The teenagers were 16 and 17 when, along with their then 13-year-old younger brother, Joseph, they entered the camp known as the “Jungle” with the intent of robbing a prolific drug dealer. Joseph was prosecuted in juvenile court, convicted of murder and assault charges, and, in May 2018, sentenced to eight years in juvenile detention. Next month, during a sentencing hearing that arrives after two previous mistrials, the older brothers’ attorneys will try to convince a judge that, because the teenagers’ brains were not fully developed, their actions should be judged less harshly than if they were adults.

Given the severity of their crimes and the nature of our criminal justice system, it will probably make little difference.

All too often, there is little will to summon the resources necessary to change the trajectory of delinquent children’s lives, and failures in the systems designed to set them on a better path increase the chances they will enter the criminal justice system. When youth commit violent crimes, total war is waged against them to ensure they receive what prosecutors believe are just deserts. In addition to this retributive ethos cloaked in the language of “public safety,” the laws enabling children to be treated as adults for purposes of punishment all but ensure that young people will receive little mercy.

That’s why it’s important to understand what came before the boys committed their crimes.

In 1992, at age 14, I committed a homicide. For this, I became one of the youngest children ever to receive a sentence of life without parole in Washington state. I was a drug dealing runaway, sleeping in cars and abandoned tenements, with little support from caring adults. After 25 years of confinement, it became clear to me that there were missed opportunities to set me on another course. As I wrote in 2018, “Juvenile court judges and social workers saw the need to intervene, but, inevitably, both lacked the necessary resources to do so effectively.”

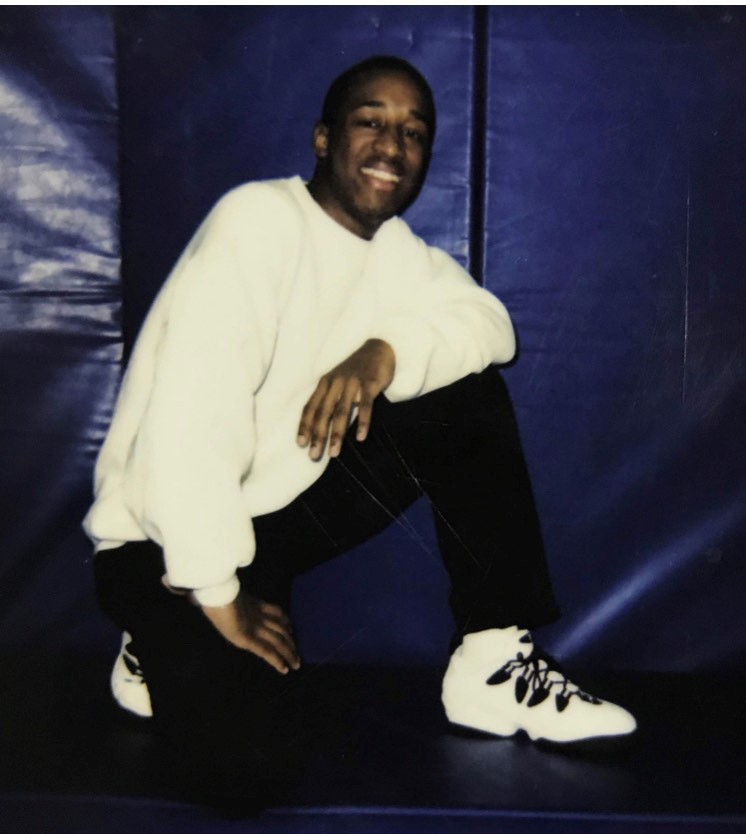

So, too, with James and Jerome Taafulisia, whose lives were burdened by poverty, neglect and instability. Growing up, they were “in and out of foster care, homeless, and exposed to environments and activities no child should ever have to witness or experience,” the community activist Xing Hey has written of the boys. Their life on the streets so affected former juror Irma Fritz that she felt compelled to acknowledge not only the families of the victims and survivors of the shooting, but also James and Jerome. “My prayers are with the families of the two victims, the three survivors, and the two accused brothers, as they’re again reliving this trauma,” she wrote last year in the Auburn Reporter.

Many poor Black and brown teenagers live in environments surrounded by drugs and violence. Some of these teenagers are on the caseloads of employees of the state Department of Social and Health Services, as was the case for the Samoan Taafulisia brothers. What distinguishes James, Jerome and Joseph from other impoverished children fighting off the gravitational pull of delinquency and criminality, however, is that they resided in a notorious homeless encampment.

“[At] the time of the shooting, these three youth were wards of the state who were living together in a tent on the outskirts of the Jungle,” Hey said. “The very system that claimed to support and protect them simply failed.”

To be sure, homelessness and poverty do not make anyone commit crimes, especially murder. That is one of the reasons why, during this summer of unrest, it is unlikely that public officials will be making pleas for these young men to receive mercy. Whatever sympathy is directed toward the chronically poor tends to disappear when homeless individuals negatively impact local business, and especially when they become armed and dangerous.

At that point, all the resources withheld from people of color living on the margins — from anti-poverty investments to meaningful social programs — will be used to remove James and Jerome from society. It is a familiar theme: All the money necessary for retributivists to effectuate their ends is readily available, while those tasked with undoing the systems that ensnare young Black and brown children scramble for resources.

Now, after being tried in adult court, the Taafulisia brothers are staring down a long future in the criminal justice system.

In another time, their fate may have been different. It was once up to juvenile court judges to determine whether juveniles should be tried as adults. Prosecutors could argue that certain offenses merited adult punishment, but before a youth could be tried as an adult, a judge had to consider the defendant’s age, the seriousness of the offense and the prospect of rehabilitation, if the person is convicted. At that point the judge would decide whether the youth should remain under the jurisdiction of the juvenile system or be treated as an adult.

The Legislature stripped away that discretion decades ago, replacing it with a process known as “auto decline,” through which 16- and 17-year-olds are automatically tried as adults for a number of serious crimes.

Long before King County implemented its Equity Impact Review — a process used to identify, evaluate and communicate the impact of policies on equity — it was well understood that this lack of discretion “disproportionately impacts young people of color” and “increases recidivism,” according to the nonpartisan Washington Institute for Public Policy. But prosecutors remain committed to maintaining this arrangement, which aids and abets the school-to-prison pipeline, despite King County’s avowed “need for an explicit racial equity approach in our criminal justice work” touted under its Pro-Equity Policy Agenda.

Established in the mid-1990s, the statute has come under increased criticism. Washington’s auto decline statute, according to a report by the American Civil Liberties Union, “was a product of fears about juvenile ‘superpredators,’ who allegedly were about to cause a huge crime wave.” The report adds: “These fears had an explicitly racial overtone. … Washington’s auto decline law creates significant racial disparity, consistent with studies showing at least implicit bias in that African American youth are viewed as ‘less innocent’ than their white counterparts.”

This strikes at the heart of King County’s stated view of structural racism, which it defines as “the interplay of policies, practices, programs and systems of multiple institutions which lead to adverse outcomes and conditions for communities of color compared to white communities that occur within the context of racialized historical and cultural conditions.”

I became a product of King County’s justice system before policymakers used such phrases as “racial justice” and “systemic racism.”

Looking back on government records compiled during my life as I flowed through the school-to-prison pipeline, I realized that I had “low self-esteem,” I thought that drug use was “normal” and believed I had a “parent-ruined family,” according to a Personal Experience Inventory test administered when I was age 13. Nine months after I took this test, juvenile court records stated that my “family situation is a confused mess,” and that my mother reported she had not seen me in several months and believed I was “living in a crack house.”

The Department of Social and Health Services then confirmed that I was “a runaway, having problems in school, affiliated with gangsters, father has alcohol problem, child needs therapeutic intervention due to parent-child disengagement issues. Child has not been to the dentist since age 11.” Shortly thereafter, I was taken to the King County Youth Detention Center after being arrested for a murder and assault I committed in a housing project.

The Taafulisia boys’ pipeline to the penitentiary passed through a notorious homeless encampment, rather than a West Seattle housing project called High Point, as it did for me. But there are other key differences in our stories. For one, I was not automatically declined. Furthermore, the racialized zeitgeist of “superpredators,” long ago proved inaccurate, did not affect the Taafulisia brothers.

But the key difference between the period when I was given a life sentence and today is that there now exists extensive neurological research demonstrating, as the U.S. Supreme Court has made clear, that juveniles have “diminished culpability and heightened capacity for change” notwithstanding their heinous crimes. It is time for our juvenile justice system to take these developments seriously.

For the sake of equity in the criminal legal system, the time has come for judges to be given the ability to once again consider whether children should have the opportunity to be rehabilitated in the juvenile system. Such discretion would have allowed a judge to determine whether the Taafulisia brothers’ culpability was mitigated by a whole host of important factors — that they were influenced by adult accomplices, as their defense attorneys have suggested; their youth inhibited their ability to extract themselves from a criminogenic environment; they were neurologically primed for heedless risk taking; and they are generally more amendable to rehabilitation than their adult counterparts due to their physiology.

Had a judge considered all of this, perhaps he would have determined the Taafulisia brothers’ case should be handled in the juvenile justice system, as it was with Joseph, the youngest of the three.

Additionally, those most impacted by crime and punishment should be given more opportunities to influence prosecutorial decision-making when it comes to youth offenders. This is especially important for a place like King County, which is endeavoring in its Equity and Social Justice Strategic Plan to eliminate disproportionality in the juvenile justice system and engage communities by sharing information and incorporating feedback. In this instance, empirical data on the racialized automatic decline statute, collected by the ACLU, and community input shared by activists such as Xing Hey could have been presented to prosecutors to demonstrate that the Taafulisia case should be handled differently.

It is this type of engagement that helps build trust between law enforcement and communities of color — a trust that both King County and Seattle have been striving to rebuild.

But neither equity toolkits nor progressive policies are going to change the fate of James and Jerome Taafulisia. It is far too late for that. Seattle will wash its hands of them, two cases of homelessness remedied, then the state will spend millions of dollars providing them, for what will likely be decades of incarceration, with the food and shelter they were deprived of as children.