Seattle’s hills can be daunting for anyone, sometimes even for drivers. And then there are all those construction sites that may push walkers or those in wheelchairs into the street.

A mapping project based out of the UW Department of Computer Science and Engineering Taskar Center for Accessible Technology is hoping to help people with mobility issues get around the city better. AccessMap, which launched this month, is an online travel planner that helps users find accessible routes in Seattle. It lets them customize their routes to avoid obstacles like steep hills, sidewalks without curb cuts, and construction sites.

It’s already starting to make a difference.

Clark Matthews, a filmmaker and disability rights advocate, said AccessMap has helped him navigate Seattle in his manual wheelchair since his recent move here. He said he’s used sidewalks and public transportation in cities like Philadelphia, New York, Boston and Baltimore, but Seattle has presented unique challenges.

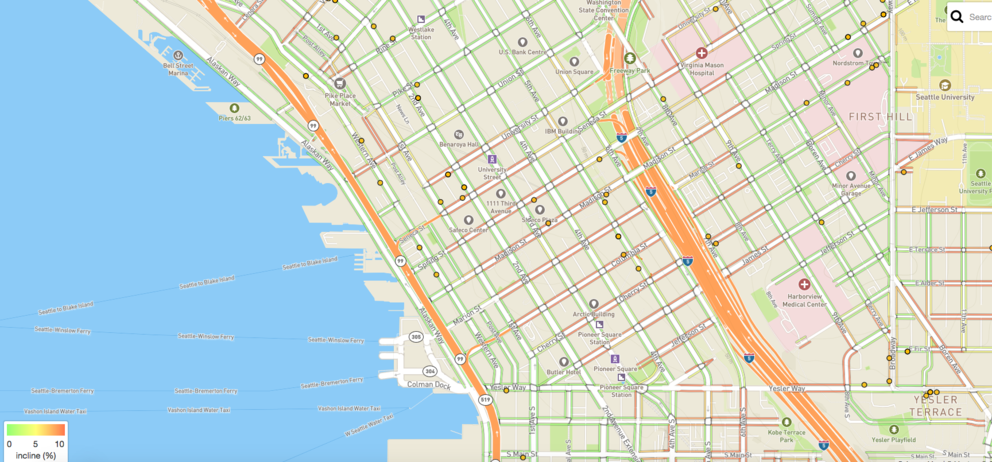

“This is the first time in my life where I literally can't push myself to the bus stop because the sidewalk is just too steep,” Matthews said. “Thankfully, whenever I need to head somewhere new, I now can always make sure to check for any red streets on the map before I go and know what exactly I'm rolling into.”

The project seeks to fill a gap in online navigation services like Google Maps that use street data to suggest walking routes for its users.

“We don’t currently treat pedestrian ways, like sidewalks or paths, as an actual transportation network,” said Nick Bolten, an electrical engineering Ph.D. student who leads the project. “That’s the big shift that we’re pushing for.”

Bolten and three other students began the project at a Hack the Commute hackathon competition in 2015. At the hackathon, students were paired with experts in a field that could benefit from using city data. Bolten spent the hackathon at the accessibility table, where he and the other students built an early version of AccessMap.

They won the hackathon and received an outpouring of support. That summer, they participated in the eScience Institute’s first Data Science for Social Good program, which supports data scientists and other students interested in using data to address problems in the community. The team spent the summer cleaning up the city data they had used at the hackathon.

The following summer, they were invited back to the Data Science for Social Good program. They reached out to people involved with OpenStreetMap, a collaborative map built from contributions by users. Inspired by OpenStreetMaps’ format, the team created OpenSidewalks, which uses the same open source format but focuses on mapping sidewalks instead of roads.

“OpenStreetMap is kind of the Wikipedia of maps,” said Jess Hamilton, a landscape architect with Urban@UW who contributed to the OpenSidewalks project. “It looks a lot like Google Maps, but it’s all open source. It’s got this really flexible structure so that people can add what they want.”

AccessMap currently combines a map base from OpenStreetMap and the sidewalk data from the city. Users can customize maximum uphill incline, maximum downhill incline, and whether they want to avoid barriers like construction zones or curb ramps.

Sumit Mukherjee, a Ph.D. candidate who works on the project’s navigation elements, said customization makes the map useful for a wide range of pedestrians. For example, people in automated wheelchairs may be able to take steeper routes than those in manual wheelchairs.

“Not all disabled people have the same limitations,” Mukherjee said. “A lot of times, if you ask people to rate obstacles like high elevation, low elevation, curb ramps, and construction sites, it’s a hard thing to give a number to.” To address the difficulty of rating those obstacles, Mukherjee said he hopes to develop a more automated routing app for pedestrians. He noted that some routing apps use a driver’s average driving speed to predict the estimated time of arrival or use past preferences to suggest a route. Mukherjee said a pedestrian app could involve measuring a user’s trip time and collecting survey data after each trip.

“We want to be kind of like Amazon,” Mukherjee said. “In Amazon, after you’ve looked at a few things, they automatically start predicting what you want to buy. We want to use similar technology, but for routing.”

Anat Caspi, director of the Taskar Center, also became involved with the project at the hackathon, where she staffed the accessibility table and told interested students about the obstacles people faced in Seattle.

Matthews said using a site like Google Maps can be time consuming because he has to make his own adjustments to suggested routes.

“I never get to just look something up and go,” Matthews said. “Unless an app is specifically designed for wheelchair users, it never ever takes into account that not everyone gets around the exact same way.”

Caspi said she was surprised by the lack of sidewalk data that city governments have available.

“I was sure cities would have this. Otherwise, how do they make decisions like where to add a curb cut?” Caspi asked. “There’s very few data points they use to make these kinds of decisions, which makes you question how tax dollars are being used and how projects are prioritized.”

Bolten said open source sidewalk mapping could help city governments avoid the costs that come with revaluating sidewalk data. In October 2015, the City of Seattle was sued for its lack of properly maintained curb cuts. Bolten said having an open source data set like the one created through OpenStreetMap could help the city stay up to date using information provided by the public.

Bolten and Caspi hope to expand the project to 10 cities around the country where there is already a strong OpenStreetMap community. Portland, for example, uses open source data for its online trip planner serving bikers and pedestrians as well as transit users.

Hamilton said the project has exposed her to a problem she hadn’t thought about before.

“Our whole country has largely been designed around cars, and that continues to be the case even with our digital maps,” Hamilton said. “There are plenty of people who don’t drive, and this big segment of the population is being excluded. It’s astounding how much is overlooked.”

Caspi said this technology could help pedestrians with or without mobility limitations. For example, people with strollers might want to avoid routes without curb ramps.

“Google Maps has trained us to minimize the amount of information we ask for about the environment,” Caspi said. “For us, it’s presumably low hassle to circumvent these things when we meet them on the ground. For someone with a mobility impairment, it’s a much bigger cost, but it doesn’t mean that there’s no cost to all of us.”

—

This series is made possible with support from Comcast. The views and opinions expressed in the media, articles, or comments on this article are those of the authors and do not reflect or represent the views and opinions held by Comcast.