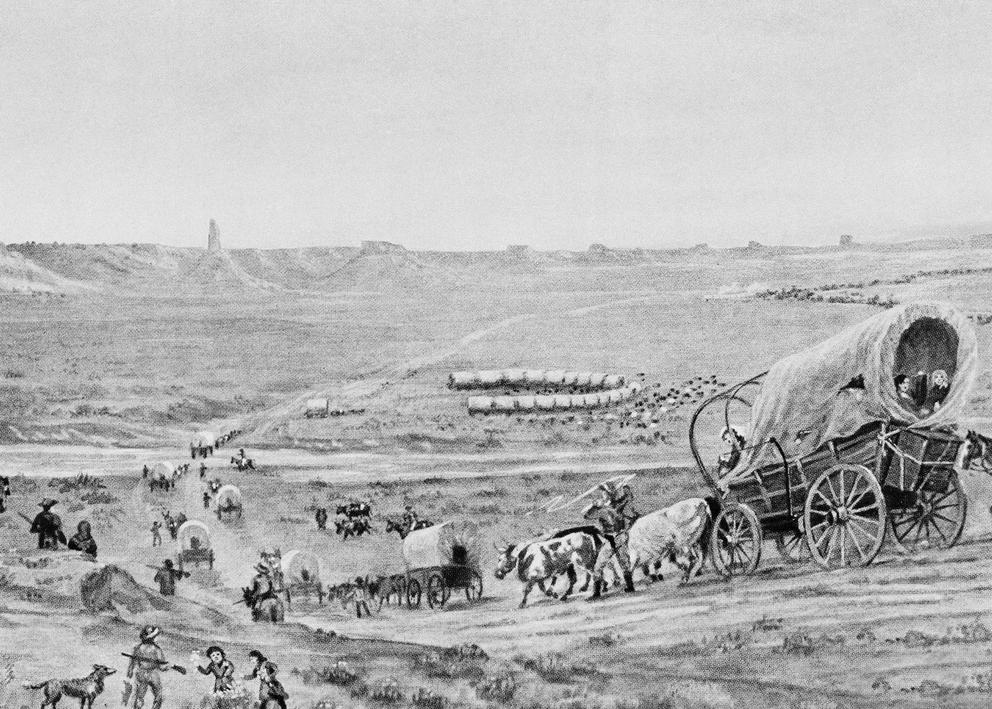

But one doesn’t need to look farther than the Pacific Northwest and Seattle to find examples of racism in decision-making about our roadways and their impact. In fact, you can go back to the Oregon Trail, effectively an interstate highway for people, wagons, oxen and horses. It was forged by white Americans to settle this part of the country.

Few Black people came out on the trail, and the few who did were enslaved, with a few exceptions. The trail was a nearly all-white affair by design. The whole incentive for settlers to come here was to homestead and receive free acreage in exchange for cultivating the land, which was taken from Indigenous peoples in the region. People of color were in turn prohibited from acquiring land by these means. In addition, the Oregon Territory where they arrived, and later the state of Oregon, passed exclusionary and punitive laws targeting Blacks, Natives, Pacific Islanders and Asians. The conscious intention to create an all-white space was explicit.

With that kind of beginning, it’s no wonder that scholars can show how the expansion of the interstate highway system was influenced by racist policies. In many cities, highways were often used to clear “blight” by displacing the poor and communities of color. And they were sometimes used as buttresses to solidify divides between white and nonwhite neighborhoods.

Another example of driving growth while promoting exclusion, similar to the pattern established by the Oregon Trail, came in 1940. That year, crews finished construction on the Lake Washington floating bridge, a last link connecting Seattle to the East Coast as part of a transcontinental highway. It opened a new era of suburban settlement and industrial expansion, and encouraged a car-centric Eastside catering to white developers.

Among them was Miller Freeman, a main proponent of the bridge. He was a Seattle publisher and businessman who served as president of the Lake Washington Bridge and Highway Association and played a leading role in the business community as head of the Anti-Japanese League, active in the early 20th century. Freeman worked diligently to drive out Japanese people. He fought against Japanese immigration, land ownership and the right of Japanese people to participate in the workforce. He criticized the railroads for an influx of Japanese workers coming to the region. In 1920, he argued vigorously against what he called the “peaceful invasion” of the Japanese that had “injured” white workers, a continuation of anti-Asian racism and violent exclusion that had taken root on the West Coast.

Miller later supported the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II and opposed their resettlement afterwards. The productive Japanese farming community in what were once the fertile strawberry fields of Bellevue was displaced by development plans the Freeman family had for a new downtown Bellevue.

Freeman, son of a Confederate soldier, was lionized in the local press when he died in 1955. His impact on infrastructure, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer wrote, was profound: “[I]t is very difficult to look anywhere in the burgeoning region without seeing some abstract idea … in which he did not have a hand and mind.”

Simply put, Freeman’s desire for racial exclusion was baked into his vision for the Eastside and “his” consequential bridge.

The highway expansion drove postwar growth, but at a huge cost. When local leaders decided to expand Interstate 90 in the 1970s and ’80s, many dismissed concerns from communities worried about the potential impact of the expansion, some of which had distinct unequal and racial overtones. The I-90 expansion battle, which included talk of a second bridge, additional tunnels and a wider freeway, is a case in point. The project ran into resistance on affluent Mercer Island, where mostly white residents objected to a bigger highway through the heart of their community. Bowing to pressure, officials eventually agreed to lid the highway as it passed through the more populated commercial center and to build a public park on top (what is now Aubrey Davis Park).

The city of Seattle argued for the same treatment for the Central District as Mercer Island received. It said a longer lid in the Rainier Valley, a park and the replacement of the old Colman School with a new one were needed to mitigate the bigger freeway’s impact. It took pushback from neighborhood activists and the city for Seattle to get treatment akin to Mercer Island’s. Subsequently, the lid, Sam Smith Park, a new school, pedestrian walkways and both bike trails and a bike tunnel through the bridge were successfully negotiated. Gary Gayton, the sole Black member of the city’s I-90 negotiating team, said the state resisted mightily until arbitration resulted in a win for the city.

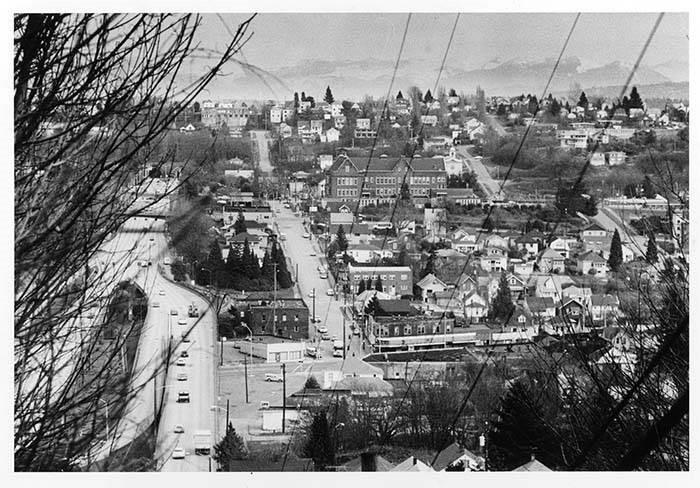

This 1983 image of Yesler/Atlantic and Judkins Park neighborhood was taken facing east towards the Cascade Mountains. Rainier Avenue South runs north-south along the bottom of the frame. I-90 runs along the left edge of the frame, heading east, paralleled by South Atlantic Street in the center of the frame. The large brick building in the center of the frame housed Colman Elementary School (later Thurgood Marshall Elementary School) on Atlantic Street and 24th Avenue South from 1912-1979, and since 2008 has been the home of the Northwest African American Museum. (MOHAI)

The Chinatown-International District has also seen successive disturbances by highway and other huge public projects. There was protest and resistance to Interstate 5 through downtown, which saw the destruction of low-income housing and separated downtown from the hill neighborhoods. Arguments for a lid went unheeded. The massive interchange between I-5 and I-90, and the construction of the Kingdome in the 1970s, threatened the district's cultural identity and viability, and catalyzed activists to demand mitigations. The residents of the Chinatown-International District have often felt like a dumping ground for Seattle’s development.

Recently, I participated in a panel discussion with Warren King George of the Muckleshoot tribe and Lorraine McConaghy of the Museum of History and Industry, on the history of Eastside transportation and development. The panel was sponsored by the Greater Redmond Transportation Management Association, which is promoting greater transportation equity on the Eastside. The future development of Link light rail from Seattle to Bellevue and Redmond is an opportunity to reflect on how the car-centric Eastside can serve communities more sustainably and fairly.

In the 1970s and ’80s, after open housing was put into law in Seattle, the Lake Washington bridges eased white flight to the suburbs. Voters, led by suburbanites, turned down mass transit ballot measures in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Kemper Freeman, Jr. of Bellevue Square fame and grandson of Miller Freeman, was a strong opponent of our current light rail. The Eastside has diversified significantly in recent years, but urban growth will likely increase the need for more equitable access across the region.

Transportation and equity issues are deeply connected. As the Eastside and related suburbs become increasingly urban and vital, dealing with the legacy of race on the ground is important. Rail, transit, bike and pedestrian access and related development patterns are clearly a crucial part of the equation, as are more environmentally sustainable and less polluting transportation and energy.

As Buttigieg said, racism was built into some of our highways. It isn’t the whole story, but fixing that legacy and not repeating its mistakes is crucial. Our infrastructure is a concrete reflection of who we are and who we will be in the future.