I am the youngest of four children, six years after my last sibling, most likely an accident. But even until the last day, she never admitted it.

“I always wanted four children,” she told me, tubes coming out of everywhere: the port in her chest, the oxygen in her nose, the IV in her arm.

On Sunday, she had gone into the emergency room. By Thursday afternoon, she was dead.

My mother was one of 24 people in Washington state who died from COVID-19 that day, joined in death by 1,141 others across the country.

As the holidays approach, with rising pandemic fatigue, social isolation and general exhaustion, families are planning to see each other in what has seemed like the longest year.

Yet this may become the deadliest holiday.

Ed Yong, a science writer at The Atlantic, framed the stakes of our moment very simply. Referring to charts that show the time between positive cases and hospitalizations, he tweeted, morbidly: “Another way to think about these lags is that some of the people who are infected on Thanksgiving will enter the hospital in the middle of December, and the morgue around Christmas.”

I can’t stop thinking about it. Laugh, eat, drink and unknowingly contract COVID-19. Instead of holiday gift shopping, you call family to tell them you’ve been hospitalized. By New Year’s Eve, your family is tasked with the most difficult to-do list of all time, something I’m doing right now: calling crematoriums, touring cemetery plots, writing obituaries.

The third wave we keep hearing about? It’s here. On the day my mother died, she was one of more than 67,000 people who were hospitalized in the U.S. Less than a week later, that number has crawled steadily past 75,000. Skeptics point to the third wave as a result of more testing, but the data isn’t exclusive to positive tests. It applies to deaths, as well.

All of the naysaying rings hollow, anyway, when you’re strapping on full protective gear to hold your mom’s hand for the last time. But my family and I were fortunate, a word I never thought I’d use to describe Nov. 12.

I had called Spokane’s Sacred Heart Hospital’s intensive care unit. The nurse told me that end-of-life protocol for COVID-19 patients at Sacred Heart allows for only two visitors. Texting the news to my siblings, we all silently wondered who those two would be.

But an exception was made. We were allowed to rotate through, each of her four children and her husband of almost half a century, two in the room at a time. My dad, who had also recently tested positive, was allowed to sit next to his wife and hold her hand, while my siblings and I filed in one by one.

A hospital staff member told me it was my turn. Someone at a desk took my temperature and asked for my name to write on a visitor’s badge. I don’t know how he heard me. The tears had already started, my voice was shaky, my mind a blur.

Up a flight of stairs to the ICU. I looked into my mother’s room, surrounded completely by glass, and broke down. I was shaking, unable to hold apart the rubbery bands of my N95 mask. A nurse gently unwound them, adjusted my mask, tied my paper robe behind my back. Next were gloves, then goggles. She told me, “You have it in you. You have it in you.” I can’t imagine how many times she’s had to tell someone that, how it affects her, all the death hovering nearby for so many shifts, for so many months.

My sister left the room. It was my turn.

It felt like awhile, my presence in that room, but it was probably less than 20 minutes. She was tired, struggling to breathe. I was the third sibling to visit, still one to go. I kept one of my hands locked in between hers, freeing the other hand to tilt my goggles up so I could see, the humidity of my tears fogging the plastic, continuously, relentlessly.

I tried to thank her for years of cooking, homeschooling and attending sporting events. Impossibly, I tried to articulate my gratitude for her care, for her endless love.

She was the queen of traditional American cooking: casseroles and buttery biscuits and meatloaf and banana bread. On our birthdays, we were allowed to choose a meal and a cake, requesting amateurish yet elaborate ones shaped like school buses and pigs and superheroes. I always chose tuna fish rolls as my birthday dinner, a recipe that I later learned was uncommon. When friends laughed and asked what they were, I explained that my mother rolled tuna fish inside dough, much like a cinnamon roll, baking them then finishing them off with a layer of melted Velveeta cheese.

She had homeschooled all four of us kids at some point. She taught me to read and let me get my own library card when I was 4. She attended every one of our many sporting events, basketball and volleyball and track and soccer, however boring and long and cold they were. She was there, cheering alongside my dad.

She was the mediator in our family, patient and kind and level-headed, ready to calm the storm during family crises.

She thought, rightfully, that I was the funniest of her four kids.

Breathing through her nasal tubes, she told me I was her little imp. She asked about my dog and my partner, whom she never met, and never will. We laughed. We sat in silence.

There are no rules for this. How long does one say goodbye? A horrible, nauseating feeling welled up inside me. I knew she was tired, and sick, and ready. I didn’t want to cut our last encounter short. Waves of anxiety rolled over me. She said she wasn’t scared, wasn’t nauseated anymore. And as a strong Christian, she said, she was ready to meet Jesus.

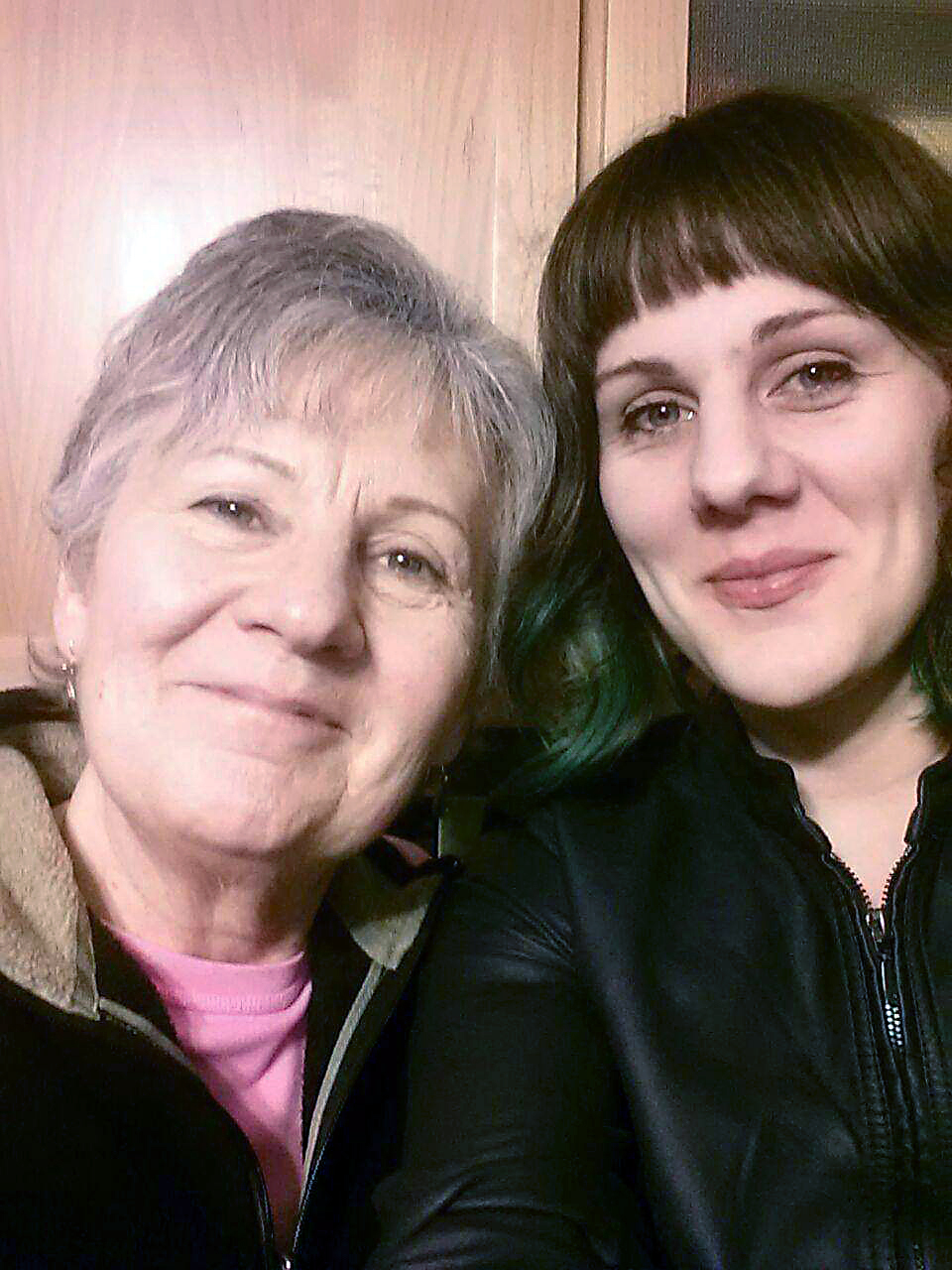

I asked if I could take a picture with her, one last photo, something I still don’t know if I want to remember. I dwarfed her in my PPE. She commented at how small she looked when my dad showed her the photo.

“Don’t post this on Facebook,” she joked. “I won’t,” I promised. “Well, make sure your dad doesn’t either,” she chided, knowing my dad’s proclivity for oversharing on social media.

She had been in a parasitic relationship with leukemia for 15 years. It came in waves, but was always defeated by chemotherapy. Her last bout of chemo wasn’t as successful, and it left her weak. In early October, doctors discovered she had a serious but treatable heart condition. She started oral chemotherapy, taken by pill, which usually yields promising results while lessening side effects. She was certainly in the at-risk category for contracting and dying from COVID-19.

But because my mother never complained, we didn’t have any idea how close she was to the end. She texted the family an update on her oxygen at 6:25 p.m., the day before she died: “Started out at 100%, but now down to only needing 70%. So good.” Extremely low oxygen levels brought her to the ER in the first place. We were relieved.

And then my sister’s sister-in-law — herself a nurse, someone who knew nurses in the ICU — told us that she was on a nonrebreather mask, which covers your entire nose, mouth and chin. It’s used only in emergencies. Not sustainable, they said.

Those ICU nurses and aides and doctors, whom I will never forget, didn’t show how tired they were that day. But collectively, they were exhausted.

At Gov. Jay Inslee’s Nov. 15 press conference, Sacred Heart ICU nurse Clint Wallace pleaded with Washingtonians to “put aside their political and financial motives and follow the directions of our health care experts.”

Wallace spoke of the burnout among hospital staff. “It's been difficult for staff for so long, and we have used our emotions, our physical abilities, our vacation time for the last eight months,” he said. “We need help. We need everybody's help."

Yong, the journalist at The Atlantic, wrote about the disproportionate burden of ICU patients on hospital staff: respiratory therapists, dialysis technicians, nurses responsible for drug administration, six people just to flip a patient over. “An ICU nurse can typically care for two people at a time, but a single COVID-19 patient can consume their full attention,” he wrote.

I had brought doughnuts for the ICU staff the day before my mom died, not knowing how intimately I would come to know them a day later as I cried and shook and struggled to speak.

Since then, the sadness has been immeasurable.

I recently attempted a relaxing bath: a bath bomb, a candle, some soulful music. But watching the colored water swirl, all I could think of was my mom’s life draining away. Thoughts of her permeated everything I did.

I'm finding it difficult to convey how painful death feels. If I could, maybe I could convince you to stop planning Thanksgiving.

We know the science, we see the spikes, we’ve read that a quarter million people have died from this disease. Wearing masks, sanitizing and staying outdoors can greatly stop the spread of COVID-19. You don’t even have to skip the holidays: find unique ways to celebrate.

When planning festivities, I beg you to remember my mother, and to think of your own. I can’t make that decision. My mom won’t be here for Thanksgiving, or Christmas, or my birthday, or my wedding.

But you have that choice. You are preserving the opportunity for next year, and the many years to come.