After more than two decades of bickering among bicycle and pedestrian advocates and business interests, Seattle appears to have finally settled on a route for the “missing link” — the controversial final 1.4 miles of the city’s beloved Burke-Gilman Trail. But the fight is not over yet.

At a press conference last Tuesday, Mayor Ed Murray announced that the trail will be completed along Shilshole Avenue South through Ballard. The final environmental impact statement will be published in May, he said, and construction is expected to begin in 2018.

“Today’s major announcement ends 20 years of disagreements, lawsuits, studies and counter studies,” Murray said.

City Councilmember Mike O’Brien said that this route was the result of “a really strong community consensus around how to complete this missing link, how to build this trail in the way that would be safest for everyone.”

But Josh Brower, an attorney with Veris Law Group who has represented several businesses and labor groups opposed to the Shilshole Avenue route, said they have not dropped their lawsuit. Since 1996, business owners have argued that constructing the missing link along their driveways would impact day-to-day operations and increase the risk of collisions between trucks and trail users.

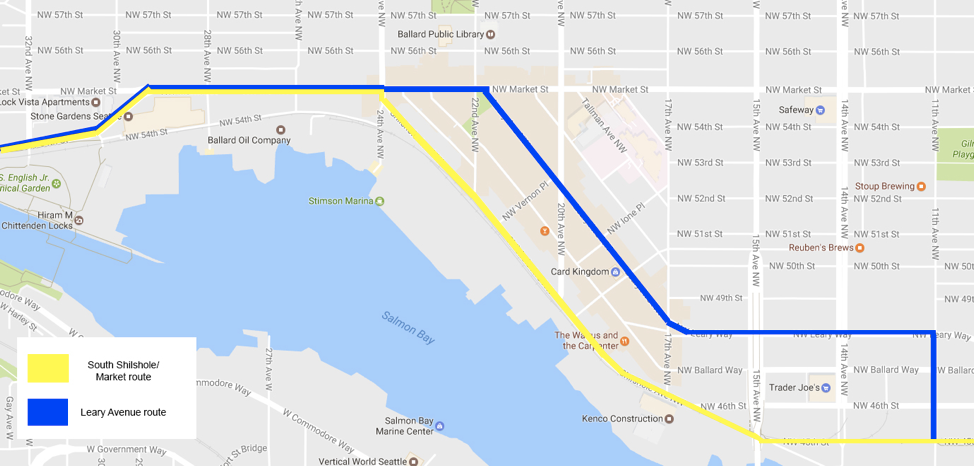

The selected route follows Shilshole Avenue South and Northwest Market Street before connecting to the other end of the trail by the Ballard Locks. Business groups prefer a different route along Leary Avenue.

The Leary route would cross the fewest driveways and loading docks. According to the draft environmental impact statement, the South Shilshole route crosses 41, the Ballard Avenue route crosses 42, and the Leary route crosses 33.

But the South Shilshole route crosses the fewest intersections, making it the preferred route for cyclists. The South Shilshole route crosses four intersections, the Ballard Avenue route crosses 16 intersections, and the Leary route crosses 14 intersections.

Kevin Carrabine, founder of the Friends of the Burke-Gilman Trail, said at a press conference in January that many businesses already coexist with the trail and that industrial businesses in other cities have found ways to welcome pedestrians. He cited a concrete company in Vancouver’s Granville Island that holds an annual open house for the local community.

Groups represented by Veris Law Group include the King County Labor Council, the Seattle Building and Construction Council, the International Operating Engineers Local 302, and the Teamsters Union Local 174.

Michael Gonzales, of Teamsters Local 174, said building the missing link in the industrial area of Ballard puts cyclists at risk of collisions with the concrete trucks, delivery trucks, and other large vehicles that are constantly entering and leaving waterfront businesses.

“We just see a real disaster when you mix freight trucks and pedestrians,” Gonzales said. “There’s going to be an accident. It’s just not safe.”

There are also concerns about the cost of the project. According to a 2010 estimate, construction of the 1.5-mile missing link is expected to cost $14 million, including design and construction. At a sustainability and transportation committee meeting last month, representatives of the Seattle Department of Transportation said they hadn’t produced an updated cost estimate since then.

According to page 230 of the city’s Capital Improvement Program, SDOT has budgeted nearly $31 million for the missing link between 2017 and 2022. The Westlake protected bike lane, a 1.2-mile lane that opened in fall 2016, cost just $6.1 million.

Brower said the project’s high price tag raises questions about race and equity in the city’s budget.

Individuals and community groups sent letters to SDOT during the public comment period for the draft environmental impact statement. Two of these groups were the Urban League, which supports African-American and underserved communities, and Centerstone, which serves low-income communities.

Centerstone CEO Andrea Caupain and Urban League CEO Pamela Banks both urged SDOT to devote more funds to bicycle facilities in south and southeast Seattle.

“It seems to me that most of the bicycle facilities and infrastructure we are developing is geared toward the north end bicycle rider and not in communities of color,” Banks wrote. “I implore you to look at a less costly alternative in Ballard and to more equitably spend bicycle funds throughout Seattle.”

Mark Mazzola, SDOT’s environmental coordinator, wrote in an email that the missing link project was included in the equity analysis in the 2015 Seattle Bicycle Master Plan. This analysis used factors including age, race and ethnicity, poverty level, and automobile access to assign equity scores to different parts of the city.

“The purpose of the Missing Link project is to complete the last leg of the Burke-Gilman Trail, which serves a large portion of Seattle and the region as a highly used non-motorized transportation and recreational facility for people of all ages, abilities and backgrounds,” he wrote.

Mazzola also said the 2016-2020 Seattle Bicycle Master Plan includes recommendations for several projects in South Seattle, including protected bike lanes and neighborhood greenways.

“SDOT’s goal is to achieve zero areas lacking bicycle facilities by 2030,” he wrote.

At last week’s press conference, Mayor Murray said, “Because of this agreement, we will now begin design, and about this time next year we will break ground and make this project a reality.”

But once the final environmental impact statement is published, Brower said, industrial groups could be back in court.