Nichols is a client at Blue Mountain Heart to Heart, an innovative center that provides drug users from across Walla Walla County with a range of services intended to keep them healthy and alive. With fatal overdoses surging in Washington, that’s a tall order.

Facilities like Blue Mountain that serve small cities and surrounding rural areas are the basis for a model of care known as “health engagement hubs” that the Washington State Department of Health hopes will help address the fentanyl crisis, reduce overdoses and offer a pathway to treatment to those who want it.

There’s a worry, however, that centers like Blue Mountain – and similar programs such as one run by Willapa Behavioral Health and Wellness in Grays Harbor County – might be threatened by restrictive local ordinances that would hinder their work. The sweeping drug possession law passed by the Legislature in May includes a provision that could allow local jurisdictions to limit harm reduction services.

Salina Mecham, CEO of Willapa Behavioral Health, says it isn’t clear yet what that will look like. Her organization took over running a needle exchange and harm reduction program in 2021 after the Grays Harbor County Council voted to close a needle exchange program run by the county’s department of public health.

“Nobody necessarily knows how to interpret it right now,” Mecham said of the new state law. “We’re all kind of holding our breath, waiting.”

According to statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Washington saw the largest increase in fatal overdoses of any state in the U.S. between March 2022 and March 2023, a rise of more than 25%. According to the most recent data available, during the one-year period ending in May 2023, 3,159 people died of drug overdoses in Washington, and 78% of those deaths were from opioids including fentanyl.

Though urban areas such as King, Pierce and Snohomish counties are certainly contributing to this spike in fatal overdoses, rural areas have also been hit hard. According to the Walla Walla County coroner’s office, in the period since January 2022 the county has had 21 fatal overdoses, 16 of them from fentanyl, a level that’s about equal to the state rate.

According to the county coroner’s office, Grays Harbor County during that same period has seen 75 overdose deaths – a per capita rate more than double that of the state as a whole.

These syringe exchange services not only prevent disease spread but connect people who use drugs with a range of counselors, medical professionals and services. While treatment is offered, it’s not a requirement. And this supportive environment, aimed at building relationships with people whether or not they’re in recovery, is sometimes controversial in rural communities.

For instance, though things have settled down after Willapa Behavioral Health took over the syringe exchange site from the county in 2021, in the first year of the exchange, which the organization set up in the parking lot of a treatment center in Aberdeen, it faced picketing protests outside the site and angry comments on its social media pages, says Mecham.

“These are human beings, who have probably endured more sadness and more pain in their lives and are most in need of love,” Mecham said. “And all they’re getting is hate spat on them.”

Health hubs provide more than just clean syringes

Decades of research show that syringe service programs that allow injection drug users to exchange their used needles for clean ones significantly reduce the transmission of HIV and may also slow the spread of hepatitis C. Blue Mountain’s syringe exchange began in 1998. Everett Maroon, the director, said that his organization had initially planned to give out about 3,500 clean syringes each year, but reached a peak of 577,000 exchanged needles in 2019 just prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The long-term trend of decreasing access to heroin combined with the arrival of fentanyl, a cheap, extremely potent drug that can have widely varying dosages in each pill, has led to a national overdose crisis. Complicating matters, fentanyl is generally smoked, so the need for clean syringes has decreased dramatically. Maroon says the number of needles exchanged at Blue Mountain dropped to 432,000 last year, and the center has given out only about 300,000 as of this September.

“So we see this shift into fentanyl, and see the numbers tank on syringe volume,” said Maroon, “at the very same time when the danger is markedly higher for them overdosing.”

That’s worrying, because programs like those at Blue Mountain and Willapa Behavioral Health are much more than simply places to get clean syringes.

“It’s not just about the exchange,” Mecham said. “It’s about relationship building. Because there’s oftentimes a lot of stigma, a lot of shame, a lot of meanness that surrounds addiction. And so it’s really nice when someone is able to come to someone where they can be helpful and have a good rapport with them.”

Willapa Behavioral Health offers free naloxone, a medicine that can reverse opioid overdoses, as well as fentanyl test strips (which were legalized in this year’s state drug possession bill) that can assess whether other drugs such as meth or cocaine contain fentanyl. Willapa also offers medical and mental health care services and can offer referrals to social services, case management or treatment for those who are ready for it.

Blue Mountain’s health hub model also offers small-scale but important medical services. An on-site nurse focuses on wound care and abscesses, which can be common and a source of shame among drug users. In addition, Blue Mountain offers substance-use treatment services in-house or can refer patients to more involved treatment. It also has a case manager who offers clients programs such as Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD), designed to keep low-level offenders out of jail by helping people with mental health services, medical care, food and transportation, job-search counseling, and housing.

The goal is to help drug users find small doses of stability so that when and if they’re ready they can make changes: applying for a job, seeking housing, or getting medical care they’ve avoided.

One employee at Blue Mountain, who asked not to be named because she once dealt with substance-use disorder, helps clients accomplish what would seem to others like simple tasks like shopping or picking up a prescription. “One person, I’m in the process of helping them get their name changed,” she said. “It’s about goal setting and how I can support them in reaching those goals.”

This employee first came to Blue Mountain as an opioid user seeking clean syringes. “The first time I went in there, I thought: This is gonna be weird,” But in fact, she said, the staff was welcoming, and she was also able to seek basic medical care. When she was ready to enter recovery, Blue Mountain was able to prescribe her suboxone, a treatment for opioid addiction that combines buprenorphine and naloxone.

“Our program is designed for people to be at the syringe exchange and say: I want to try this medication,” Maroon said of the on-site treatment services. “They don’t need to wait for two to four weeks to see an assessor.”

In addition, thanks to another provision in the new state drug law, Blue Mountain now legally offers fairly sophisticated analyses of the ingredients found in drug samples. Clients can anonymously drop off a small sample of the drugs they’re using and Blue Mountain does what it can to determine what’s in that sample. In addition to an on-site mass spectrometer, Blue Mountain sends other samples to a lab in North Carolina. The results are posted where clients can find them in anonymity.

Maroon says that he’s seen increases in the potency of fentanyl in those samples as well as a few instances of xylazine, a strong tranquilizer used in veterinary medicine that’s been used illegally by drug users on the East Coast and is slowly gaining ground out West.

As drug users switch to fentanyl, rural harm reduction programs pivot

Because of the switch from heroin to fentanyl, fewer drug users were coming into Blue Mountain for syringes, Maroon says, and as a result not utilizing its other services. To address this, the organization has started to hand out smoking supplies, which Maroon acknowledges are more controversial than syringes, but can help in preventing some health issues and give drug users a reason to engage.

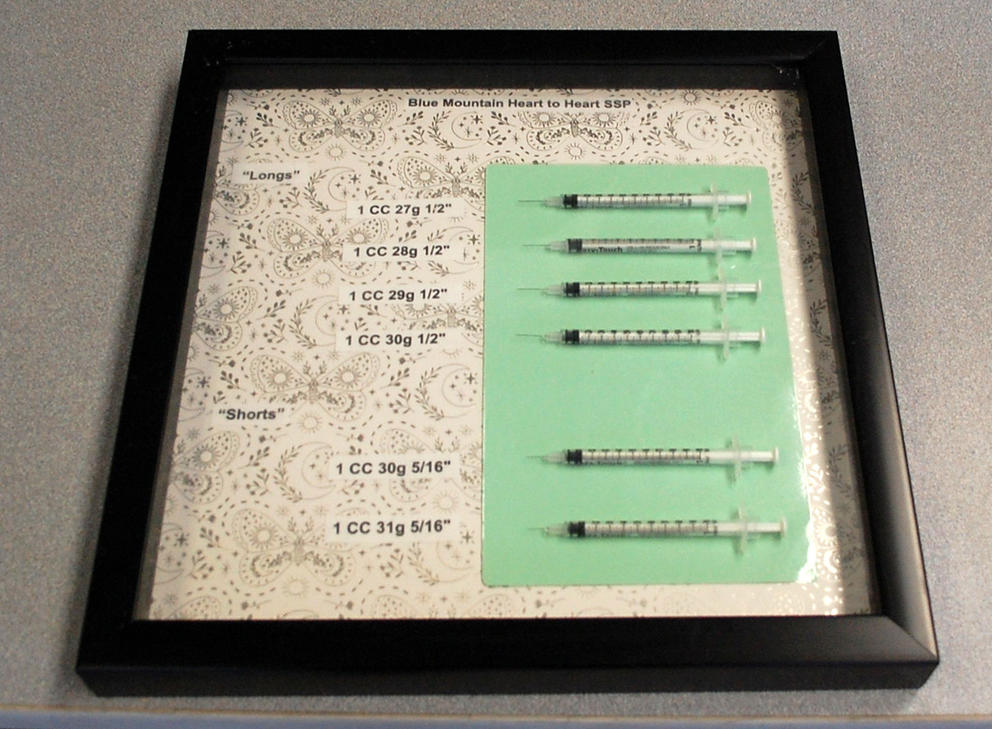

According to Malia Lewis, manager of Blue Mountain’s exchange program, the site offers in its smoking kits two types of pipes, various filters, and medical-grade foil that doesn’t exude chemicals when heated to a high temperature, unlike standard aluminum foil. Although the kits are still focused on keeping people safe and healthy, one of the biggest benefits, Maroon says, is that after several years of declining engagement with drug users, clients are returning and using Blue Mountain’s services. “People came in that we’ve never seen before. People that had stopped coming in started coming back. And people started coming in more regularly,” he said.

All these services are aligned with the Department of Health’s goal to eventually create health engagement hubs across the state so that every state resident is within a two-hour drive of one. The drug possession bill passed this year included $63 million for treatment centers and more pilot health hubs like the ones run by Blue Mountain and Willapa Behavioral Health.

Caleb Banta-Green, director of the Center for Community-Engaged Drug Education, Epidemiology and Research at the University of Washington, said that Blue Mountain has been an inspiration for the state’s health hub model. “In addition to providing drop-in, kind, and life-saving care, we find that Blue Mountain Heart to Heart and several other similar programs around the state spur other community partners to begin providing care, particularly prescribing buprenorphine,” Banta-Green said in an email, referring to a common medication for treating substance-use disorder.

Some residents of these rural communities, however, are skeptical of harm reduction and prefer emphasizing accountability and law enforcement.

Is drug use a criminal-justice problem or a public health concern?

Jill Warne, a Grays Harbor County commissioner who voted in 2021 to end the county’s syringe service program, says that she was concerned that the effort didn’t always require one-for-one exchange and that the program condoned drug use. “When you hand out as many as you want, with no requirements to bring in any dirties, that means that our streets and our parks and public bathrooms are littered with dirty needles,” Warne said. “I thought that it’s more of a public hazard than a health benefit.”

Warne, whose son is in recovery from opioid use, also has friends who’ve died of overdose. She strongly believes that the new state law making drug possession and public use a misdemeanor will help push people into treatment. Though she’s skeptical of harm reduction, she acknowledges that Willapa Behavioral Health’s additional services are helpful. “If they’re trying to get people engaged with going to detox and treatment, that should be the objective,” she said.

Walla Walla has generally been supportive of Blue Mountain, but a satellite site in the Tri-Cities was forced to leave its building in Pasco after Franklin County commissioners voted to evict them in 2019. The site has moved several times amid controversy stoked by local businesses upset with public drug use. Blue Mountain now operates out of a site in Kennewick, in Benton County. It also has a small syringe service facility in Clarkston, in Asotin County, which has so far avoided controversy.

In addition, the City of Kennewick proposed putting restrictions on the Kennewick syringe exchange, including a requirement that each syringe be labeled with the Blue Mountain logo and limiting opening times to daylight hours. After Blue Mountain threatened legal action, the Kennewick City Council declined to pass the restrictions.

Mecham, the director of Willapa Behavioral Health, is concerned about a provision in the state drug possession law that could allow local jurisdictions to put limits on harm reduction programs. Until recently, the legal status of syringe exchanges has been somewhat tenuous in Washington.

A 1992 ruling by the Washington State Supreme Court, Spokane County Health District v. Brockett, established the legality of harm reduction efforts. But there had never been a state law authorizing syringe exchanges until the new drug possession law passed this year, which includes a provision allowing public health organizations to distribute “syringe equipment, smoking equipment, or drug testing equipment.”

However, the same bill also includes language stating, “Nothing in this chapter shall be construed to prohibit cities or counties from enacting laws or ordinances relating to the establishment or regulation of harm reduction services concerning drug paraphernalia.”

Maroon says his organization’s attorneys advised Blue Mountain that the regulations proposed in Kennewick were discriminatory and wouldn’t hold up in court. “They said you’re regulating this in a way you're not regulating anything else in the county.”

Mecham says previous interactions with the Grays Harbor County Council have led her organization to be cautious about starting any new programs. “The community already doesn’t want us there,” she said, “and if we go handing out smoking supplies, I don’t know how they would feel about it.”

Cody Maine, a paramedic with the Walla Walla Fire Department, grew up in a small, conservative community in rural Idaho and has seen the ravages of the fentanyl epidemic firsthand. “It used to be that you could go weeks or months without ever hearing about Narcan [a brand name of naloxone] being given,” Maine said. “But within the last year, we’re seeing multiple overdoses per day.”

While his conservative views first led him to see the distribution of naloxone as condoning drug use, Maine now sees it as an essential tool of public safety, like a fire extinguisher. “My professional duty, and my department’s mission, says that we protect life and property,” he said.

Though he’s skeptical of Blue Mountain’s harm reduction efforts, he’s seeing positive benefits at the site, especially in wound care, which reduces trips to emergency rooms. “There’s certainly awesome knowledge that these nurses have in a clinical setting that’s super-helpful for people dealing with those types of abscesses,” he said. “You’re actually enabling somebody to stay more independent.”

He notes, however, a lack of low-barrier permanent supportive housing in Walla Walla, something that Maroon and his staff also point to as exacerbating the overdose crisis. In addition, one hospital in Walla Walla has closed; there’s no psychiatrist in town specializing in youth care; and the nearest detox facility is two hours away.

Maroon says rural areas and small cities have been neglecting health care and the overdose crisis, pointing to a Washington State University study that found that life expectancy is lower in Eastern Washington than in the rest of the state. “We have more than 200 nonprofits in Walla Walla because a lot of us are doing the work of the local government,” he said.

Mike Nichols, who comes to Blue Mountain regularly to get smoking supplies, drop off a friend’s used needles and receive medical care, is grateful for the services the health hub provides. He’s effusive in his praise as he grabs a box of naloxone and heads back out to the streets of Walla Walla where he’s survived for many years. “I’d do anything I can do to help this nonprofit,” he said, “because they’ve done so much for me in my life.”

Correction: Corrects which government entity proposed putting restrictions on the Kennewick syringe exchange.