The mayor of the 7,500-person town on Washington's Olympic Peninsula recently promoted QAnon during a public radio interview, telling listeners to go watch a well-known QAnon conspiracy video. A recording of that interview was posted on Sequim’s official website and boosted by the city’s Twitter account.

But the baseless far-right conspiracy theory isn’t being promoted just by mayors of small communities in a remote corner of the United States. At least two Republican candidates for the Washington Legislature have knowingly spread QAnon content online, while in Oregon, a Republican candidate for the U.S. Senate, Jo Rae Perkins, is an avowed QAnon supporter.

Another Washington legislator who posted a link to a QAnon conspiracy site said she did so without realizing it — then made national news by cursing out a reporter who wrote a story about it.

While QAnon has morphed to encompass many different conspiracy theories, its followers claim to believe that President Donald Trump is fighting a “deep state" network of child-sex traffickers embedded in the U.S. government and the media, a "cabal" that includes prominent Democrats and celebrities. At times, QAnon supporters have also promoted the idea that Democrats are sacrificing babies and eating them or drinking their blood — one of a cornucopia of falsehoods, some of which echo decades-old anti-Semitic propaganda.

Joseph Uscinski, an associate professor of political science at the University of Miami, said QAnon is best described as “a decentralized online conspiracy cult,” rather than a conspiracy theory, given the “radical” nature of QAnon followers’ beliefs.

The sprawling pro-Trump conspiracy theory began on the far-right online message boards 4chan and 8chan, which are known hotspots for racist and white supremacist views.

At the center of QAnon is an anonymous online figure known as “Q,” who claims to be a U.S. government insider. Since 2017, “Q” has regularly posted “Q drops” online, which Q followers then try to decipher.

Nationwide, 24 congressional candidates appearing on the November ballot have either endorsed parts of the QAnon conspiracy theory, given the theory credence or otherwise promoted QAnon content, according to Media Matters, a liberal nonprofit that monitors conservative media. All of those candidates are Republicans, except for three who identify as independents, Media Matters says.

Trump hasn’t embraced the QAnon conspiracy theory outright. But he has encouraged it, including by sharing social media posts from QAnon-linked accounts and saying last month of QAnon supporters, “I’ve heard these are people that love our country.”

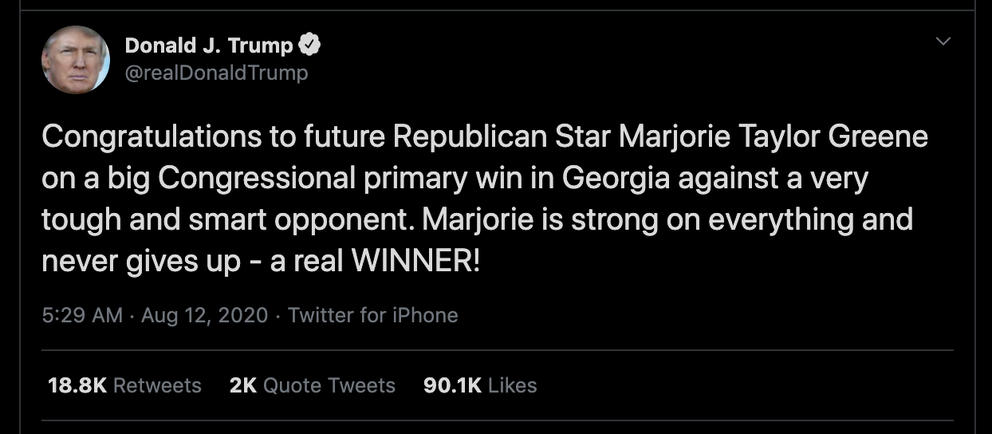

Last month, Trump also spoke favorably about Marjorie Taylor Greene, a Georgia congressional candidate who has espoused QAnon theories. Trump called Greene a “future Republican star.”

Uscinski said public opinion polls show QAnon remains a theory on the political fringe, despite the increased media attention it has received this year. Far more people tell pollsters they believe other conspiracy theories, including that there was a coverup surrounding the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, or that the U.S. government is hiding the truth about 9/11, said Uscinski, who studies and writes about conspiracy theories in politics.

At the same time, if politicians believe in QAnon and are using their public platforms to try to promote and spread the conspiracy theory, “that is a serious problem and one that needs to be exposed,” Uscinski said.

He said the Sequim mayor’s comments on QAnon seemed to fall into that category, as did statements by Perkins, the Republican U.S. Senate candidate from Oregon.

“We should not have political leaders who are believing in nonsense, because they can act on that nonsense.” Uscinski said. “What concerns me is that you have people latching on to an anonymous, unaccountable leader. I’m concerned that this person could encourage bad behavior among followers.”

Connections to violence

Kathryn Olmsted, a professor of history at the University of California, Davis, said she views QAnon as being much more dangerous than conspiracy theories that center on historical events, such as JFK’s assasination or the Sept. 11 attacks, because QAnon focuses on events unfolding in real time.

“They’re saying there is this group of satanic pedophiles who are ruling the country and hurting children,” said Olmsted, who wrote a book on anti-government conspiracy theories. “If someone really believes that, they would be motivated to violence, because, well, we’ve got to stop these satanic pedophiles.”

Last year, an FBI memo obtained by Yahoo! News identified QAnon as one of several fringe conspiracy theories that could spur people to commit acts of domestic terrorism. The FBI memo cited an incident in which a QAnon supporter parked an armored car on the bridge next to the Hoover Dam in 2018, as well as a case where an Arizona man led a group of armed veterans to search homeless camps for evidence of sex trafficking. The Arizona man, who was later arrested, cited QAnon conspiracy theories while accusing law enforcement of a cover-up.

Previously, a similar unfounded conspiracy theory known as Pizzagate, which falsely alleged that Democrats were trafficking children in the basement of a Washington, D.C., pizza restaurant, prompted a man to fire an AR-15 rifle into the restaurant in 2016.

More recently, West Point’s Combating Terrorism Center, an academic institute within the United States Military Academy, released a report citing several violent incidents related to QAnon.

Given those things, Olmsted said it’s concerning to see the president and other political figures giving the QAnon movement “a wink and a nod,” something she described as something new and unprecedented.

Matthew Randazzo V, a past chair of the local Democratic Party in Clallam County, where Sequim is located, said the open discussion of QAnon among government officials proves that far-right extremism is on the rise.

“You are seeing it mainstreamed in a way you have never seen before, and I think it is largely due to an extreme paranoid backlash to the Black Lives Matter protests and a resentment toward the shutting down of the economy due to COVID,” said Randazzo, an author and former state official who now advises Native American tribes on public policy issues.

Recently, Randazzo has been active in pointing out far-right conspiracy theories on Twitter, including by drawing attention to the mayor of Sequim’s comments.

In a prepared statement posted on the city’s website last week, Armacost said he shouldn’t have discussed his personal views about QAnon during last month’s radio interview, which was part of a city-sponsored question-and-answer session called “Coffee With the Mayor.” He declined to answer more questions when reached by phone.

In a similar vein, Sequim City Manager Charlie Bush said the mayor’s comments “do not reflect policy positions of the Sequim City Council or the organization.”

President Donald Trump and Vice President Mike Pence stand on stage during the first day of the 2020 Republican National Convention in Charlotte, N.C., Aug. 24, 2020. Trump has refused to criticize QAnon when asked about the baseless conspiracy, while Pence recently canceled a planned appearance at a fundraiser hosted by QAnon supporters. (Andrew Harnik/AP)

QAnon on the campaign trail

Other politicians in Washington state also are actively talking about QAnon.

In Eastern Washington, Rob Chase, a Republican candidate for the state House, has shared QAnon content on social media, as well as in posts he has written for a conservative website called the Inland NW Report. Chase is running to replace state Rep. Matt Shea, R-Spokane Valley, who chose not to run for reelection this year after an investigation found Shea took part in domestic terrorism.

Chase’s QAnon comments were reported on at length last month by The Inlander, a Spokane-based alternative weekly.

In a response, Chase wrote a new post linking again to QAnon content, while criticizing the Inlander article as an attack on his right to freely discuss ideas.

“So what is wrong with asking a question?” Chase wrote.

In this case, plenty, said Uscinski, the University of Miami political science professor.

“It’s like, ‘I don’t believe that satanic pedophiles are eating babies for magical powers — I’m just asking questions,’ ” Uscinski said. “‘Are baby eaters controlling our government? I’m just asking questions.’ ”

“There are reasonable questions to ask, and there are unreasonable ones,” Uscinski said. He said people who believe conspiracy theories will often “sort of mask their beliefs” under the guise of asking questions or researching.

In the Puget Sound region, Amber Krabach, a Republican state House candidate from Woodinville, has regularly posted QAnon-related memes and tweets, sometimes under a hashtag that abbreviates the QAnon rallying cry, “Where We Go One, We Go All.” Krabach is running against state Rep. Larry Springer, D-Kirkland, in the 45th Legislative District.

In a phone interview Tuesday, Krabach said she doesn’t believe many of the extreme theories promoted by QAnon followers, including the ones about Democratic satanists and child-eating pedophiles running the government.

She said she considers Q’s posts just a starting point for her to do her own research, “kind of like clues in a puzzle.”

Yet Krabach has also posted on Twitter about “the Great Awakening,” which often has a darker meaning. According to the authors of the West Point report, that term is one QAnon supporters use for “the reckoning Trump is thought to bring to what they see as the ‘Cabal’ that has infiltrated the U.S. government.”

Krabach said she interprets “the Great Awakening” differently, as people waking up to the realities of child-sex trafficking. She said she used a similar hashtag, “#NothingCanStopWhatIsComing,” to refer to Trump’s reelection, not to impending mass arrests of Trump’s political opponents or a military coup of the U.S. government.

Then there’s the case of state Rep. Jenny Graham, R-Spokane, who recently shared links to online conspiracy theory sites, one of which promoted theories tied to QAnon.

Graham told Inlander reporter Daniel Walters last month that she hadn’t been aware of the QAnon conspiracy theory at the time she shared those links.

This week, Graham made national headlines after leaving Walters a profanity-laden voicemail lambasting his coverage. Graham didn’t respond to an email from Crosscut seeking comment for this article.

State Rep. J.T. Wilcox, the Republican leader in the Washington state House of Representatives, said Graham takes issues of sex-trafficking very personally because of her family’s history. Graham’s sister, Debra “Debbie” Estes, ran away from home and was later murdered at 15 by Green River Killer Gary Ridgway. Graham told Crosscut earlier this year that Estes was forced to perform sex work as a means of survival before she was murdered.

“She wishes she wouldn’t have used that language,” Wilcox said of Graham, whom he spoke to about the incident earlier this week.

More broadly, Wilcox said QAnon is not something Republican legislators or most GOP candidates are embracing. He called some of the central tenets of the QAnon conspiracy theory, including that Democrats and celebrities are satanist child-traffickers, “not true at all.”

Wilcox said he is disturbed by the spread of misinformation he is seeing online recently, including people posting ideas lifted from the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a hateful propaganda pamphlet that formed the basis of Nazi ideology in the 20th century. Some experts have said QAnon is a rebranded version of that debunked anti-Semitic conspiracy theory.

Neither Chase nor Krabach is a candidate that the House Republican Organizational Committee, the House Republicans' campaign arm, recruited to run for office this year, Wilcox said.

Even so, Chase is likely to win election to the seat being vacated by Shea in the 4th Legislative District, Wilcox said.

Wilcox said he has never spoken to Chase — but if he wins election to the state House, he will receive the customary warnings new members receive about the danger of spreading false information online.