In other words, it’s redistricting time. Every 10 years, U.S. states redraw their maps for legislative and congressional seats using the most recent census data. Last time around, the Republican Party brazenly and effectively used this process to manipulate district boundaries in its favor, enabling Republicans in many states to win seats disproportionate to their actual support among the electorate.

Will that happen again? Here in Washington state, we can help make sure it doesn’t.

How Washington redistricting works

In many states, redistricting is nakedly political because it’s done through the normal legislative process. That gives a ruling party wide scope to protect its incumbents, mess with its opponents and redraw the lines to consolidate power. The process in our state is better, but still far from independent of the parties and their interests.

Here we have a bipartisan Redistricting Commission with four voting members appointed by the party caucuses of the state House and Senate. The commission is charged with collecting public input and drafting new maps, for which state law establishes rules and guidelines. As nearly as possible, districts should be equal in population; they should respect geographical boundaries, political subdivisions and “communities of interest”; and no gerrymandering allowed!

The four commissioners — April Sims for the House Democrats, Paul Graves for the House Republicans, Brady Walkinshaw for the Senate Democrats and Joe Fain for the Senate Republicans — released their draft legislative district maps on Sept. 21 and congressional district maps a week later. They have until Nov. 15 to hash out their differences; three of the four must ultimately agree. If they reach an impasse, the state Supreme Court steps in.

One danger of this arrangement is that it introduces the logic of negotiation. It just makes sense to come to the table with an initial proposal that privileges your party — after all, things are only going to get worse. The final results are likely to emerge more from partisan horse-trading than from impartial analysis.

“It’s a flawed system because it’s built to maintain the power of the two existing parties,” says University of Washington law professor Hugh Spitzer, who wrote about this problem in Crosscut last year. “If the state shifts more and more, for example to the Democratic Party, it allows the Republican Party to reinforce or maintain its position, even as it loses support, through the design of districts,” he says.

Spitzer thinks redistricting would be better undertaken by an independent commission or demographer. But, for now, this is the system we have. So how do the maps compare?

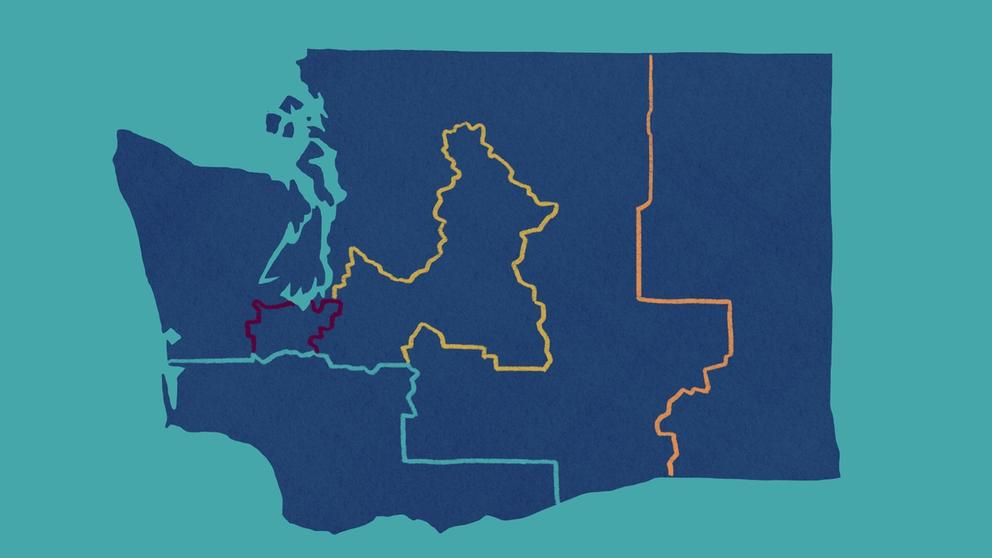

The maps

In their first attempts at mapping the new legislative districts, both parties made some predictable plays. The Republican commissioners sought to create more competitive districts, while the Democratic ones prioritized fair representation and consolidation of communities of color. An analysis produced by the Senate Democratic caucus is helpful in understanding the differences, and some important problems.

First, there’s splitting. The districting process is supposed to minimize arbitrary divisions of areas that already have some political, social or geographic unity. It’s impossible to avoid this entirely, but at least in the case of cities, the Democrats’ maps do a much better job. Sims and Walkinshaw, the Democratic commissioners, both manage to substantially decrease the number of cities split and the total number of splits; Walkinshaw’s map nearly halves the number of cities split from 39 to 20. Republican Commissioner Graves’ map is close to a wash, but Fain dramatically increases the number of cities split to 54.

Second, there’s the matter of displacing incumbent legislators from their current districts, or going out of the way (quite literally!) to prevent their displacement. On this score the partisanship is mutual, but it’s far more striking in the Republican camp. Walkinshaw’s map would displace 15 Republican incumbents and eight Democrats (a ratio of 1.9), while Sims’ would displace nine Republicans and six Democrats (a ratio of 1.5). On the other side, Fain’s map would displace 13 Democrats and 5 Republicans (a ratio of 2.6), while Graves’ would displace 22 Democrats and only two Republicans (a whopping ratio of 11.0).

Third, there’s the question of how well the probable distribution of seats between the two parties reflects the actual partisan breakdown of the state. A free online tool called Dave’s Redistricting App estimates that Washington state’s population is 57% Democratic; if seats in the legislature were proportionate, this would correspond to 28 Democratic and 21 Republican districts. The app predicts that both Democratic commissioners’ maps would result in precisely this split.

The Republican maps, by contrast, would be appropriate for a state that is less than 50% Democrat, according to the Senate Democratic caucus analysis.

Not surprisingly, the Republicans disagree with this portrayal. Evan Ridley, staff person to Graves, says Dave’s Redistricting App, which includes federal elections in its metric, probably overstates the performance of Democrats in state races. He also says that while it’s true his map creates only 23 safe Democratic districts, it would create a mere 15 safe Republican districts; the remaining 11 would be swing districts, nearly doubling the current six.

“Ultimately it would be wrong if either party got an automatic majority before any elections were held,” Ridley wrote to me in an email. “Democrats have an advantage, of course, so they should begin with a head start. But they should not begin beyond the finish line.”

As Melissa Santos reported in Crosscut last week, Democrats have pointed out that healthy electoral competition doesn’t necessarily mean competition between the two major parties. With a top-two primary system, matchups between more moderate and more progressive Democrats — or between a Democrat and a third-party socialist — can be just as heated and may better reflect political reality. If Washington state has a solid Democratic majority, it’s a strange notion of fairness to argue that we should be drawing districts with the goal of giving Republicans a shot at governing. If they want to win, maybe they should change their policies.

Equity concerns

As in many states, Washington’s electorate has been both shifting left and growing more racially and ethnically diverse. The population is now nearly 40% people of color, yet just one of our 10 congressional districts — the 9th, currently represented by Adam Smith — is majority minority, and even there people of color do not yet constitute a majority of the electorate. Only five out of 49 legislative districts are majority people of color, and only one has a majority-minority citizen voting-age population. In our winner-takes-all voting system, that’s a problem for equitable representation. To the extent that community and political interests cleave along racial lines, voters of color can find themselves essentially locked out.

A coalition called Redistricting Justice for Washington is pushing for communities of color, and especially working class communities of color, to be better represented. The coalition hopes to put the 9th Congressional District, which now ranges from Tacoma in the south to Bellevue in the north, on track to have a majority-minority voting-eligible population within the next few years. Another priority is to strengthen and create more majority-minority legislative districts around the state, from the Yakima Valley and the Tri-Cities to South King, Pierce and Snohomish counties.

To these ends, the coalition has proposed some maps of its own. While broadly speaking the Democratic proposals come closer, the coalition has criticized all four commissioners’ maps for diluting the potential electoral power of working class communities of color.

Ultimately, truly equitable solutions may go beyond drawing new lines. In a video analysis of the commissioners’ maps by Redistricting Justice for Washington, Kamau Chege, director of the Washington Community Alliance, argued for a system of proportional representation. Instead of single winner-takes-all districts, for example, we could have a smaller number of multiwinner districts and a system of ranked choice voting, making it possible for communities that don’t constitute a majority to still elect a candidate of choice. “Having multiwinner districts means it’s impossible for parties to gerrymander,” said Chege.

How this ends

But back to the system we have. What’s next in the redistricting process? Members of the public can comment on the proposed state legislative maps at a virtual meeting tonight, Tuesday, Oct. 5, starting at 7 p.m. A similar meeting will be held for the congressional maps Saturday, Oct. 9, starting at 10 a.m. Written, audio and video comments can be submitted online.

Then it’s negotiation time. What outcome should we hope for? Spitzer thinks a deadlock might actually be the best case scenario.

“If the Republicans are adamant about developing gerrymandered districts to preserve their possibility of power in the Legislature and in Congress, [the Democrats] should just dig in their heels and throw it to the Supreme Court,” he says. The court could then hire an independent expert “who would just design the districts based on the constitutional standards and without any hanky-panky.”

While the Republicans would probably be the big losers in this case, an independent expert might make decisions that certain Democrats in power don’t like either. For example, Adam Smith could be booted out of the 9th Congressional District — something Redistricting Justice for Washington’s map would accomplish, but which Sims and Walkinshaw studiously avoid.

Passing the buck isn’t usually a noble act, but in this case it may be the best outcome for democracy in Washington state. If that’s what it takes to squish the gerrymander, I’m all for it.

Correction: This opinion column has been updated to reflect that only 5 out of 49 legislative districts are majority people of color, and only one has a majority-minority citizen voting age population.