Thick files crammed into manila envelopes filled in gaps. Thornock, now 23, is believed to be the first former foster youth to petition the Tulalip Tribes in Washington for child welfare case files. The documents revealed troubling details of why the young Tribal member was removed from home. They also showed how, over 15 years, chances for family reunification and proximity to kin and culture were repeatedly challenged.

Under the watch of an Indigenous-run child welfare system, Thornock — who is Two Spirit and uses they/them pronouns — was moved through seven temporary foster care placements after being taken from their parents. The placements included brief stays with relatives, but they faced financial difficulty or circumstances that were too challenging to take on an additional child.

As a result, Thornock ended up with a non-Native, white Christian family off Tulalip lands. After Thornock became a teenager and timidly shared a new revelation about their identity, a legal guardianship was revoked — sending the high-schooler out into the world again, frightened and alone.

New insights added to the loss Thornock felt poring over these files in recent years. But they also contributed to a new vision for how life could take shape: supporting other foster youth and parents who’ve lost children. Seeking accountability through political advocacy. And working to interrupt generational patterns caused by colonization.

One thing was clear, above all else. They must speak out.

“What happened to me is not something I feel any other Tulalip youth, or any child, should have to go through,” Thornock said.

This Imprint series, Born of History, was reported over the past 10 months. It includes a four-day trip in March to the Tulalip reservation and dozens of in-depth conversations with Thornock by phone and videoconference. It also includes a review of thousands of pages of court files and interviews with multiple members of Tulalip Tribes, Thornock’s kin, attorneys, tribal officials, judges, social workers and academics.

Indigenous child welfare experts across the country who discussed Thornock’s journey said tribal foster youth leaving their communities is unfortunately all too common. But they also noted that Native American governments are making noteworthy improvements in their ability to maintain these vital connections.

“Forty years ago, placement off reservation in non-Indian homes was the norm,” said retired tribal and state court Judge William Thorne, who served on the trial and appellate bench for over 34 years in Utah, Idaho, Montana, New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, Wisconsin, South Dakota, Nevada, California, Nebraska, and Michigan. Child welfare leaders in tribal communities were “either county-trained and/or non-Indian,” he added in an email, with a focus on “‘rescuing’ children from the reservations and tribal life.”

Judge William Thorne — who has served in tribal courts across a dozen states in the U.S. — is a member of the Pomo and Coast Miwok Indian Tribes and is a leading expert on policies and programs that support Indigenous children and families. (Provided photo)

These days, Judge Thorne clarified: “We know better.”

“There are tribal programs that seek to support extended family as substitute caregivers. This goes beyond just asking if they are willing to take the children. It is instead saying: ‘What can we do to help enable you to care for these children?’”

Thorne and other Indigenous scholars also cited the inescapable impact of history — centuries of historical trauma and the federal government leaving tribes like Tulalip with inadequate resources to heal and protect children and families.

Thornock fully recognizes that.

“Our issues are rooted in colonial systemic oppression,” they said. But there’s another way. “Indigenizing child welfare just means recognizing that our culture is our elders, youth and children.”

Early days

Thornock’s child welfare case file, dated 2004 to 2019, helped unfurl the past. Oral history helped too. In search of cultural roots as a young adult, Thornock tracked down relatives and siblings who had been missing from their life, and could better explain what had happened.

Family members said Thornock’s mother, who is Tulalip, had her first child at age 13. She is now in recovery, but for decades she wrestled with drug addiction and maintaining her mental health. According to Tulalip Tribal Court records, Thornock’s father is “non-Indian.”

Older brother Brandon Cotton recalled the family’s early days. Cotton said their parents would lock themselves in a bedroom for days, getting high or coming down off drugs. Court documents show that social workers determined that the pair failed to safely parent.

For Cotton, 29, a single sound marks the morning Tulalip Tribes’ child welfare program — known as beda?chelh — arrived.

“I remember my mom death-screaming, I remember looking down the driveway to see beda?chelh with a sheriff’s escort, and just having no idea what’s going on,” Cotton said. “Deep down, you know, you just can’t put it all together.”

Beda?chelh takes over

The name beda?chelh is a Lushootseed word that means “our children.” It is pronounced “buh-DAH-chuh” and is also spelled bədaʔčəɬ, using the phonetic symbol “ʔ.”

“Our people are passionate about child welfare and beda?chelh because we treasure our children,” Tulalip Tribal Chair Teri Gobin said in a statement emailed to The Imprint. “We’ve always fought to preserve our tribe and families.”

Gobin described the tribal child welfare system — which cooperates with county and state agencies but maintains its own codes and policies — as the largest tribal program of its kind in Washington. She called the tribe’s children “our heart.”

Tulalip Tribes’ leaders would not discuss Thornock’s case, citing the confidentiality that is the core of their responsibility to Indigenous peoples. But they offered broad observations in response to a list of mostly unanswered questions.

Beda?chelh “focuses on what is best for the child, not what is best for adults,” Gobin said. She added that the tribe’s child welfare agency “is constantly evolving,” and includes voluntary services for struggling families to avoid further child maltreatment referrals. “The Tulalip Board of Directors and Tulalip leaders frequently evaluate all of our programs, including beda?chelh, to improve them for our people.”

In closing, the Tribal chair added, “We also know that we can always do better no matter how well we’re doing.”

***

The Tribe’s most recent publicly available figures show that in 2021, 135 Tulalip children and young adults were in foster care and extended foster care, serving youth ages 18 to 21. There were 20 beda?chelh staff positions. Four staffers were members of the Tribe, four were members of other tribes and 12 were listed as “non-Native” people.

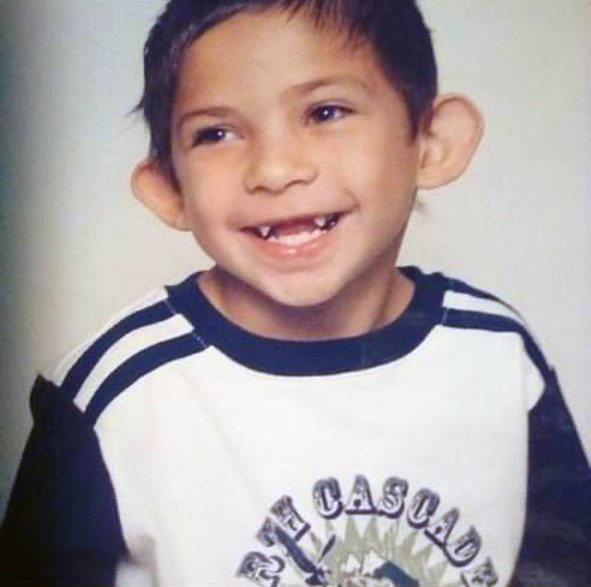

Thornock’s experiences in the early 2000s show how challenging it can be for tribal systems like these to keep children close to home, and how painful separation can be. Thornock was first removed from their parent’s home as a toddler in 2004. They recall being told to quickly gather their clothes and enter a white van, which drove off from the family’s front yard trailed by police.

Thornock implored a social worker to place them with their sibling, Cotton, who is roughly six years older. The siblings’ ties had already been strained by displacement: Cotton and another older sibling had been removed twice and later returned. And before Thornock was born, their mother lost custody of three older sons and a daughter.

In 2004, records show, the first placement was with a maternal second cousin. She later stated she could no longer care for Thornock because “she does not have adequate funds to take care of the Youth in addition to her own child.”

Due to her financial situation, the cousin was “planning to move soon and cannot take the Youth with her.” A caseworker noted at the time that Thornock was badly in need of dental care.

As Thornock moved through multiple temporary foster care placements, the relationship with their parents became increasingly jarring and confusing. Thornock was sent home to live with mom and dad for a short time in 2005, and then taken into foster care again, after the reunification attempt facilitated by the tribe was deemed unsuccessful.

Clearly, there were deep wounds the child welfare system was attempting to hastily patch up.

According to their case files and memories, Thornock’s parents failed to show up to many of the family visits beda?chelh arranged. A Tulalip Tribal Court order required them to be sober to visit with the kids, but the parents kept failing drug tests or refusing to take them. The missed family visits meant the siblings — scattered in different foster homes — lost the chance to connect with each other as well.

Still, for months in 2008, both parents wrote to the Tribe’s court repeatedly, trying to get their children back. The letters state: “We ask the court to allow supervised visitation” and “I know it’s in their best interest to see and visit with me.”

Years later, reading those letters tucked into the case files touched Thornock deeply. But eventually it seemed as if their mother had simply given up on recovery and on reuniting the family.

“We struggled as kids, seeing our mom so heavily impacted by us being taken away. She was slowly losing all her kids and it began to be too much for her,” Thornock said. “We were always in and out of the system, even before I was born. But our parents just ultimately decided they weren’t going to ever get better again — they weren’t going to even try.”

The Tulalip Tribes

Located on a 22,000-acre reservation about 430 miles north of Seattle, Tulalip Tribes participates in annual canoe journeys on the sea and waterways between Washington and British Columbia. Native people living along these shores once spoke 23 languages, including Lushootseed, Twana, Twulshootseed, Whuljootsee, S’Klallam and Saanich.

Today, Tulalip Tribes has more than 5,000 members. With two casinos, it is one of Snohomish County’s top employers. According to the Tribes’ website, the Quil Ceda Village is “a model for Native American economic development to sustain tribal community and culture” and represents the first and only IRS-recognized tribal city in the United States.

Prior to colonization, what is now known as the Tulalip Tribes once comprised Snohomish, Snoqualmie, Skykomish and other allied bands.

According to the Tribes’ historic account, these tribes spanned far greater swaths of land, from the Cascade Mountains to the islands of Puget Sound and as far north as Canada. Tulalip people sustained families with clams, mussels, spearfish, ducks, salmon, flounder and skate. Tulalip land provided a rich source of deer and elk meat, nettles, seaweed, wild carrots, onions and berries in abundance. Cedar was harvested for its wood, bark and branches — resources that, once plundered by white settlers, further endanger Indigenous children’s well-being.

The brutality of colonialism

In 1855, after the coerced signing of the Treaty of Point Elliott, the tribes who became the Tulalip peoples were ordered onto a reservation. Tribal leaders, who spoke a non-written language, signed the document with an “X.” The treaty left them with fishing, hunting and water rights so diminished they struggled to survive. Famine, disease and early death ensued.

Family separation was a common tool in the campaign of attempted destruction, and began quickly after the treaty was signed. A local Catholic mission school, later taken over by the federal government, aimed to sever Tulalip children from their culture. Between 1857 and 1932, thousands of Indigenous boys and girls were forced to attend the Tulalip Indian School. Thornock’s ancestors were among them.

The Tribe’s first female chair, an anthropologist and former chief judge, also survived the Tulalip boarding school. Before she passed on in 1991, Harriette Shelton Dover — born Hiahl-tsa in 1904 — described the conditions in interviews, an autobiography and a documentary film.

Being whipped by a school matron for speaking her Snohomish language was a shocking contrast to the culture she came from, Shelton Dover recounted. Before then, “slapping, pushing, beating or spanking never occurred,” she said, “and rarely were voices raised in Indian households.”

Les Parks, Thornock’s grandfather, said school staff were “trying to take our Indian away and forcing our people not to speak their language or suffer severe consequences.”

The impacts live on. Tulalip Tribal member Deborah Parker, now chief executive of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, told The Everett Herald her grandmother taught her to hide beneath the dining room table to avoid being snatched.

“I just remember those thoughts of, like, how scary would it be for government officials to come and try and take your child, and you have no choice?” Parker said. “I can’t imagine.”

‘Not created for us’

Beda?chelh was born of this history, said Kim Kealani Seven Renee Moser, Thornock’s aunt. She evoked colonization when describing her extended family’s struggles with child welfare systems. Due to the language barrier with Tulalip leaders, the Tribe’s treaty with the U.S. government ceded most of its land to white settlers. In its wake, Moser said, the beda?chelh program was modeled after state and federal laws.

“It was just not created for us,” she said. “We’ve always been there for our families. That’s the way it’s supposed to work — not this segregated, regulated, sideways, not-listening-to-anybody thing that it has become.”

Tulalip’s chair Gobin also described the brutal aftermath of colonization as integral to understanding the struggles of today.

“Healing the effects of generational trauma isn’t simple or easy, and we know it starts by repairing the harm caused when boarding schools separated our people from our children,” Gobin said. “That’s why, whenever possible, we keep children with their parents. If that’s not possible, we ask family members to step up. Regardless of where a child is placed, our goal is always reunification if it’s what is best for the child.”

In interviews with Tulalip News — syəcəb in Lushootseed — Tribal leaders describe a “desperate need” for respite care workers and tribal foster homes. (Tulalip News is owned by the Tribe and operated by Tribal members, but published articles do not necessarily reflect the opinions and views of the Tribe itself or its leadership, staff said.)

The article states that compensation is available “for respite care workers and/or placement homes” once services are in place and a home study and background check have been completed, with grant amounts that “vary applicant to applicant.”

But there are other issues to contend with.

“Unfortunately, with very few tribal volunteers, many of the cases are forced to lean on state-sourced foster resources and non-tribal homes,” Tulalip News reported. That leaves “a lot of questions and concerns about where these children will end up, and how they will remain connected to the tribe and their culture.”

Delia Williams, a former foster youth and a beda?chelh placement specialist, told the weekly newspaper that “Our whole goal is to try and keep our kids here with us.” But she added that when Tribal families are asked to volunteer, they often express distrust of social workers, fear the impact on other children in the home, or simply lack the resources to feed and care for another child. “It’s sad because 97% to 98% of the time, these family members will say no. They either aren’t willing or aren’t able to take their family in,” Williams said.

As a result, “a tribal child could end up living anywhere within the state of Washington, and could be hundreds of miles away from their people,” the article states.

That’s what happened to Thornock. But as that move happened, Tulalip Tribes — unlike what county and state governments might have done — did not cut legal ties with their parents.

Keeping parental ties

Under the federal Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997, which is followed in state court systems, when a child has been in foster care for 15 of 22 consecutive months, child welfare agencies are required to pursue a termination of parental rights. Parents who do not meet strict timelines to reunify with their children — by attending court hearings, becoming sober or agreeing to drug testing — can meet this fate. Termination of parental rights means legal ties are severed for life, a court action referred to by some in the child welfare field as the “civil death penalty.”

Tulalip Tribes took a different course. Although Thornock’s child welfare case continued on and off over 15 years, beda?chelh never sought to formally sever ties with the foster youth’s parents.

“There are compelling statutory, cultural, tribal and historical reasons to recommend against termination of parental rights and adoption in this case,” records from 2005 state. Citing Tribal codes, beda?chelh officials clarified “it is the stated policy of the Tulalip Tribes to protect the best interests of Tulalip youth by maintaining the connection of Tulalip youth to their families, the tribe, and the tribal community.”

Tribal leaders outlined stakes that reached far beyond one individual family, noting: “Termination of parental rights and adoption would greatly jeopardize this connection, as well as the future of Tulalip Tribes.” Such a move, the records state, “is contrary to the Tulalip Tribes’ history, culture, and beliefs.”

Experts in Indigenous child welfare practices who spoke to The Imprint for this series agreed that Tulalip is among the majority of tribes steadily moving away from the practice of terminating parental rights. The trend represents a stark contrast to the way foster care cases proceed in non-tribal courts nationwide. But the need for reform is great, they added.

Reflecting a nationwide trend, in 2021, Washington’s Indigenous children were three times as likely as white children to enter foster care, state data show.

Reclaiming culture with kin

In Indigenous communities, relatives are vital to retaining language, spiritual practices and customs passed down through the generations. But foster care and adoption disrupt that continuity.

Moser, a Tulalip tribal member with four children who works as a tattoo artist, played a fleeting but critical role in the lives of Thornock’s sibling group. From 2003 to 2004 she fostered two of their sisters under an emergency court order, and provided her nephew with emotional support and transportation to appointments and family visits. Moser’s home became a special place for the siblings to gather.

At the time, Moser, now 42, was immersed in Tulalip cultural reclamation for herself and her children because she too had grown up off Tribal land. Seated at her kitchen table with her small nieces and nephews, Moser helped them with their Lushootseed lessons. Together, they made deerskin drums and wove baskets with strips of cedar.

“I was trying to learn with them so I could help them claim their own culture, because I felt that was a big hole in my life for a long time,” Moser said. “I didn’t want that for these kids.”

From her own childhood, Moser knew the vital importance of extended family willing to step up. “So when all of the kids came around, I told myself that I don’t care if I have to pull up six extra cots and make fry bread 24/7,” she said. “We’re going to do this thing.”

Thornock had been taken from home, but in these preschool years, members of Tulalip Tribes remained nearby. There was comfort in that.

So why didn’t it last?

In part two of this series, coming tomorrow, Andres “Dre” Thornock leaves tribal land.