For Tyler Thornton, pears, apples and jetliners aren’t so far apart.

Thornton, now 22, grew up as a fourth-generation orchardist in the remote Okanogan Valley, where his great-grandfather settled in 1904. Now he’s finishing up a summer internship at Boeing and is one semester away from his Bachelor’s in Civil Engineering at Washington State University in Pullman.

“Growing up on a farm is all about problem-solving. You move from one chaos or catastrophe to another,” Thornton said. “I’ve been working through problems my whole life, being around machinery, thinking of innovative solutions to stay in business.”

Thornton said that his teachers in the 1,080-student Tonasket School District, noticing this set of skills, pointed him to engineering as a possible career.

Thornton and Tonasket aren’t alone in making the connection between rural and agricultural skills and jobs in science, technology, engineering and math, often referred to as the STEM fields. A number of school districts and nonprofits throughout the state are increasingly focused on creating stronger STEM education programs and making connections between existing industries and STEM skills in rural Washington.

Many emphasize the natural connection between rural skills and STEM fields. But there’s also an urgency behind the efforts: Rural Washington schools are undergoing a longer-term demographic transformation as many family farms have been consolidated, more migrant farmworkers have arrived, and populations in many towns are aging. Many schools are also short on resources, funds, and even teachers.

That’s left educators to figure out how to prevent their students from being left behind in a changing economy. While jobs connected to STEM subjects have become increasingly common in the state, rural students are often isolated from those opportunities, according to Barbara Peterson, the director of the Northwest Learning and Achievement Group, a nonprofit focused on young people in Washington’s rural school districts.

Strengths and challenges in rural schools

For the 10 percent of Washington’s public school students who are growing up in rural parts of the state, geography can be a blessing and a curse.

In Washington, rural schools have a higher on-time graduation rate for students than the state as a whole — 70.3 percent, compared to 59.8 percent overall. But some rural schools lack the teachers, students, or facilities to support advanced coursework and technology that’s present in larger school districts. If a senior class has six students, it may not make sense to offer AP Calculus AB and BC. Many rural districts are facing a crisis-level teacher shortage; some don’t have wireless internet.

Still, rural students in Washington have access to some of the most fascinating geology and astronomy in the state. They live near some of the biggest engineering projects, like dams and nuclear facilities. And Peterson argues that rural students have often learned problem-solving skills that could lend themselves naturally to careers in STEM fields, if anyone helped them make the connection.

There’s some research to back her up: The results of the first-ever national assessment of technology and engineering skills in the U.S. found rural students earning comparable scores to their suburban peers, and significantly outscoring urban students. A survey that accompanied the test, known as the NAEP, found that many rural students reported learning problem-solving skills outside of the classroom.

For Peterson, this situation poses a question: “If students have had unequal preparation but they could do well in these fields, how do we provide the additional support we need to help them make up for that deficit?”

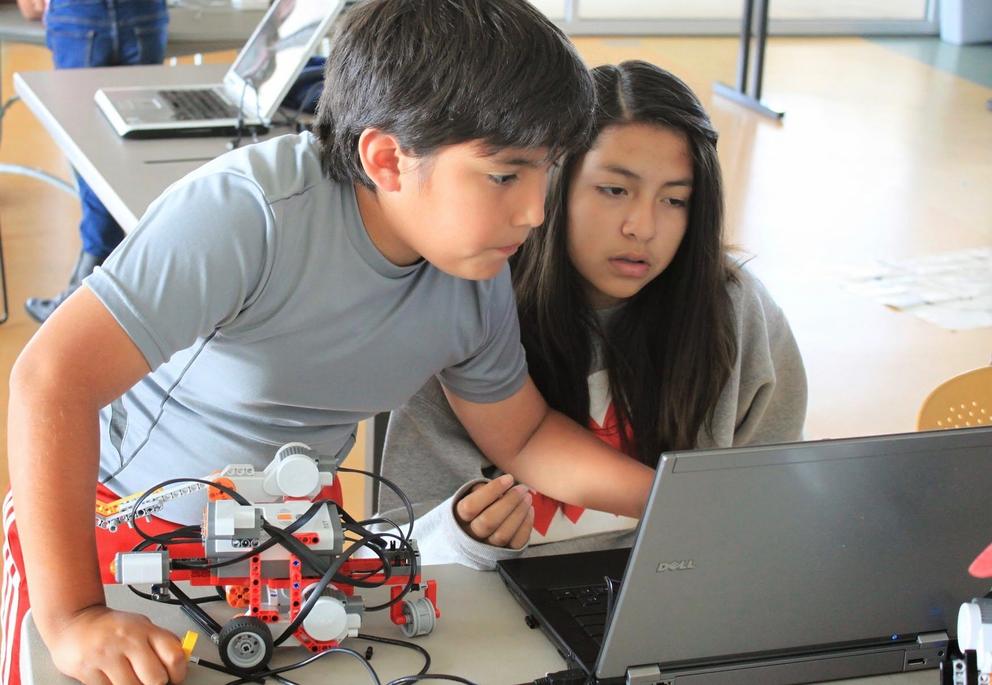

Her approach: Catch students young, offer extracurricular and afterschool opportunities that might get them interested in STEM, and help them see the connections between the problem-solving skills they already possess and fields like engineering. Organizations affiliated with the Northwest Learning and Achievement Group run camps and offer in-school sessions on topics like engineering and robotics.

“We’re trying to flood a group of kids with an awareness of STEM careers, and empower them to work with each other,” Peterson said.

Still, Peterson said it’s important to understand the nuances of rural families’ decisions about education: While there may be more job opportunities outside of rural areas, there is also a fear that encouraging kids to leave for education and career contributes to a rural “brain drain.”

Can STEM careers reverse bran drain?

In 2015, Peterson and a group of colleagues wrote a paper, Rural Students in Washington State: STEM as a Strategy for Building Rigor, Postsecondary Aspirations, and Relevant Career Opportunities. The paper highlights a handful of programs throughout the state that introduce rural students to STEM careers.

Among the other groups reaching out directly to rural students is the Washington State Opportunity Scholarship Program, which offers students scholarships if they are studying high-demand subjects, including STEM, has recruited students from rural districts throughout the state. “Washington is a vast and amazing state,” said Naria Santa Lucia, the executive director of the scholarship program.

Spokesperson Megan Nelson said that for rural schools, an individual counselor who is aware of opportunities like the scholarship program can make a big difference. She said that, as in suburban and urban schools, low-income students face the biggest barriers to higher education and careers in STEM fields.

Lee Lambert, the director of the regional networks for the nonprofit advocacy group Washington STEM, said that his organization is hoping to connect education leaders to businesses and nonprofits throughout the state, including rural areas. He said rural areas are often home to a host of unexpected STEM careers: In Yakima’s apple industry or in old logging towns, there are jobs and opportunities for scientists and engineers and in computer science, he said.

Lambert said Washington STEM hopes that exposing students to these jobs could help inspire them to see new possibilities for themselves, and that connections fostered through the networks might increase educational and career opportunities for rural students.

In her paper on rural students in Washington, Peterson also argues that the growth in freelancing driven by technological changes might also open up opportunities for young people to live in rural areas while participating in high tech fields, thus stemming the brain drain.

Tonasket is one of the districts that has embraced STEM as a path to opportunity for its young people. A federal grant program called GEAR Up, focused on helping low-income students attend college, has supported programs including computer programming and natural resource camps. Several students have participated in a STEM fellowship for high schoolers interested in the sciences. The school has also started a robotics club that has sent several students to a national competition and introduced an engineering class for middle schoolers.

Thornton said that for him, relationships with individual teachers in Tonasket helped guide him toward a career in engineering.

And now, he says, the gap between his rural upbringing and more urban present doesn’t feel like a contradiction. He says he could see himself spending part of his career working at a larger company in a less rural area and part of it in a place like Tonasket.

“I see rural kids as having every advantage,” he said.

—

This series made possible with support from Alaska Airlines. The views and opinions expressed in the media, articles, or comments on this article are those of the authors and do not reflect or represent the views and opinions held by Alaska Airlines.