Tjoelker was one of the many to show up May 9 to tiny Lynden in Whatcom County for the “Lynden Freedom Parade,” which followed the Dutch-style tradition of parading through town in vehicles instead of walking, although many showed up on foot to hold signs of solidarity from the side.

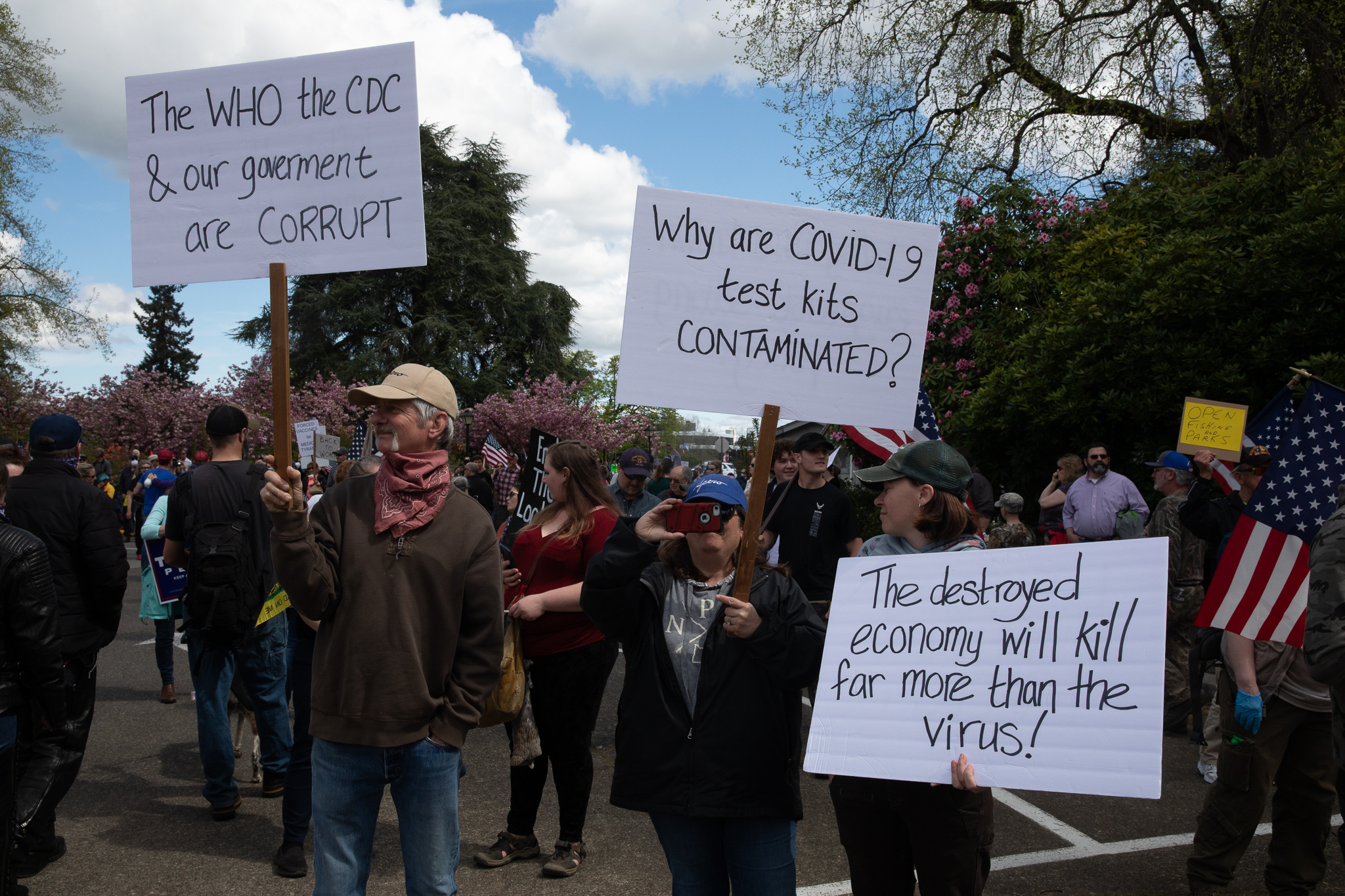

The protest in Lynden against Gov. Jay Inslee’s stay-at-home orders in the wake of COVID-19 and in favor of reopening the economy was one of many across the state and the country to demand economic freedom and fewer government restrictions on people’s activities.

Julie Beld Anderson, a 51-year-old local business owner in Lynden, organized the parade for her town, which, according to her count, drew more than 1,200 people and 500 vehicles. In part, they were advocating for their smaller county to be treated differently than King and Snohomish counties, where most of the coronavirus cases have been identified.

Anderson sees the shutdown as political, but doesn’t want it to be that way. She doesn’t know why it’s become so divisive in Washington, but feels at times that liberals are trying to “ruin the economy so that no one will vote for President Trump in the next election.”

But she still wonders: Would they really do that?

How should we reopen? Here's what one model could look like.

Cornell Clayton, director of the Foley Institute for Public Policy and Public Service at Washington State University, said he’s seen a deepening of political polarization as the coronavirus crisis has surged forward. That’s in part because of the White House strategy to attack Democratic governors, he said, but it also follows a general shift in American society in which every major issue turns partisan.

Clayton doesn’t think Donald Trump is the cause of such deep polarization, but rather a symptom of it after building up for decades in the country. And public attitudes on political issues are largely driven by cues from party figures, he said.

“If President Trump comes out and says, ‘These governors are stomping on your freedom and they’re too restrictive, and this is all about politics trying to bring my administration down’ — eventually that will shape the attitudes of Republican voters,” Clayton said.

“If Democratic governors and leaders are saying this is a real crisis, we need to keep things closed and contained, that we should think this is a health crisis, not an economic problem initially, then that will shape Democratic voters’ views as well,” he added.

It’s similar to another public health and science issue: global warming. It’s not that Republicans don’t believe in science or don’t understand science, Clayton said, but it’s the rhetoric from their affiliated parties that help form their opinions.

Media has also played a huge part in COVID-19 partisanship, Clayton said. If you consume Fox News, it echoes the White House’s message, he said: If you watch CNN or MSNBC, you’re getting a very different message.

This divide was clear in a recent Crosscut/Elway Poll focused on the coronavirus. Most of those who watched Fox News said they thought Trump was doing a good job handling the crisis; viewers of CNN or MSNBC were not satisfied with the White House’s actions.

“So that framework, that media framework, makes the ability of party elites to shape public attitudes even stronger,” Clayton said.

Anderson, the Lynden parade organizer, is a Republican and said she easily gets glued to the news during these times. She used to watch multiple channels, but after watching CNN and MSNBC “twist” Trump’s words, she said she couldn’t watch it anymore: “It was maddening.” So she sticks with Fox News.

Various voices across the state have joined Anderson’s call to open Washington: rallies at the state Capitol building in Olympia, letters from state legislators and proclamations from small-town mayors.

But these protesters are at odds with the majority of Washington state. The Crosscut/Elway Poll, conducted in April, found that 76% agreed that the government’s restrictions were working to control the spread of the virus, and 61% thought lifting restrictions too soon risked public health.

Gov. Inslee warned that if his loosening of restrictions as part of his four phase plan led to an increase in infection rates and hospitalizations, he "would not hesitate to scale these efforts back down."

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and many other public health experts have warned that America is not out of the woods yet. On May 12, when U.S. Sen. Patty Murray, D-Washington, expressed concerns about opening up the economy too soon and the mixed messages from Trump, Fauci said if federal guidelines aren’t followed, small spikes could turn into larger outbreaks and that the "consequences could be serious."

Anderson isn’t convinced about those consequences affecting Whatcom County. She said the large number of people over 60 at her parade didn’t concern her. She is sick of what she sees as the government holding her hand. Her son has medical issues, with reduced lung capacity that could make him more susceptible to serious complications from COVID-19. She said they know how to keep him safe; they’ve done it for years already.

“I’m tired of this, I can protect myself. … We don’t need somebody to tell us how to do it and what to do,” Anderson said. “I think the elderly are responsible for themselves and the immunocompromised, or people with underlying conditions.”

At the time Anderson shared her story, there had been 32 deaths in Whatcom County, of which 75% were in long-term care facilities. Of the eight who died outside of facilities, she doesn’t think those numbers justify closing the entire economy.

“That's where our whole economy is shut down for those eight people, right now,” Anderson said.

In the beginning of the stay-at-home order, she agreed with the measures. Now, she thinks it’s safe to open their county back up, or at least Lynden, which has a population of about 15,000.

“We went out and we put our hearts into this and did it right. So not only did we flatten the curve, but it dropped off a cliff,” Anderson said. “Now it’s all about Gov. Inslee want[ing] zero cases — does he really want zero cases in the whole state?… Does it seem feasible to you, out of over 7½ million people?”

She did take her at-risk son out to the parade, she said, after he had been inside for almost two months. The theme of the parade, after all, was to “save lives and save businesses,” she said. “We can do both. … Yes, he’s at risk — at the same time, you know, we feel like it’s perfectly fine to be out like at the parade.”

She said she’s been following the numbers in Whatcom County closely, and the 7% of people tested positive don’t warrant enough for her to be concerned.

Anderson said the number of deaths per total population in the county was infinitesimal, saying it was 0.000002%. The actual rate is 0.015%.

As of May 13, Whatcom County had 343 confirmed cases and 35 deaths in a population of just over 229,000 people. That’s a 10.2% fatality rate among those with COVID-19, double the state’s average of 5.5%. Of everyone the county tested — just 2% of the population so far — 7.7% were confirmed positive. Again, that’s higher than the state's 6.6%.

But Anderson did point out that the majority of the fatalities occurred among the elderly and were mostly in skilled nursing facilities. In her county so far, 100% of the deaths were indeed among people 60 years and older, although there are confirmed cases in every age bracket.

Even looking at numbers has become polarized. Projections of death tolls and confirmed cases have varied as the health crisis has grown, enabling politicians and leaders to choose the estimate most favorable to their own opinions.

“Projections of the death toll produced by the current economic shutdown are often politically motivated, but the effects on human life are real,” Dr. Marty Makary, a surgeon and professor of health policy at the John Hopkins School of Public Health, wrote in a New York Times opinion piece.

Wearing masks has also become political. The Washington Post surveyed Americans in mid-April and found that 73% of Democrats have worn a face covering in public, compared with 59% of Republicans and 58% of independents.

That could be a result of confusion surrounding federal and state advice on the issue. Back in early March, Fauci, the nation’s leader on infectious diseases, said there was no reason for the average person to wear a mask, and World Health Organization guidance says only that people caring for a sick person needed to wear a mask. But new studies have prompted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to change course, and Fauci now recommends wearing a face covering in social settings, all while emphasizing this does not replace hand washing and social distancing.

It’s not just party lines that divide us, WSU’s Clayton said, it’s “all sorts of other dimensions,” including geographic, gender, religious and cultural lines. The urban-rural divide in Washington is especially pronounced, especially with rural counties being overwhelmingly Republican, he said.

“Also in rural areas to date, they have not been so hard hit by the health consequences of COVID. So it's seen primarily as an urban problem,” Clayton said. “Now, I think that changes as soon as some of these smaller towns — and that's happening now in the heartland, and also happening in Yakima — as they start to see the real life consequences.”

While living in an area with a low number of deaths and confirmed cases may make opening up the economy seem appealing, health experts warn about the ability of rural places and small towns to handle an influx COVID patients. The population in those areas tends to be older, sicker and have less access to medical care.

Currently, four of the 10 counties with the highest death rates in the country are rural. In Washington, as of May 15, rural Yakima County leads the state with the highest per capita rates of COVID-19. It has the third highest number of total cases, as well as deaths, although it is only the state's eighth most populous county.

Neighboring counties Franklin and Benton are second and fourth in per capita cases, although they are, respectively, only the 14th and 10th most populated counties in Washington.

Robert Dewayne, Jr., a 66-year-old retired medical center software analyst and former emergency medical technician in Walla Walla, doesn’t see why people are treating the novel coronavirus differently from SARS and swine flu, two outbreaks he experienced as an EMT.

While Dewayne acknowledges he “isn’t a doctor,” his background in both analyzing data and medical knowledge has helped inform his decisions.

“The whole thing is ridiculous,” Dewayne said. “Nothing they’ve come forward with yet has proven to me that this is any other than a slightly different strain.”

The comparison has been made before: How is this different from other pandemics? SARS and MERS were both very deadly, but not as easily transmitted. H1N1, or swine flu, was very infectious but not as deadly, with an estimate of 0.1% fatality on the high end.

While the fatality rates of SARS and MERS were extremely high, at 9.6% and a whopping 34%, SARS killed only about 774 people and MERS only 866 globally.

Rural Walla Walla County, with a population of only 60,000, has seen only two deaths and 105 confirmed cases of COVID-19, with a county testing rate of about 6%.

While WHO says influenza can spread faster than the coronavirus, and with very similar symptoms, the differences can be found in severe and fatal cases. The number of critical COVID-19 infections are much higher, and mortality rates are, so far, at 3% to 4% versus seasonal influenza’s rate, which is below 0.1%.

And even though both Dewayne and his wife have health issues that put them both more at risk, he thinks there never should have been any restrictions from the beginning. If someone is at risk, or lives with someone who is, the impetus is on them to stay safe. He doesn’t wear a mask — “you’re trapping all your own bacteria on everything and not letting it get out” — but he washes his hands regularly and knows the basics of disease prevention from being an EMT, he said.

He thinks the coronavirus will probably leave during summer and return in the fall: “If we don’t build up some immunities as a civilization, it’s still gonna wipe us out.” So he wants the economy to open, now.

And he also thinks the reluctance of Inslee to listen to the protesters is political. Dewayne is an independent, and critiques both sides of the party lines, but in the end, disagrees with Inslee and thinks liberal King County is completely at odds with Eastern Washington.

“My honest opinion is [west of] the 5 corridor should be its own state, all the way from California to Seattle,” Dewayne said. “It’s just night and day. Two different worlds.”