Enduring the wartime hardships

Earlier that spring, President Bush had invited Mineta and his wife, Deni, to spend time at Camp David, the presidential retreat. One night after dinner, the president asked Mineta about his imprisonment during World War II.

For three hours, Mineta, an 11-term Democratic member of Congress who had served as President Bill Clinton’s secretary of commerce, shared his experience of wartime detention and its effects on him and his family.

This story was first published by The Conversation.

On Feb. 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had issued an executive order authorizing the military to round up and remove people of Japanese descent from their homes on the West Coast. Mineta, his parents, three sisters and a brother were among the approximately 110,000 men, women and children of Japanese ancestry who were escorted by armed guards to hastily constructed government detention facilities in desolate inland locations.

Without any charges brought against them, they were held under harsh conditions for the duration of the war simply because they were the same race as the enemy.

Mineta’s parents, Kunisaku and Kane Mineta, and other first-generation immigrants from Japan were prohibited by federal law from becoming naturalized citizens. After the declaration of war, they were classified as enemy aliens, no matter their loyalty to America, their adopted country. Their U.S.-born children, like young Norm, were included in the military detention orders as “nonaliens” — the government’s term invented to avoid recognizing that they were natural-born U.S. citizens.

In the spring of 1942, before the family was rounded up by the military, Mineta’s father’s business license for his insurance agency was suspended, and the family bank accounts were confiscated. The family scrambled to dispose of their household belongings since they could take only what they could carry. Ten-year-old Norm’s great heartbreak was having to give away his dog, Skippy. And yet, when he boarded a train with his family for an unknown destination, Mineta was wearing his Cub Scout uniform to show his patriotism.

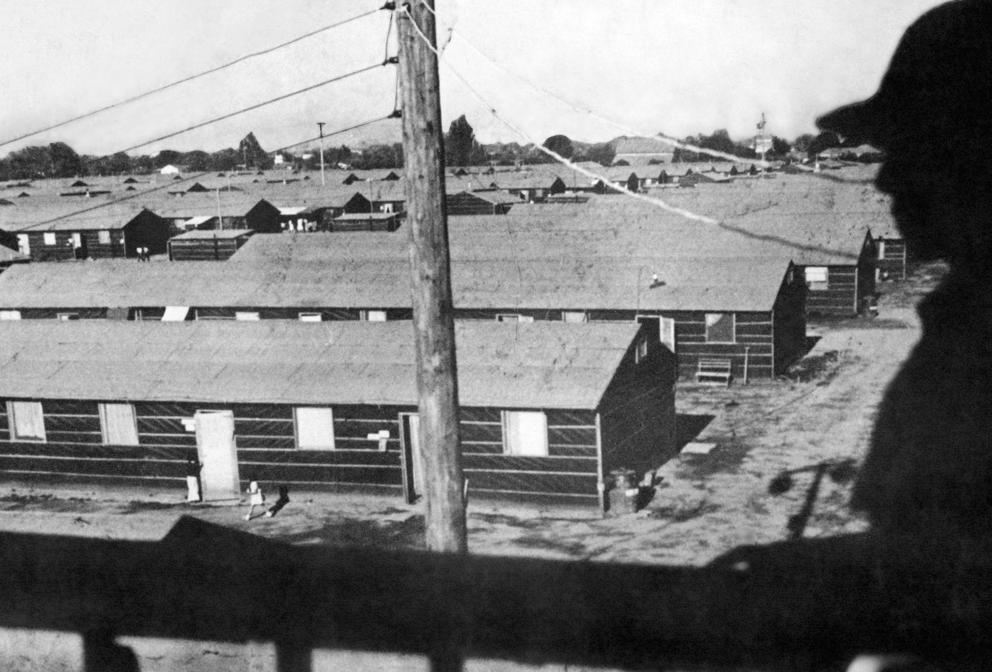

The Minetas arrived at the Santa Anita Assembly Center in Arcadia, California, in May 1942, and six months later were transferred to the Heart Mountain Relocation Center near Cody, Wyoming. During the war years, the Minetas and those incarcerated at nine other camps run by the government’s War Relocation Authority lived behind barbed wire, under searchlights, with armed soldiers in guard towers pointing guns at them.

From San Jose to Washington, D.C.

In his foreword to my book, When Can We Go Back to America?: Voices of Japanese American Incarceration During World War II,” Mineta describes how he was raised to be positive about the privilege of being an American citizen, in spite of the crushing injustice of indefinite imprisonment without cause.

When the Mineta family was able to return to San Jose, California, following the end of the war, they put the challenges of their incarceration behind them and prioritized rebuilding their lives and standing in the community. Mineta was elected student body president at San Jose High School in his senior year and graduated from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1953.

After serving three years as an Army intelligence officer in the Korean War, he joined his father’s insurance business and got involved in local politics. In 1971, he became the mayor of San Jose, the first Asian American mayor of a major American city. Then in 1974 he became the first Japanese American from outside of Hawaii to be elected to the U.S. House of Representatives.

In addition to being the first Asian American to hold a presidential cabinet position, he was one of the few individuals to serve two presidents from different political parties; in Bush’s cabinet, he was the only Democrat.

Changing the course of history

The day after the 9/11 attacks, Secretary Mineta was at the White House in a meeting with the president, Cabinet members and Democratic and Republican congressional leaders. The discussion turned to the concerns of Arab Americans, Muslims and those from Middle Eastern countries over the growing demands reported in the media that they be placed in detention facilities.

Mineta later recalled the president saying, “We want to make sure that what happened to Norm in 1942 doesn’t happen today.”

Bush later explained: “One of the important things about Norm’s experience is that sometimes we lose our soul as a nation. The notion of ‘all equal under God’ sometimes disappears. And 9/11 certainly challenged that premise. So right after 9/11, I was deeply concerned that our country would lose its way and treat people who may not worship like their neighbor as noncitizens. So, I went to a mosque. And in some ways, Norm’s example inspired me. In other words, I didn’t want our country to do to others what had happened to Norm.”

At Mineta’s direction, on Sept. 21, 2001, the Department of Transportation emailed major airlines and aviation associations cautioning against racial profiling or targeting or otherwise discriminating against passengers who appeared to be Middle Eastern, Muslim or both. The message reminded the airlines that “not only is it wrong, but it is also illegal to discriminate against people based on their race, ethnicity, or religion.” It said the department would be on the lookout to ensure that airport security measures were not unlawfully discriminatory.

Five years later, in December 2006, Bush presented Mineta with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the country’s highest civil honor, paying tribute to Mineta’s lifetime of public service. While the government of the 32nd U.S. president would not acknowledge Mineta as a citizen, the 43rd president called him a patriot and “an example of leadership, devotion to duty and personal character” to his fellow citizens.

In 2019, Mineta reflected on how his childhood experience, and the events of 9/11, taught him about how vulnerable U.S. civilians are to being rounded up and detained when the nation is under threat: “You think it won’t happen again? Yeah, it can.”

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.