Here is some of my family story and our small connection to the Manhattan Project. I am sharing this based on my observations, my memories, interviews with family members, stories I have heard and some serendipitous research my daughter did for a high school project that had surprising results.

New Mexico has always been a somewhat isolated place. Sure, Santa Fe is trendy now, but one reason northern New Mexico developed such a rich and unique culture is because the area was historically far from the centers of power. It was remote, often disconnected, and a place people would travel to live differently.

When the government was looking for a place for the Manhattan Project, that remote, disconnected quality caught the attention of General Leslie Groves and Julius Robert Oppenheimer. They knew the remote mesas and canyons were a place they could build a secret town — one that Oppenheimer described as a location having “soul-enhancing beauty” that could draw and inspire brilliant minds.

One of those drawn to the good-paying jobs in the secret mountain city of Los Alamos was my great-grandfather, Jake Seligman. He was a humble, thoughtful and by all accounts generous and sweet man. He loved to laugh and never talked politics. He hand-built the house I was raised in from adobe mud brick. His grandchildren, wife and daughter admired him. He was meticulous, could fix anything and in the 1940s was ahead of his time in his profession.

Jake Seligman was an electrician and was the guy his friends would call to help wire their houses. The house I was raised in near the Santa Fe Plaza has more electrical outlets than most houses from that era. And the 1940s-era electrical wiring and panel in that house has served perfectly over the years — even as microwaves, clothes dryers and other appliances were invented.

My mom says that my first complete sentence was said to him as he worked to rewire a light fixture over my crib. Those words, according to my mom: “I see Pompo up there.”

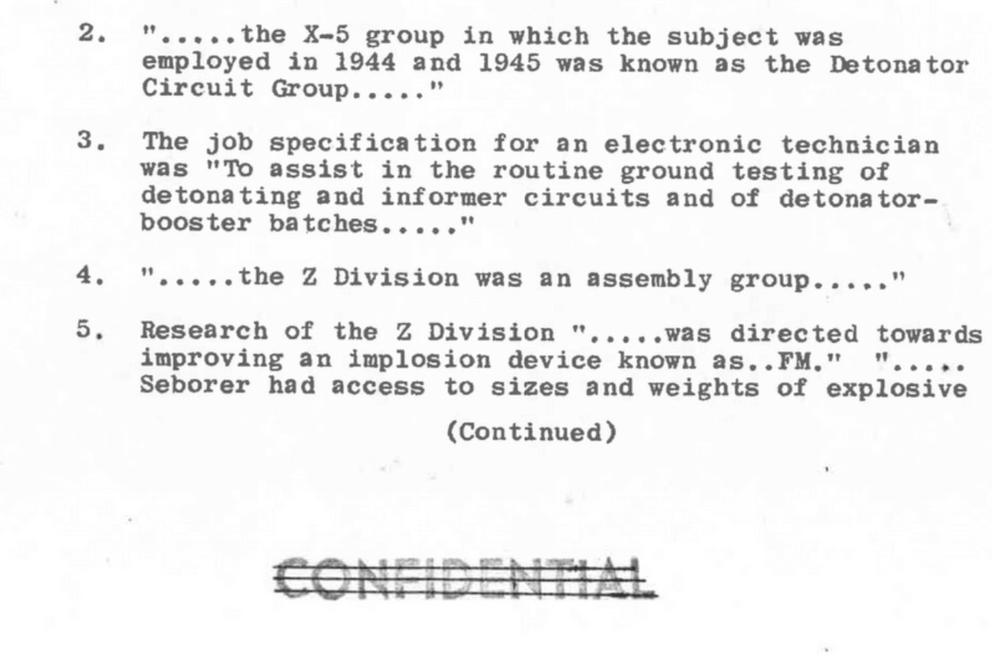

Grandpa Jake, as we all still know him in our family, was part of the “X group” — a division of the Manhattan Project. According to now-unclassified documents, X group was responsible for detonator development. The team he supported was responsible for the design and the complex wiring that connected the explosives surrounding the ball of plutonium. He was one of the original 1,400 lab workers assigned the task of developing the world’s first atomic weapon.

It was certainly a complicated time. He and many of his co-workers likely did not completely know what they were working to build. Many, like Grandpa Jake, were drawn into the effort because of their refined skills and the promises of good jobs.

I am told he never talked about his involvement in the war or the Manhattan Project. It wasn’t exactly the kind of topic G.I.’s and civilians wanted to discuss around the dinner table. It was a terrible time. We knew he worked there, but it wasn’t until my daughter did some research for a school project that his name came up in some previously classified documents we found.

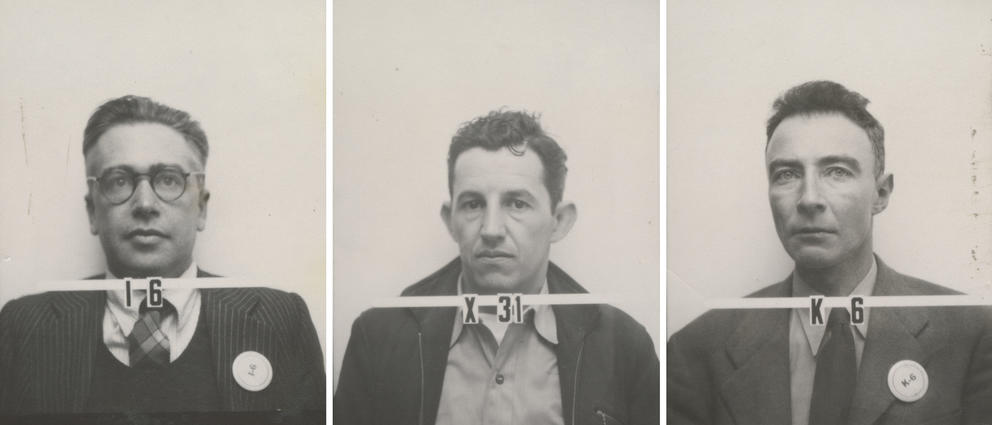

We found restored security badge photos in the Atomic Heritage Foundation archive. The letter on the staff photos identified what group a member was part of. The number was a unique identifier. The Manhattan Project was an effort for which secrecy and security were top priorities — secrets that really never left the remote mesa up on the hill.

His name also surfaced in alphabetical order, near Emilio Segrè, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist, in now-unclassified logs and a phone book for the original facility.

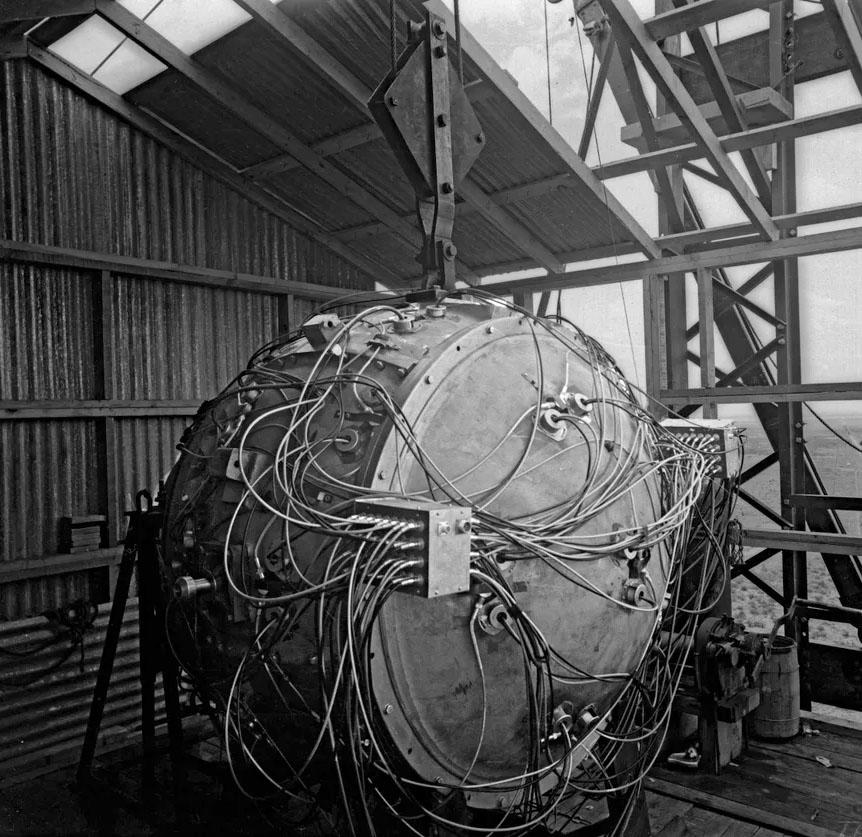

The test at Trinity Site required hundreds of miles of wiring, and X group was responsible for all the connections that wired “the gadget” to the explosives that compressed the ball of plutonium. From the research I have done, it seems he was on site early on the morning of July 16, 1945 in the Jornada del Muerto when human history changed. An anecdote from his funeral in 1976 supports this — a friend shared a story about him being present at Trinity Site for the test.

Also, I have a distinct memory as a small child in Santa Fe: There was a brass tube with caps on both ends tucked away on the top shelf of a closet in his house, where I was raised after he passed away. If the thick ends were unscrewed from the tube, you could see weird green mineral-looking stuff inside. I distinctly remember trying to figure out what it was and putting the stuff in my hand. Others in my family now say that was likely trinitite, the material left after the Trinity explosion superheated the New Mexico desert to hundreds of thousands of degrees. The tube still sits in a closet at my grandma’s house – the contents long lost.

The film Oppenheimer will certainly open old wounds. It was a terribly complicated time. In recent years my family has visited the sites of Japanese internment camps with some of our best friends. Our friends’ parents were ordered to relocate from Seattle to the camps in the 1940s. Those parents also never talked about their experience. With our kids, together we have pursued stories and research to better understand that time and our family’s place in that history.

Get daily news in your inbox

This newsletter curates some of the most important headlines of the day from Crosscut and other news outlets.