those honkin’ wings,” she says. The Laysan is a long-lived bird that roams the Pacific on a wingspan of about two meters. One female—Wisdom—banded in 1956 at Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge northwest of Hawai‘i is considered the world’s oldest documented wild bird at a minimum age of 66. She gave birth in February to the latest of the estimated 30 to 35 chicks she’s raised over six decades. The species is rated near threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and is found on Shi Shi only once every few years.

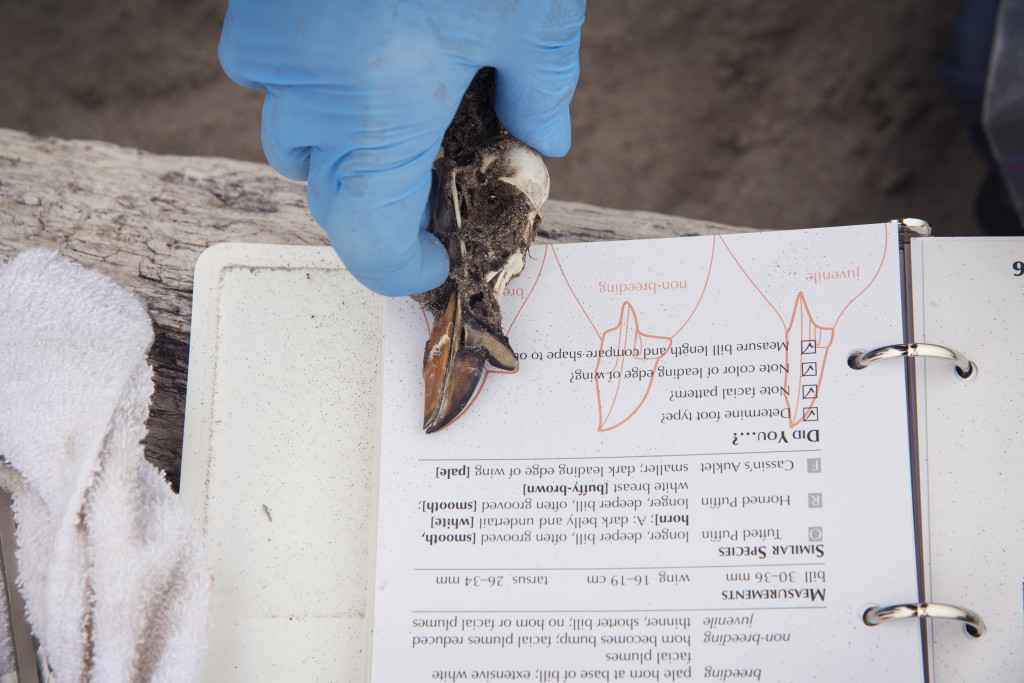

For times like this, COASST volunteers carry a special sturdy, water-resistant field guide, Beached Birds, which offers tips on identification and measurement, as well as practical advice such as tying back one’s long hair to prevent contact with a potentially diseased carcass. Photos are sent to COASST for official species verification.

The team follows protocol by using calipers to measure the bill, the wing cord (the distance from wrist to longest feather tip), and the tarsus (lower leg bone). The badly decomposed carcass is fragile, barely holding together, and the conversation gets tense between Nattinger and Byrnes during one measurement. “You’re not even up to the end,” she admonishes. “I am at the end!” he insists.

When it’s time to move on, I confidently take the lead in hopes of finding something first—only to walk right past the gray feathers of a northern fulmar camouflaged in beach grass near Point of Arches. Tags on the carcass denote it was first recorded November 29, 2016, at about the same location. That makes it an unusual find, since birds tend to get recycled quickly. “When you’re in Alaska, thousands of these follow the fishing boats,” Byrnes says. The gull-like bird is not always a mooch, having the capability of plunging an impressive several meters below the surface for squid, fish, and crustaceans. Admire at a distance: both nesting adults and young can spit a foul-smelling oil at intruders.

It is now late afternoon and time to retrace our steps. Byrnes has visited Shi Shi Beach close to 250 times, and remains as awed today as the first time he visited 52 years ago. The place is bustling in summer, having been featured in magazines around the world. Today, it attracts only a smattering of visitors, including an ambitious couple of surfers who have lugged their boards and backpacks through the forest. “Twilight on the beach on a winter day,” Byrnes says with a final glance. “I just love it.”

Nattinger and Phreaner scale the bluff first and continue ahead to the trailhead parking lot in the growing darkness. I stay back with the slower-moving Byrnes—a man who was given his first cellphone only recently, who still doesn’t own a credit card, and who, today at least, carries a flashlight that emits the beam of a firefly. I give him my spare and together we navigate the forested obstacle course.

Byrnes lives by the motto, “Any day indoors is a day wasted,” and embraces his volunteer role. “I like the science and contributing to big data sets. If a lot of animals are going to be saved, you’ll have to know what’s going on,” he says. He also pays a price for dedication: the sheer hours, the body aches, the vehicle expenses, and, who would have guessed, the need to offset one’s carbon footprint. “I pay at least $10 every trip to a group that plants trees,” he says.

It’s that kind of commitment that makes the information collected by COASST volunteers so valuable. “These are the people on the ground that know their beaches far better than I do,” Parrish confirms. “What we all do together is citizen science. It’s a strongly linked team sport, everyone with different roles.”

The beach observations are the foundation for a program destined to benefit bird populations over the generations, providing reliable information against which scientists can detect future population changes, some attributed to factors we cannot yet imagine.

Ultimately, the data will outlive the data collectors. “It will be a shame the day I have to stop coming here,” Byrnes says. “You have to know your limitations as you grow older.”

As we press on, the rainforest absorbs the last faint sounds of the distant surf. Somewhere out there in the cold darkness on an unsympathetic sea a bird is dying, its carcass to be washed ashore and given new meaning by those who quietly observe and report.