The Legislature had for years claimed it was exempt from the 1972 voter-approved Public Records Act, meaning legislators could keep secret memos, calendars, emails and other documents. The state Supreme Court in 2019 ruled otherwise.

As lawmakers try to figure out how to disclose records that other government agencies provide, it fell to Senate Majority Leader Andy Billig, a Democrat from Spokane, to try and get a handle on the situation. Copies of electronic chats among 28 Senate Democrats from last year were released on Friday to Crosscut. They are some of the roughly 1,000 pages of documents released in response to a public-records request aimed at uncovering what lawmakers are talking about in private while doing the public’s business. Those documents included hundreds of pages that were initially redacted under a newfound exemption that lawmakers are claiming they have: “legislative privilege.”

A review of the electronic chats show they include everything from policy discussions between Democratic lawmakers to gossipy remarks about their peers. There is even a suggestion by two Democratic lawmakers – which was never redacted – that Democratic Lt. Gov. Denny Heck may have intentionally ignored a Republican, Sen. Simon Sefzik of Ferndale. Sefzik, who is in his early 20s and was the Legislature's youngest lawmaker, was apparently seeking to speak during a debate while Heck presided as president of the Senate.

In an interview in his office at the Capitol Monday, Billig said he went through the electronic chats and applied “legislative privilege” to the messages of other lawmakers.

“As the majority leader, I'll look at what's eligible for legislative privilege or attorney/client privilege, and make that call," said Billig. Asked whether he had redacted the documents of other legislators, he said: “I did, initially.”

Billig’s account confirms that legislative leaders have claimed a constitutional right to shield the records of other state lawmakers. It’s the latest morsel of information to emerge about how the Legislature conceived and is practicing its new doctrine of concealment.

The Senate has since tweaked that policy on letting legislators cover up other lawmakers’ records. The change came after the Senate received a public-records request from Crosscut on documents relating to legislative privilege, Billig said. Lawmakers must now assert their own individual constitutional right to conceal their own documents, he added. It remains to be seen who – if anyone – is legally liable for decisions about redacting lawmakers’ records.

“I actually think it was your request that forced us," said Billig, adding: "Not forced us, I think it was your request that caused us to reevaluate."

"I felt that, on reconsideration, every member should look at this individually," Billig continued. "Even if it means that essentially one member is going to in effect be waiving [their legislative privilege] for another member. And so while less efficient, it's more transparent.”

Letting the courts decide

The state Public Records Act requires lawmakers to disclose emails, memos, texts and other messages. In 2017, 10 news organizations challenged lawmakers’ contention that the law didn’t apply to them. Two years later, the Washington Supreme Court affirmed that lawmakers must indeed disclose their records, just like most other local and state government officials.

The Tacoma News Tribune and the Olympian first reported the use of “legislative privilege” last month.

The concept quickly drew a legal challenge. Billig and House Speaker Laurie Jinkins, D-Tacoma, have said it will be up to the courts to decide if they are breaking the law or if "legislative privilege" passes constitutional muster.

Until then, a host of questions remain about this new practice. At least two legislators have said they never requested that their records be withheld; someone else made that choice for them. Republican legislative leaders in the minority have expressed uncertainty about how Democratic leaders and the attorneys in the House and Senate are using the practice.

Citing the lawsuit against the Legislature, Billig said he couldn’t discuss specifics about when lawmakers are purportedly allowed to withhold records under “legislative privilege.”

“Because there’s a lawsuit, I don’t want to talk about what the justification of legislative privilege is,” said Billig.

Advocates for government transparency – who contend that the Legislature is breaking the law – remain skeptical of “legislative privilege.” George Erb, secretary of the Washington Coalition for Open Government, described the practice as: “a bit of shifting sands.”

“This legislative privilege, the way it's been explained, it seems fuzzy around the edges,” Erb said.

The Washington Coalition for Open Government has requested a host of records related to the process, including digital information that may reveal who precisely is redacting documents on behalf of lawmakers.

Lifting their privilege

Last month, Crosscut requested copies of all Senate records in 2022 in which legislators had redacted documents citing “legislative privilege.”

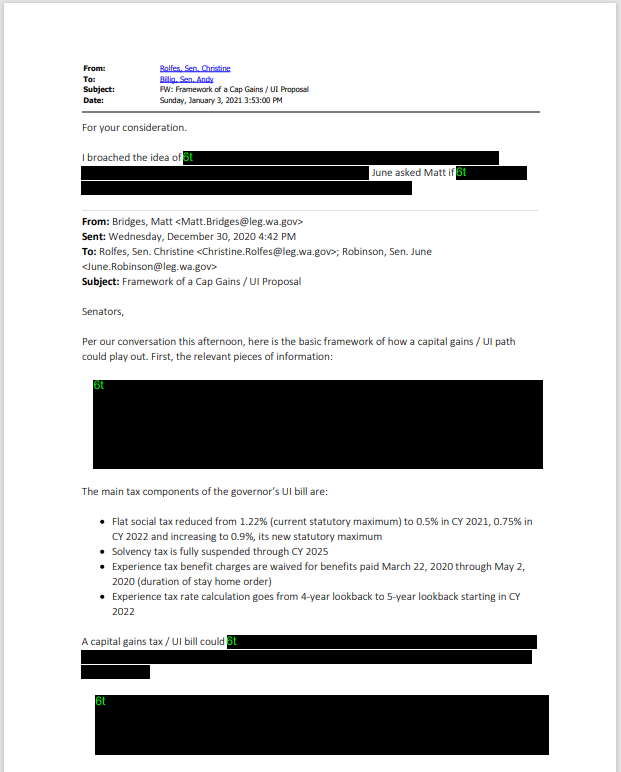

The redacted documents released to Crosscut Friday include blacked-out emails and memos related to the capital gains tax.

Those redacted messages include emails by Billig; Sen. June Robinson, D-Everett, sponsor of the bill that created the tax; and Sen. Christine Rolfes, D-Bainbridge Island, chief Democratic budget writer in the Senate. Rolfes and Robinson didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Senate records officials also released what appear to be the same batch of documents, but this batch is completely unredacted. The unredacted records were made possible because an unspecified number of legislators lifted their constitutional right to keep them secret, according to Washington Senate Public Records Officer Randi Stratton.

Stratton did not respond to a request from Crosscut seeking the list of lawmakers who waived their “legislative privilege” to allow the documents to be revealed.

Last month, the Washington state Supreme Court heard oral arguments on the capital gains tax – passed two years ago as Senate Bill 5096 – in a case known as Quinn v. Washington.

Documents related to that bill appear to have been redacted in response to a public-records request by Jason Mercier of the Washington Policy Center.

In an email, Mercier said he received the redacted copy of one document – an email between Rolfes and Billig – in an installment of records that was provided to him last November. That document spelled out a potential framework for the proposed capital gains tax, according to the unredacted copy provided to Crosscut.

And then, on Jan. 20, Mercier said he received the unredacted copy of that document – without explanation – in a later installment of records for his request. That release came just days before the state Supreme Court heard oral arguments on the capital gains tax’s legal challenge.

“There was no communication about a change in status, the unredacted record just was included in the last installment,” wrote Mercier.

In his interview, Billig said that he didn’t think the withheld documents on the capital gains tax would have any bearing on the case before the Supreme Court.

“I don’t think so, but I have no idea,” he said. “I can’t imagine.”

In an email Monday, Brionna Aho, spokesperson for the state Attorney General’s Office, said the shielding of Democratic lawmaker records related to the capital gains tax won’t have a bearing on the court case.

"If the plaintiffs in the capital gains litigation thought that any documents could possibly impact their case, they could have requested those documents through the discovery process (like any party in any lawsuit)," wrote Aho, whose agency is tasked with defending the Legislature before the court.

"But the plaintiffs in these two consolidated cases made no requests for documents whatsoever and instead argued that the tax was unconstitutional across the board as a matter of law,” she added. “Because they never requested anything through discovery, they could not argue now that the court should consider documents they never sought."

Former Washington state Attorney General Rob McKenna, who is one of the attorneys representing the plaintiffs who contend that the capital gains tax is unconstitutional, didn’t respond Monday to an email seeking comment.

Whose privilege?

An inspection of the 800-page batch of records released to Crosscut raises other questions.

Many of the records feature the name of a single lawmaker at the bottom of the page, which may or may not be the legislator who claimed legislative privilege.

Stratton, the public records officer, didn’t respond Monday to an inquiry asking if the last names of lawmakers that appear at the bottom of the released documents correspond to the legislator who exerted a constitutional right to shield them.

One redacted document is labeled “Pedersen” at the bottom.

But in an email to Crosscut last month – and in an email again Monday – Senate Democratic Floor Leader Jamie Pedersen of Seattle said he never claimed legislative privilege to withhold documents. He supplied to Crosscut a copy of an email he sent Senate staffers last year approving the release of that document, which also concerned the proposed capital gains tax.

In his email Monday, Pedersen wrote that the scenario “illustrates an important point about how I think that the Senate and House have (had?) been handling this issue.”

“When multiple legislators are involved in a single exchange, the information has been released only if ALL waive the privilege,” Pedersen wrote.

Last month, Pedersen wrote “I do not have any visibility into the interactions among Senate counsel, Senate administration, and the public records office about whether or when records are redacted.”

Elsewhere in the batch of records, an identical copy of the document Pedersen was named on was also redacted. The bottom of that page features the last name of state Sen. Karen Keiser, D-Des Moines.

But, "I do not recall ever asserting legislative privilege regarding any communications about the capital gains tax," Keiser wrote in an email.

Sen. Javier Valdez, D-Seattle, told Crosscut last month that he had never asserted a constitutional right to shield documents from the public. On Monday, Sen. Jesse Salomon, D-Shoreline, and Sen. Joe Nguyen, D-White Center, wrote that they too have never exerted legislative privilege to shield records.

The records released Friday also acknowledge that Senate officials had “erroneously withheld” 145 pages of memos and emails and an Excel spreadsheet dealing with the once-a-decade redistricting process to redraw political boundaries for the state Legislature.

That effort became infamous after the appointed commission confessed that it broke state law in 2021 by conducting secret negotiations.

The five-member commission, which gathers once a decade after the U.S. census in order to redraw political districts, agreed to a settlement to resolve a pair of open-meetings lawsuits filed against it.

“In the second production, you will note that there are 145 documents and an excel spreadsheet that were erroneously withheld in their entirety under a claim of legislative privilege in a previous production,” according to a letter by Stratton accompanying the release of the records. “The error has since been corrected with the original requester who has received the unredacted documents.”

Those records were originally requested by Jamie Nixon, who was a staffer during the Washington State Redistricting Commission. The existence of those documents, which was first reported by the Tacoma News Tribune and the Olympian, meant unredacted versions were provided about three months after the redacted versions.

Billig said that withholding those records didn’t violate the law, because the records request is still open, meaning that future installments could still be provided. He explained the redaction as a miscommunication, and said he had made clear to staff that he didn’t want to exert legislative privilege on documents related to redistricting.

"No, it is not a violation of the law for documents to be withheld for a lawful reason," Billig wrote in an email. "The fact that Legislative privilege was originally used and then the unredacted documents were later released, even though legislative privilege could still be claimed, is well within the law."

The Washington Public Disclosure Commission is a small agency that oversees some enforcement of the suite of ethics-in-government laws passed by Washington state voters in 1972 as part of Initiative 276. That initiative created the PDC and allows it to oversee the regulation of campaign-finance laws.

But the agency doesn’t oversee any part of the Public Records Act, according to spokesperson Kim Bradford.

Bradford referred questions about the Public Records Act to the state Attorney General’s Office.

Aho, the Attorney General's Office spokesperson, confirmed that the agency hasn't yet received any complaints or self-reports related to any legislative violations of the Public Records Act.

Correction: a previous version of this article described Simon Sefzik, who lost election in November, as a current member of the Legislature.