Can something be simultaneously overrated and imperative to our future? This is the question as global leaders converge on Paris for COP21, a United Nations conference meant to align the world around new climate goals.

Over the next week and a half, representatives of over 190 countries will hash out a new plan to curb the Earth’s rising temperature, which the vast majority of scientists have linked to human activity. But the politics and logistics of achieving this goal are complicated, and for the lay observer, there are a lot of questions.

So as Gov. Jay Inslee, King County Councilmember Larry Philips, and Seattle City Councilmember Mike O’Brien – as well as a local entrepreneur named Bill Gates – attend the conference in Paris, we present a limited breakdown of the stakes, and what they hope to accomplish.

How is this conference both overrated and important?

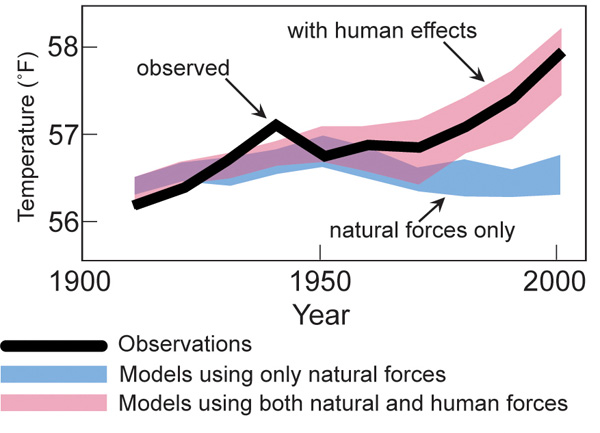

Scientists have long agreed that human activity (namely carbon emissions) is raising the temperature of the world, which will have dire consequences. Sea levels will rise, vast expanses of land will be turned into sun-parched wasteland, and more. Further, many climate scientists and environmentalists argue we’re at a crucial fork in the road. A continued lack of serious action to reduce carbon emissions, they contend, will lead to irreversible consequences for the world.

Past global agreements like the Kyoto Protocol of 1997 tried to tackle this problem head on. That didn’t work out well. The U.S. refused to ratify the agreement, and fellow major emitters like China and India refused the proposed cuts.

Some have compared this conference to that moment. But because Kyoto's “top-down” approach failed, this latest attempt is much more modest, and directed by what countries have deemed realistic.

Ahead of the conference, the U.S. has vowed to cut emissions by more than a quarter below 2005 levels by 2025. China, more modestly, has vowed that it will reach peak emissions by 2030, after which it will begin to reduce. Brazil will reduce emissions, and increase enforcement against illegal clear-cutting in the Amazon. The list of pledges goes on, and can be found here.

If that doesn’t sound like drastic action in the face of a serious problem, it isn’t. Every major emitter in the world has made an emissions-related pledge, but observers say they'll be woefully inadequate for preventing crises in coming decades. Under the current pledges, the world will heat up by 3 degrees Celsius by the end of the century, a minor-sounding landmark that will have serious repercussions. To climatologists like former NASA scientist James Hansen, carbon dioxide levels in the world's atmosphere are already at unacceptable levels.

Is there a reason not to be skeptical?

This conference has brought every major carbon emitter in the world to the table, and obligated them to produce a plan that acknowledges the climate problem and sketches out some commitments. If any progress is to occur on this issue, it has to include efforts from every major emitter. Solving the problem will require decades of coordinated international commitment, and every journey must start with a single step.

For the conference to be called a success, however, it must produce an agreement that holds countries to the commitments they’ve made, and provides a structure to build on them. That means a regular schedule to review the pledges and make them better. This means transparency about how countries are proceeding. Should a robust structure on these issues not be solidified, the value of this year’s effort will be questionable beyond political optics.

Further, Bill Gates has used the conference as impetus to create a major new investment in the development of clean energy technology. Given the modest ambitions of most major nations in their climate pledges, a stronger push in this area is important.

Why are Governor Jay Inslee and council members from Seattle and King County there?

Due the complicated interplay of national economies and governments, the U.S., European Union, and other major participants in the conference are being fairly conservative in their climate pledges. States and cities are smaller and nimbler, however, and can spearhead more aggressive approaches.

“Cities have to be a leader,” says Seattle City Councilmember O’Brien. “Cities like Seattle have been one of the national and global leaders on climate. I think it’s important for Seattle to have a presence.”

While he will not be a part of the conference’s most crucial meetings and discussions, O’Brien says he’ll be in Paris networking with peer cities around the world, sharing plans and best practices. County Councilmember Phillips, Gov. Inslee, and about two dozen other individuals will also be representing the state, which is a signatory to a more ambitious effort being organized around the conference named Under 2 MOU.

This effort is being led by California Gov. Jerry Brown, and features dozens of “subnational” signatories among the world's larger cities, states and regions. The goal is to be bolder than nations, forging partnerships and commitments between smaller partners – Washington is “prepared to partner” on a clean fuels program with other West Coast states, for example.

“This is a global challenge,” says O’Brien. “It’s not if Seattle does [more than] Portland, then yay we win….We need to be moving swiftly, but thinking long term….There are so many political interests invested in not changing the status quo. We need to balance enough hope and inspiration and ground it in reality so we’re actually doing the work.”

How can all of this go wrong?

Where the U.S. Republican Party once helped lead the environmental stewardship movement, many members of the modern party are vehemently opposed to any efforts in that department, beyond those with the blessing of big industry players.

The key vulnerability for any agreement reached likely involves subsidies for developing countries. Countries like the U.S. have benefitted from environmentally harmful practices in the past. Developing countries argue, from that starting point, that they should be compensated for refraining from these advantages as they build themselves up. Many countries have demanded huge subsidies to make up for all the revenue they’d lose while curbing carbon emissions. India, for example, is currently demanding $160 billion per year.

President Obama has pledged $3 billion over four years to a fund helping these countries, but that will demand approval from Congress. In current form, that seems unlikely.

Further reading:

The Guardian, with a compelling feature on the conference's stakes and history.

New York Times, with explanations of the stakes stakes and regular updates

Vice News, with coverage of environmental activism around the conference, and security in Paris following November's terrorist attacks

BBC, with regular dispatches and commentary from the conference

--

Crosscut's David Kroman contributed to this article.