Susie Lee was fresh out of Yale, preparing for medical school, when she felt the walls closing in. She had majored in molecular biology, with the goal of becoming a cutting-edge reconstructive hand surgeon. Nothing “would rock” more, in her terms. Patients would come to her, and she would return their ability to hold things, to make things. She’d played piano since she was a small girl in North Dakota, she explains. She respected what hands can do.

But the career that had been planned — her immigrant parents had a lab coat embroidered with her name when she was young — lost its allure. When the acceptance letter from medical school arrived, Lee was hit with a sinking feeling. Looking ahead, she saw a progression of pre-determined actions and milestones, none arousing her passion.

“It’s always a bad sign when you say to yourself, ‘Oh, my life is over,’” Lee says. “I’d spent most of my life working to that point, and it was time to look at what it would take to turn the barge around.”

Lee’s road to her current position — CEO and founder of Siren, a dating app that won Geekwire’s 2015 App of the Year — has been full of twists. But in recounting the path behind her and the work ahead, she hopes to make a case for more diversity in the tech world, not only in terms of gender and race, but also background and personality.

Following her decision to forgo medical school, Lee briefly taught science in a New York City public school, and received a master’s from Columbia Teachers College, where she was the recipient of a Carnegie Mellon Fellowship. The work was fulfilling, although the education system felt hopelessly broken to her. It was a transitional period, one to which she can peg a clear ending point: her friend’s invitation to join a ceramics class.

There was something immediately visceral about molding the clay, watching work emerge from the kiln. She kept experimenting, feeling more and more inspired. Art felt like a hobby, not a career path, but her partner of the time encouraged her. Few people spend their lives doing things they actually like, he said.

“That stuck with me,” she says. “The privilege wasn’t just socio-economic. Many people just don’t have a passion like that. It’s a tragedy if you don’t try to pursue it if you have one.”

Lee eventually moved to Seattle, and received a Visual Art Genius Award from The Stranger in 2010, although not for anything related to clay. Instead, her award-winning project attempted to convey empathy and human connection. Called “Still Lives," it used "still life" videos to present elderly people who were near death, showing them starkly and without sentimentality, as one imagines we might see things at a very late age.

It’s this sort of empathy — an attempt to see the world through other people’s eyes — that she believes is sorely lacking from tech culture, and could be the industry’s biggest hindrance.

“Inclusivity matters,” says Lee. “It means you bring the best ideas and experiences to the table, not just homogenized and siloed viewpoints.”

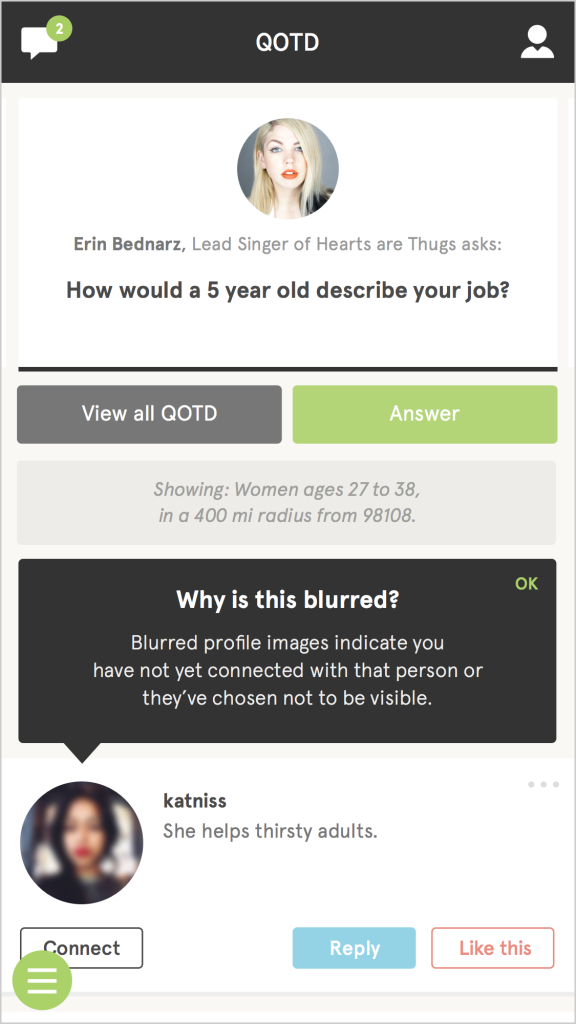

This is the wall Lee hit when she began pitching her app, Siren, to investors. Dating apps, by and large, are tailored to men. They encourage judgments based on appearance, she says, and shallow behaviors and exchanges. So Lee created an app to “radically humanize online dating” by encouraging interactions over imagery, and letting women make the first move.

“Thinking of my partners in the past, I never would’ve found them using these apps people use,” says Lee. “I think a lot of women value things that foster a sense of authenticity. That’s something the market isn’t getting with this approach that’s hot-or-not, literally. If you can make an app that creates meaningful connections between people, that’s the most amazing sort of social sculpture.”

Or to paraphrase at least one investor Lee has met, Siren is a non-starter, “because women who have to control their photos must be ugly and fat, and men won’t want to use it.”

These reactions spring from a bland, cookie-cutter mindset found across the industry, Lee says. The people who create other dating apps often share a similar profile with those who invest in them: middle-to-upper class, largely white, male. This closed loop crowds out ideas not tailored to audiences of that description.

Pitching in this environment is difficult, Lee says. “I think it’s that lack of empathy, where you try to present another point of view. On top of that, as a first-time founder, (venture capitalists) are unwilling to believe a woman can execute on something. Just patronizing. It’s like, motherfucker, I didn’t get on this stage sitting around like a wallflower.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4UijSPj1wT8

The solution is more diversity in the sector. But that doesn’t just mean opening the door for more women and people of color into technical educations, Lee says. It also means rethinking the sorts of education and backgrounds that can add value to the industry.

Lee is an evangelist of the STEAM approach to education, for example, which adds art to the science, tech, engineering and math in more traditional STEM. “Arts, engineering, math, science — none of these fields alone owns creativity. It’s important in all of them.”

“Plus, artists are used to hustling,” Lee says. “You have no money and you make this thing. They’re open to experimentation. Just from a practical business standpoint, having someone artistic means having a point of view you wouldn’t have otherwise.”

Lee admits an artist or non-technical person might not be helpful if, say, you’re creating complex cloud computing systems. But coming up with products for the general public is another matter. Tech can be like architecture, creating a space in which people interact, and “dictating the sort of behaviors you want people to have.” This is what she’s trying to accomplish with Siren, she says.

But it’s an uphill battle. Lee tries to find humor in the overwhelming white maleness of tech. The homogeneity doesn’t end there, she jokes. Attending some industry soirees, the blue button-up dress shirts stretch as far as the eye can see. Everyone’s using the same exact buzzwords, and so many of the interactions are “awkward as shit.” She talks about her attempts to embrace the “sheer weirdness” of it all, to call out “the white elephant in the room” while finding allies — “the ones who actually want to talk about it.”

Her future — and that of the tech industry — hinges on a concept she borrowed from economist and writer Albert Hirschman, she says. In his book “Exit, Voice, and Loyalty”, the author describes the choice people face when an organization, relationship or product is diminishing in quality. You can either check out, or make an attempt to use your “voice” to improve or reform it. The worse things get, the more necessary a choice becomes.

“American culture prefers ‘exit’ – I’m tired of this shit and I’m leaving,” says Lee. “If you’re a woman in tech, around clueless dudes all the time, you might think there’s a better place to use your time or make an impact. Maybe you can just go be a barrista at an island café.”

Lee has chosen to exit before, with advanced degrees to show for it. But she says that if people like her — women, people of color, artists — don’t use their voices to change the tech world, they’ll cede one of the greatest modern outlets for creativity, the place where “digital media can have the greatest impact,” shaping our daily lives. An exit can’t be an option.

---

Throughout the month, Crosscut is showcasing the perspectives and experiences of women within the region’s innovation economy, as well as analysis of the persistent gender gaps within the tech industry. To submit stories and tips, please write editor@crosscut.com.

This series made possible with support from the Washington Technology Industry Association. The views and opinions expressed in the articles are those of the authors, and do not reflects those of the supporting organization.