Juneteenth commemorates the date, June 19, 1865, when Union Army general Gordon Granger announced the end of slavery in Texas. Although Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863, it took nearly 2½ years for the enforcement of the proclamation to take effect in Texas, one of the last states to come under control of the Union Army. Formerly enslaved individuals in Galveston, Texas, celebrated Granger’s announcement, and those celebrations grew throughout the state and ultimately the nation in the form of “Jubilee Day,” “Emancipation Day,” “Liberation Day” or, simply, Juneteenth.

While I celebrated Kwanzaa the very first year it was proposed, I was not an early adopter of Juneteenth. By the early 2000s, when Juneteenth was becoming fixed in popular Black culture, I’d already immersed myself deep enough into Black history to make me question how much I wanted to embrace the day.

As much as I recognize the historical significance of Juneteenth and its importance for African Americans, it’s a problematic holiday for me. It contributes to an outsized and unearned legacy for Lincoln’s role in ending slavery. It commemorates a time when the United States government began pulling back from the only true attempt ever made to bring about racial equity and racial justice. And it celebrates the ending of one brutal form of racial oppression without simultaneously acknowledging the other forms of equally brutal racial oppression that quickly sprang up in slavery’s place.

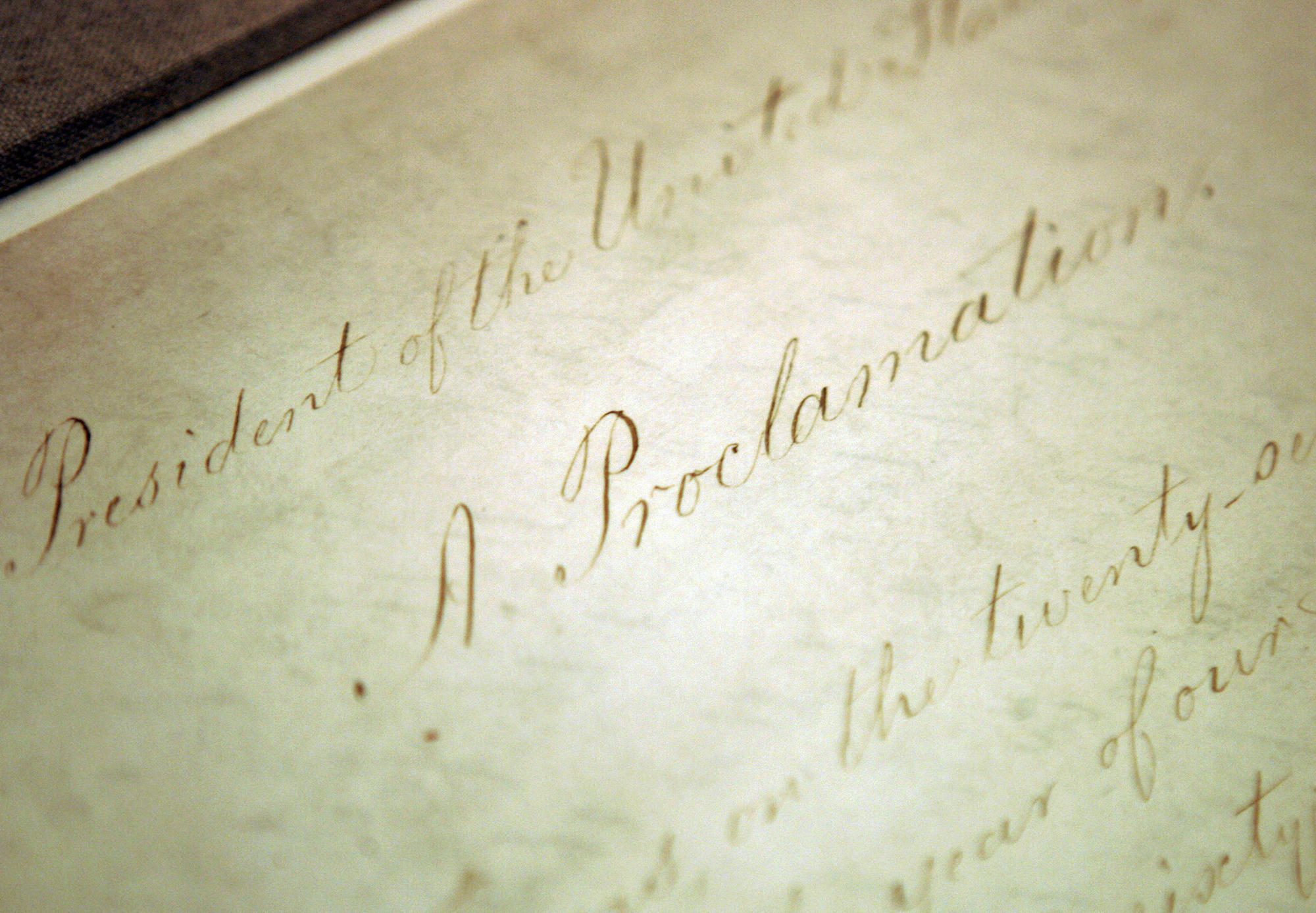

A misunderstood document

Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation may be one of the most misunderstood documents in American history. Contrary to popular belief, the proclamation did not officially free a single slave. It sought to free slaves only in the 10 Confederate states at war with the Union, but the Confederacy never recognized Lincoln’s authority. So while slaves in the South were technically free under the proclamation, they were left to their own devices to escape to Union-held territory. Meanwhile, nothing had changed for slaves in Northern states, where they were still considered chattel. That’s why even after the first Juneteenth, slavery still existed until the 13th Amendment abolished slavery throughout the country.

Critics were quick to point out the hypocrisy of what appeared to be more of a military strategy on Lincoln’s part rather than a sincere effort to end slavery. On Oct. 11, 1862, the London Spectator decried the proclamation as “half consciously pressing along a road which ends in emancipation.” It continued, the “principle asserted is not that a human being cannot justly own another but that he cannot own him unless he is loyal to the United States.” The tepid nature of the proclamation is one reason why, throughout the 19th century, Frederick Douglass and other abolitionists continued to commemorate Aug. 1 rather than Juneteenth as Emancipation Day. Aug. 1, 1834 was the day that Great Britain put into effect a much more strongly worded proclamation that freed all slaves anywhere in the British Empire.

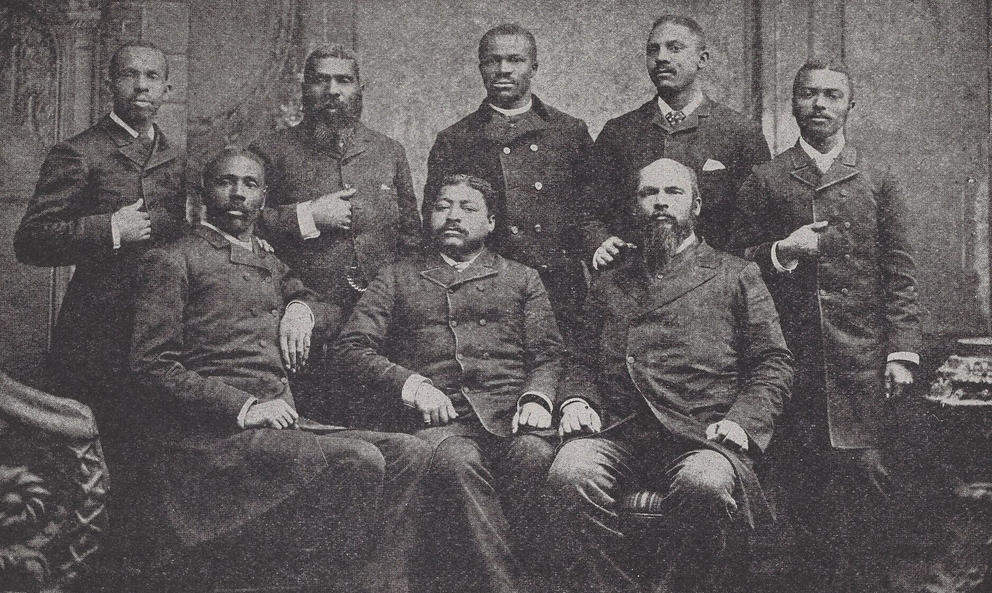

A studio portrait shows African American members of the General Assembly from 1887 to 1888. Seated, from left to right, are Alfred W. Harris, of Dinwiddie County; William W. Evans, of Petersburg; and Caesar Perkins, of Buckingham County. Standing, from left to right, are John H. Robinson, of Elizabeth City County; the author's relative Goodman Brown, of Surry County; Nathaniel M. Griggs, of Prince Edward County; William H. Ash, of Nottoway County; and Britton Baskervill Jr. of Mecklenburg County. (University of Virginia Special Collections)

Abolitionists were hoping for more, but feared what was coming from Lincoln. Months before signing the proclamation, Lincoln wrote to New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley, “My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery.” The welfare of Black Americans was not Lincoln’s paramount objective in 1863. So perhaps it is not surprising that Lincoln had no real plan for the millions of newly freed slaves in the Confederacy other than to join the Union Army, or find jobs for reasonable wages, while abstaining from all violence.

The Confederacy, by contrast, actually did have a plan for what to do with Black slaves if they prevailed in the war. Judah Benjamin, Jefferson Davis’ secretary of state, laid out a path for slaves that included “[c]autious legislation providing for their ultimate emancipation after an intermediate state of serfage or peonage.” Some would argue that the North won the Civil War, but Black Americans ultimately ended up with the South’s blueprint for emancipation.

Recognizing that Lincoln had no plan, Union Gen. William T. Sherman devised one with the help of a group of Black ministers. Called Special Field Orders No. 15, and popularly known as “forty acres and a mule,” Sherman’s plan, which Lincoln eventually endorsed, confiscated land from southern plantation owners and allocated it to newly freed slaves. Nearly 1 million acres of prime farm land in the coastal South would be redistributed in this way. By the time of Lincoln’s assassination, in April 1865, tens of thousands of freed Black men and women had been allocated land and began settling on it in what appears to have been America’s first sincere, large-scale attempt at reparations for slavery.

But the bullet that ended Lincoln’s life also ended land redistribution. About the time of the first Juneteenth celebration, Andrew Johnson, who by then had assumed the presidency, rescinded Special Field Orders No. 15, returning the land to white Southern planters. It fell to a Union general and head of the Freedmen’s Bureau, Oliver Otis Howard (for whom Howard University is named), to deliver the news from Washington to ex-slaves on Edisto Island, South Carolina, that they would be evicted and their land returned to former slave owners. An old Gullah woman, in the back of the crowd that day, listened intently. As the general struggled for words, she found her voice in the Sea Islands’ version of a spiritual, “Nobody knows de trouble I've had / Nobody knows but Jesus / Nobody knows de trouble I've had / Sing Glory hallelujah!” Howard, reports from the time suggest, broke down and wept.

With Lincoln dead, and Johnson as president, the best chance at reconciliation and racial justice in the history of the United States had slipped away. As the famed historian Lerone Bennett observed in his book, Black Power U.S.A.: The Human Side of Reconstruction, “[T]he allocation of forty acres of land to every adult freedman would have created a democratic infrastructure that would have changed the course of American democracy.”

Little known and never reported is that Sherman, the Union general who worked with Black ministers to devise the reparations scheme and a man often lauded as a champion of Black Americans, later wrote to Johnson that he, Sherman, provided “merely” possessory land titles to newly freed slaves. They were good only as long as the Civil War lasted. He wanted ex-slaves to believe they owned the land until a victorious North could figure out what to do with them. What appeared to be a plan for racial equity was actually just another ruse perpetrated by the federal government on Blacks.

White backlash, then and now

The year of the original Juneteenth celebration, 1865, ushered in a period of U.S. history known as Reconstruction, when former slaves took the reins from former slave owners in statehouses across the South, and even in the U.S. Congress. In 1872, P.B.S. Pinchback briefly served as governor of Louisiana, the first Black man to serve in the role in any state in the country. In 1870, Hiram Revels represented Mississippi as the first Black U.S. senator. And in 1875, Blanche K. Bruce began a six-year tenure as a senator of the same state. In all, an estimated 2,000 Black men held some kind of elective office during Reconstruction, my relative, Goodman Brown, a state representative from Surry, Virginia, among them.

State constitutional conventions run by the formerly enslaved not only rewrote state constitutions to eliminate slavery, but also to include voting rights, civil rights, greater diversity in politics, wealth redistribution, taxation reform, prison reform, universal free education, women’s rights, care for the indigent, expansion of credit and the creation of social safety nets. All of which sounds more like the progressive politics of the 21st century rather than the politics of the immediate post-Civil War era.

Reconstruction, however glorious, was also fleeting. By the 1880s, a white backlash ensued and a new period of restoration commenced. White men disenfranchised Black Americans through literacy tests and property requirements and used violence to reclaim what they perceived they had lost in the preceding years. Black Codes, the Ku Klux Klan and Jim Crow laws all grew out of this era.

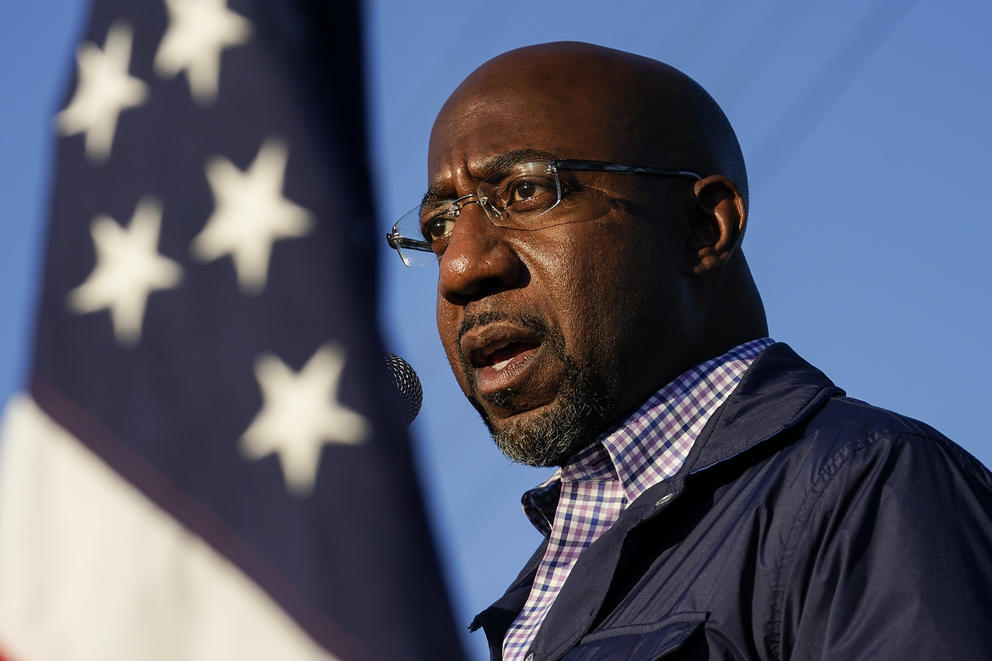

A central objective of the violence and racial terrorism of the period was to intimidate Blacks so they would not vote and, therefore, could not remain in office. For this reason it is hard to consider the history that flowed from the original Juneteenth and not think about contemporary Republican voter suppression bills in Georgia and many other states with precisely the same goal of keeping Blacks, and other people of color, away from polls, making it easier for Republicans to win.

After the Rev. Raphael Warnock won a runoff election this January, becoming the first Black Democratic senator from the post-Civil War South, Georgia Republicans rushed through a massive voter suppression bill, which Gov. Brian Kemp then signed. Other state Republican delegations followed suit, including here in Washington state, where Republican are currently seeking to roll back mail-in voting. “Jim Crow in a suit and tie” is what Stacey Abrams has called this modern-day restoration effort.

For me, Juneteenth is loaded with a troubling history that I’m not sure can be unpacked over a barbecue grill, in a street fair or during a day off from work. W.E.B. DuBois described the time period of Juneteenth succinctly, “The slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery.” Each of DuBois’ three moments are inextricably linked. We need a holiday that commemorates them all.