Late last month, the Department of Justice announced it's cutting ties with the private prison industry. In the coming years, the department will take control of the 14 federal prisons currently managed through contracts with private companies, none located in the Pacific Northwest. But a subsequent announcement has regional implications: following a letter from Sen. Bernie Sanders and Rep. Raul , Grijalva, the Department of Homeland Security may follow the DOJ's lead, and take “detention centers” for undocumented immigrants away from for-profit companies.

That includes the only place where prison corporations operate in the region: the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma.

One might assume the federal government’s announcements are tied to increased tensions between marginalized communities and the U.S. criminal justice system, and the growing appetite on both sides of the aisle for reform. But the stated motive is cold economics: Private prisons aren’t a wise use of taxpayer money.

Private prison companies present themselves as a cost-saving measure, a way to introduce private market efficiencies to the business of storing people in cages. According to a recent report from the U.S. Office of the Inspector General, however, the government is spending an increasing amount on these private prisons, and the results are often shoddy. In addition to the poor treatment of inmates, the report notes these facilities have also played host to “extensive property damage, bodily injury and the death of a Correctional Officer.”

This hard-nosed reappraisal of costs and benefits could also apply to private detention centers, which hold about two-thirds of the country’s detained immigrants. So as officials and policymakers consider whether to cut ties with prison corporations, we present a short primer on the Tacoma facility.

What is the Northwest Immigration Detention Center?

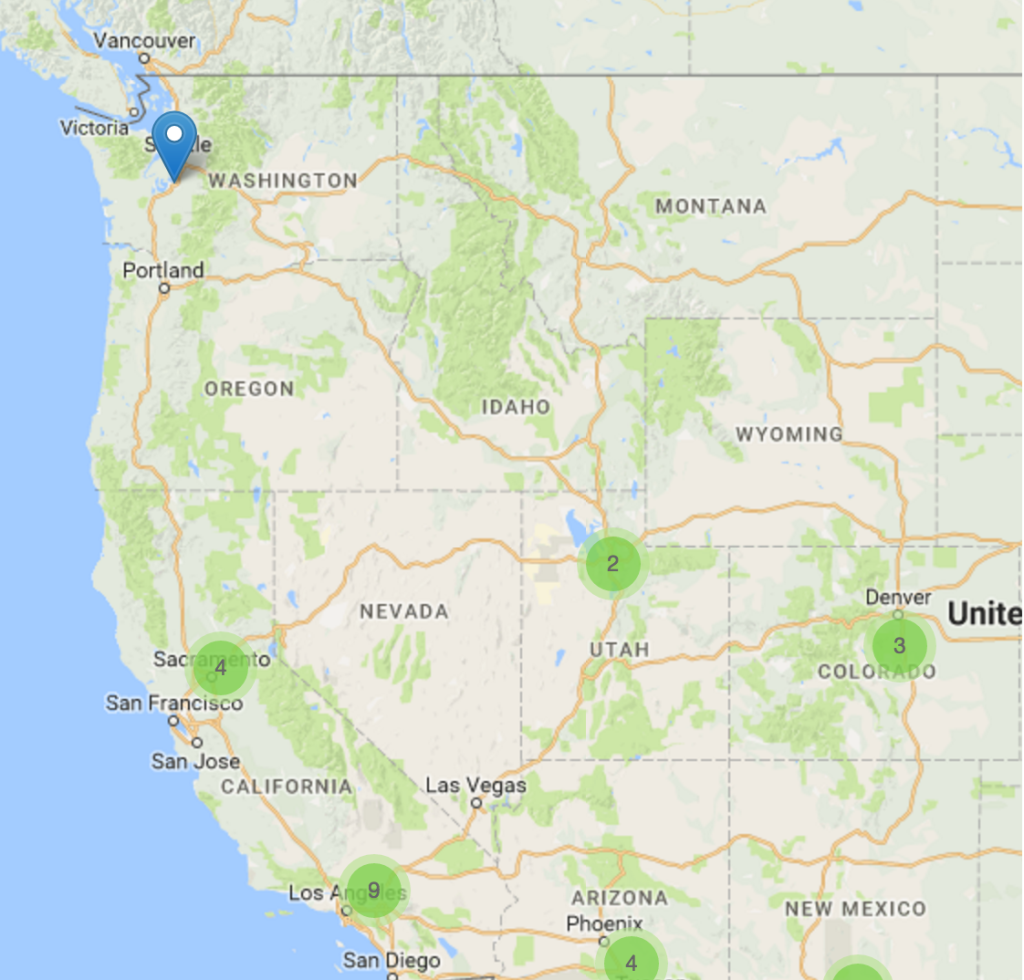

Located directly adjacent to downtown Tacoma — a short walk away from tourist destinations like the Glass Museum — the Northwest Detention Center holds undocumented immigrants arrested in Washington, Oregon and elsewhere in the region. Every month, new detainees arrive while others are deported from the United States.

The center has capacity for almost 1,600 detainees, but head counts can fluctuate. According to a spokesperson for Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), they’re currently holding about 1,500. This puts them among the largest detention centers in the U.S.

The Northwest Detention Center is run by GEO Group, one of the private prison industry's main players. Last year, ICE renewed the company’s contract to run the prison for the next 10 years.

The center generates revenue of nearly $57 million annually, according to GEO estimates.

Why is it controversial?

Activism is the biggest reason people are aware of the detention center, and the reason it usually appears in the media. In 2007, a man held there performed a hunger strike for fear of being sent back home in Yemen, where he would be prosecuted. In 2014, there was a much larger hunger strike by detainees due to complaints about bad food, medical negligence and drawn-out court hearings. Immigrant rights activists also stage frequent protests outside the facility.

“At the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma, Washington, I have witnessed firsthand the exploitative living conditions these detainees face, and have advocated for immediate changes to our immigration detention operations,” said Rep. Adam Smith, who represents the district containing the detention center. Following a visit to the center, Smith has sponsored or co-sponsored legislation to reform the immigration detention system.

Smith told Crosscut that conditions in the facility have improved since 2014, likely in response to the protests and the attention they garnered. The American Correctional Association gives the facility a stellar rating, but there have been complaints from detainees that they are not given enough food or are overworked for nearly no pay.

But beyond conditions at the facility, its very business model is a target for the immigrant rights community. Perhaps most controversially, there is the policy of “bed mandates,” which both Smith and immigration rights activists are dedicated to eradicating.

What is a “bed mandate?”

To understand the little-known "bed mandate" policy, imagine you’re an executive at Costco, dealing with Heinz. In order to save space on the shelf for the company’s ketchup, Heinz needs to guarantee they’ll deliver a certain amount of it every month. Otherwise Costco can’t be sure it’s maximizing profits on that shelf.

Now make that product into people and families, and you have the bed mandate, a guarantee from the federal government to private prison companies that they’ll arrest and deliver a certain amount of people to detention centers, and then pay for them on a per-head basis. If they don’t, they still pay companies like GEO group for the empty beds, so there's an incentive to deliver.

At current time, the national bed mandate is about 34,000, nearly double the capacity of ICE facilities 10 years ago. Given that illegal immigration has recently been dropping to some of its lowest levels in decades, critics of the mandate contend that ICE has been meeting its requirements by detaining people at traffic stops or other such encounters, or by targeting foreign-born, legal U.S. citizens for deportation following minor crimes.

Further, immigrant rights advocates argue that the majority of detainees are not violent offenders, often support families, and do not pose a threat to public safety. Department of Homeland Security officials disagree, saying they have no trouble finding criminals worthy of deportation to meet the bed mandate.

Smith said he believes private companies would not be in the detention center business without the bed mandate, which ensures them a certain amount of annual profit. Similarly, the bed mandate would likely not exist if the feds weren’t trying to lure private industry into the space — again, the assumption being that these companies are saving taxpayers money.

What’s next?

Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson has ordered a review of how his agency can cease using private immigrant detention facilities. There’s no telling how long this may take, but between this and the DOJ’s announcement, the fortunes of private prison companies have already been impacted. Three of the top corporations in the field — Corrections Corporation of America, GEO Group, and Management and Training Corporation — have seen their stocks fall.

A decision to cut ties with private prison companies would be seen as a victory for immigrant rights advocates, who believe profit motives are driving an increase in detainments and deportations. In the past decade, the amount the federal government spends on these actions has roughly doubled to $2.8 billion per year.

However, immigration officials say the system would cost much more in the hands of the federal government. Cutting private management companies out of the field “would be remarkably detrimental,” a senior Immigration and Customs Enforcement official told the L.A. Times.

As the recent announcements make clear, budget considerations — not the civil rights of foreign born individuals — will likely take the fore in coming debates over the private prison industry. In an interview, Smith said he is hopeful there will be progress on this issue outside of the broader immigration reform debate, which has been bogged down for many years.

“While the move to reevaluate the use of privately run facilities is indeed the correct one, this is only the first step towards rebuilding a system that is in dire need of comprehensive reform,” Smith said.