The 1912 presidential race was anything but boring. A week before the vote, Republican incumbent William Howard Taft’s running mate perished of kidney disease. Former President Theodore Roosevelt, raising the banner of the Progressive “Bull Moose” Party after losing the primary to Taft, suffered a mid-October assassination attempt by a man who reasoned that “any man looking for a third term ought to be shot.” (Roosevelt went ahead with his campaign speech despite the bullet embedded in his chest.) Democratic New Jersey Gov. Woodrow Wilson sustained a scalp wound in an automobile accident three days before the election. And trade unionist Eugene Debs won 6% of the popular vote, still the strongest showing for a socialist in a U.S. presidential election.

This is the third column in a series on Amazon and antitrust. Read parts one, two, four and five.

But quite apart from all that, the 1912 election is worthy of our attention because the burning political question of the day was what to do about the great trusts. Last week, I explored, briefly, the prehistory of antitrust, the perils and the benefits of bigness, and why drawing legal lines through this territory is inherently challenging and inevitably controversial. So how was it done?

The cornerstone of U.S. antitrust law is the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, named for Sen. John Sherman of Ohio (and younger brother to the general of Civil War fame). The language was sweeping: “Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, is declared to be illegal.” The act also prohibited monopolization or attempts to monopolize any aspect of interstate commerce. But what exactly counted as “restraint,” or an “attempt” to monopolize? The broad-strokes language left much up to interpretation.

For the first decade of the Sherman Antitrust Act, the robber barons weren’t exactly running scared. In 1895, the Supreme Court ruled that the American Sugar Refining Company’s 98% market share didn’t violate the law, because the company engaged in the manufacture of sugar, not directly in interstate trade. In fact, the act incentivized mergers, because agreements between independent corporations aroused more suspicion than the activities of a single large firm. As far as trustbusting was concerned, it seemed a dead letter.

Union busting was a different matter. In 1894, when members of the American Railway Union refused to handle Pullman cars in solidarity with abused workers at the Pullman Palace Car Co., where the train cars were built, the strike was broken by an injunction that invoked the Sherman Antitrust Act — the union, after all, had conspired to interfere with the transport of goods from state to state. Debs, among other ARU leaders, was found in contempt of court for violating the injunction. He devoted his six months in prison to reading, including Karl Marx’s Capital, and emerged a committed socialist.

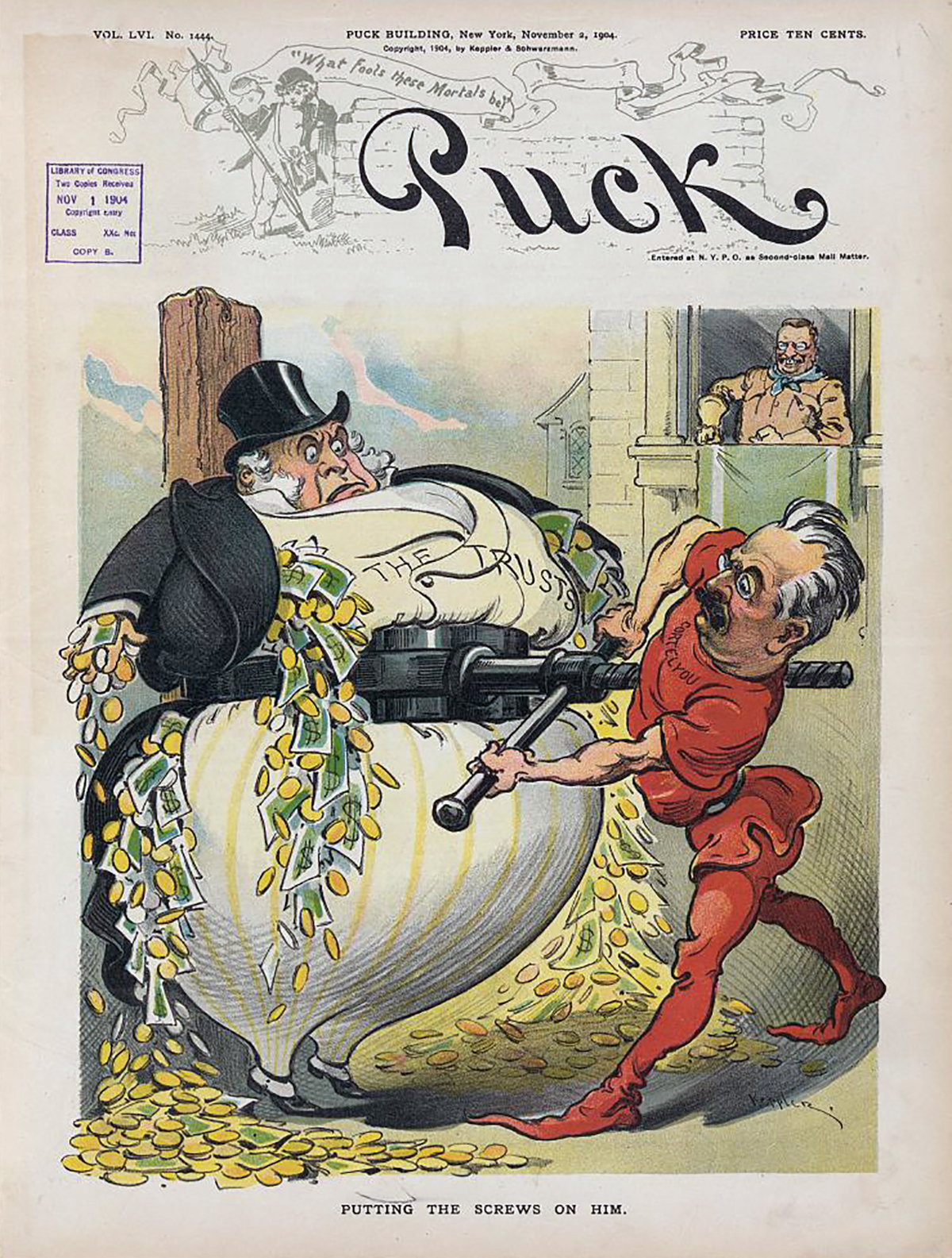

A tidal wave of consolidation swept through the U.S. economy from 1895 to 1904. Farm equipment and cattle, cigarettes and whiskey, linseed oil, cotton oil, electricity and steel — one-time rivals joined together until each market was effectively dominated by a single entity. “The great merger movement” multiplied complaints of monopolistic abuse, and by the time muckraking journalist Ida Tarbell’s serialized exposé of Standard Oil began appearing in McClure’s magazine in 1902, the public was hungry for action.

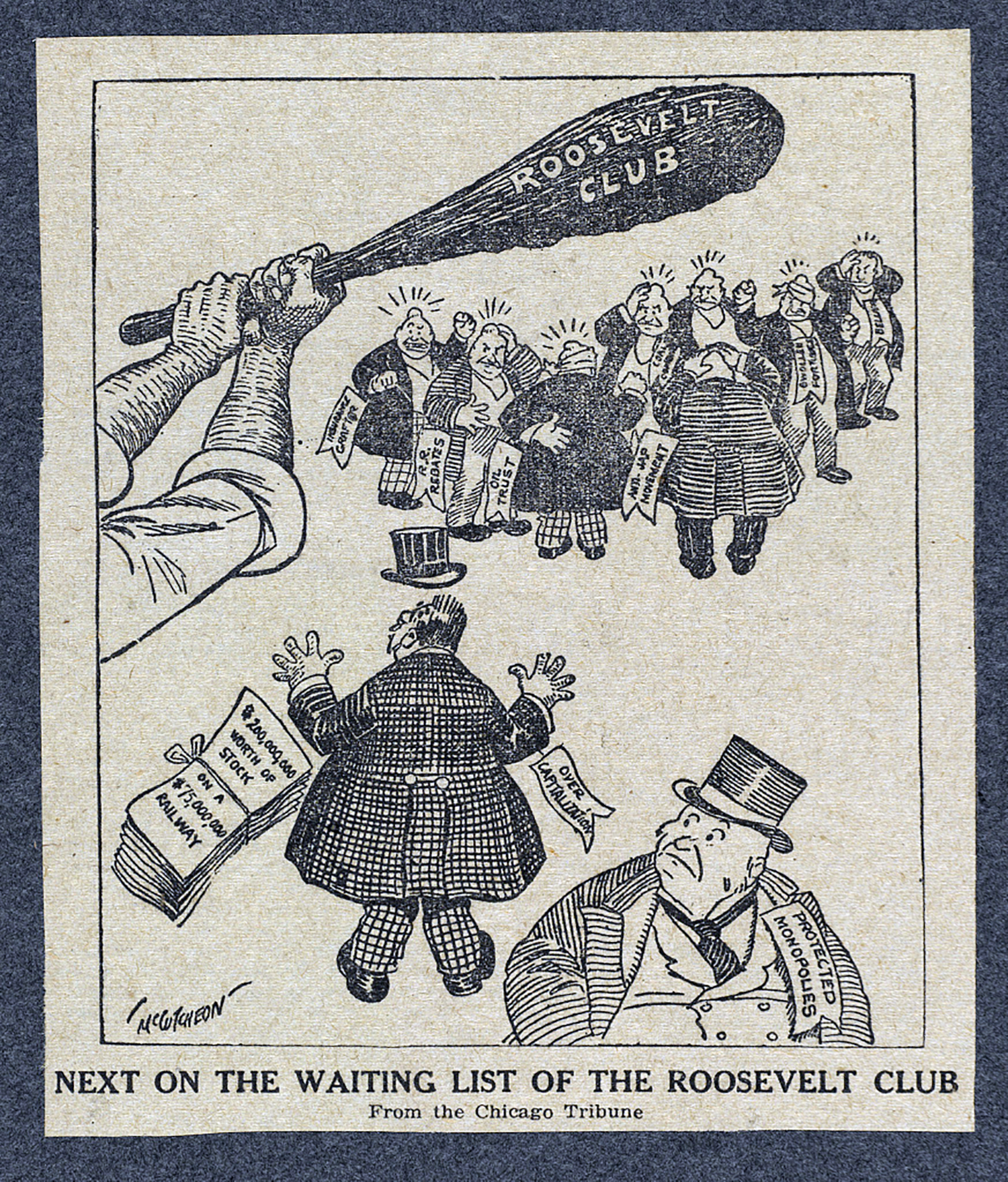

Roosevelt never went as far as progressive trustbusting advocates wanted, but during the years of his presidency (1901-1909), his administration initiated over 40 antitrust lawsuits, including high-profile cases against the Northern Securities railroad company, the Beef Trust, American Tobacco and, of course, Standard Oil. Roosevelt’s successor, Taft, outdid him, initiating more than 70 antitrust actions in his four years. At last, the Sherman Antitrust Act was wielded effectively against the great trusts.

And that brings us up to the 1912 election. It was, according to Daniel A. Crane, professor of law at the University of Michigan, “by far the most consequential for U.S. competition policy to date.” (And also “arguably the most melodramatic in American history,” but Crane was writing in 2015, so we can forgive that.) At issue was not merely how best to maintain a competitive economy, but whether a competitive economy was desirable at all.

Taft ran as a trustbusting champion. He had, in fact, had a large hand in reinventing the Sherman Act way back in 1899, when, as a U.S. Court of Appeals judge, he ruled against a pipe manufacturers’ association for rigging bids. Taft now saw aggressive antitrust enforcement as the best way to save the capitalist market and avoid a slide toward socialism.

Roosevelt, on the other hand, had grown disenchanted with the parade of antitrust lawsuits — and with his erstwhile ally, Taft, who he now declared had “the brains of a guinea pig.” He believed the great combinations had come to stay, and the answer was not to break them up, but to regulate them. Even during Roosevelt’s presidency, he often favored this strategy; he supported legislation that imposed rules on the railroads, restricting the granting of rebates and empowering the Interstate Commerce Commission to set maximum rates. By the time Standard Oil was finally broken up, Roosevelt disapproved the move. Now he made the case for a “New Nationalism,” including far greater federal supervision of big business — for which, in some quarters, he was denounced as a “communist agitator” and a socialist.

Then there was Debs, the actual socialist. Debs believed the concentration of industry to be natural and inevitable. The call to smash up the great trusts was quixotic, he argued: It was “but a repetition of the cry of the weavers and spinners of England against the introduction of the machinery which threatened to displace them,” or “the protest of the stage coach against the locomotive and of the pony express against the railroad and the telegraph.” Once, competition had been constructive; now it was only destructive. The real choice was “between industrial despotism and industrial democracy, that is to say, between capitalism and Socialism.” The workers employed by the great trusts must organize, Debs argued, and ultimately take them over in the name of the people — the trusts must be not only regulated, or even nationalized, but socialized.

Wilson rounded out the field. Like Taft, he proclaimed the virtues of competitive markets. In fact, he promised to go further than the Republicans in enforcing and strengthening antitrust laws, but he was wary of heavy-handed regulation of the sort Roosevelt championed. Wilson also took a strong stand on another, and related, contentious issue of the day: protective tariffs, which insulated U.S. companies from foreign competition. Lowering the tariff, Wilson argued, would make it possible to enjoy the efficiencies and other advantages of bigness without sacrificing the social benefits of competition — competition between the industries of the various nations would thrive, and fewer antitrust actions would be necessary.

How did it all end? Roosevelt ran one of the strongest third-party campaigns in history, but split the Republican base, and Wilson and his “New Freedom” prevailed with 42% of the popular vote. Strongly influenced by his economic adviser, Louis Brandeis, Wilson set out to implement his vision of “regulated competition.” He lowered tariffs; established and empowered the Federal Trade Commission to enforce antitrust laws and protect consumers; and sponsored the Clayton Antitrust Act, which went further than the Sherman Act in specifying prohibited conduct — and also exempted labor unions from antitrust suits, declaring strikes, boycotts and picketing legal under federal law.

It was one way forward. But the questions underlying the antitrust debates of 1912 were far from definitively resolved. Next week I’ll bring this story up to the present day.