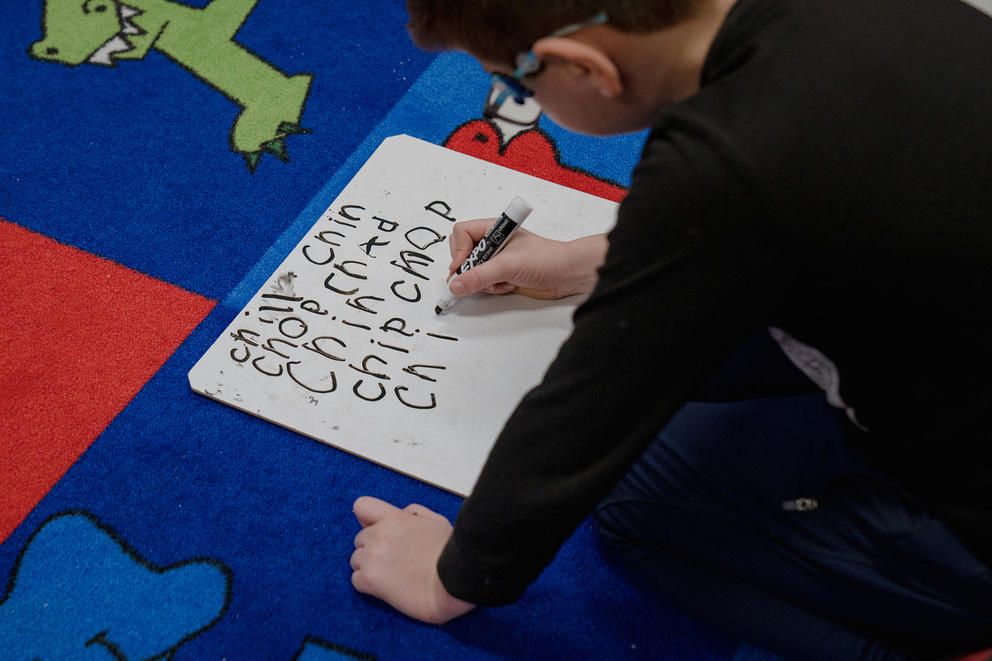

In one first-grade classroom, all the students are learning the same phonics lesson, but some work with a teacher at a large touch-screen while others huddle over worksheets, and still others are doing a lesson tablet in hand with headphones on.

At recess, numerous large signs are posted throughout the play area, with a grid of pictures of kid-relevant concepts such as “swing,” “no,” “play,” “teacher” and “nurse,” along with frowning faces and smiling faces. Students also have access to cards that they can wear on lanyards so they can communicate with one another while playing, whether a student can speak vocally or not.

The students were inspired by the signs to ask for the portable communication aides, said Cathi Davis, Ruby Bridges principal.

“Let’s support the fact that all our students are learning about communication.”

Ruby Bridges Elementary is one of several dozen Washington schools that have centered inclusive practices and been part of a concerted statewide push to increase the percentage of students who spend more than 80% of their time with their grade-level peers.

The goal of decreasing the amount of time students with disability accommodations spend outside their classrooms working with therapists and specialists was one topic of debate during last fall’s Seattle teachers’ strike; the concept has been part of a bigger special-education policy debate – and a focus in many other places – for years. In Seattle, teachers expressed concerns that this change in classroom structure would not be supported by the staff necessary to make inclusive learning both possible and successful.

In the past 40 years, a growing number of students across the United States who need special education or disability accommodations have been meeting this 80% threshold. In 2020, 66% of these students nationwide met that general-education instruction time goal, an increase from 31% in 1989, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

But Washington has lagged behind this national trend, with about 60% of students with special education or disability accommodation needs meeting that criterion. In 2019, the state was ranked 44th out of 50 in inclusionary practices, according to the state’s own figures.

“The whole thing about inclusion is that every student has a right to grade-level content,” said Mary Waldron, director of inclusionary practices at Puget Sound Educational Service District, one of the nine regional education agencies in Washington that coordinates multidistrict programs and initiatives. “So even if a student needs additional support, they're not missing their core math instruction to get additional support ... That's what we're trying to avoid.”

Waldon and others are part of the statewide push to increase inclusionary practices at K-12 schools. This effort includes the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction and the University of Washington School of Education, which is working with dozens of schools and classrooms throughout the state that are adopting more inclusive practices.

In 2019, OSPI earmarked $25 million in the 2019-2021 biennium and $12 million in the 2021-2023 biennium for professional development to train teachers and administrators to adopt more inclusive practices in their school systems. This year, the state agency is asking the state Legislature for $5 million a year to continue with this training.

The training is important, supporters say. Knowing how to restructure a lesson plan with universal design – so it can accommodate all students and their multiple learning needs – as well as formulate Individual Education Plans for students with disabilities or who need special education can be a daunting barrier for some teachers and administrators.

“It’s a big learning curve for a lot of people, like, ‘How do I do this?’” said RinaMarie Leon-Guerrero, an education specialist at the UW Haring Center, which has been researching special education for more than 50 years.

The Haring Center has been working with dozens of schools throughout Washington at various levels of developing more inclusive practices, Leon-Guerrero said. Districts and schools involved in the development program are scattered throughout the state, including Northshore, Highline, Spokane, North Thurston, Kittitas and Bellingham. This often requires system-wide change, including rethinking schedules and how schools use their existing resources, she said.

For example, specialists continue to work to accommodate Ruby Bridges students, whether assisting in the classroom or stepping out momentarily to do one-on-one work, but those work times are folded around the students’ main lessons rather than at a set time every week.

“But it might be that they're not missing [their classrooms] during core instruction time, or … that services are coming to them,” Leon-Guerrero said. “That needs flex spaces and not them moving to meet adult schedules.”

Ruby Bridges also has resource rooms where instructional assistants and special-education teachers can step aside with one or more students during a lesson to help them navigate specific needs. That assistance can range from reviewing a new concept to supervised physical activities that could help a student regain focus.

“The biggest difference between traditional classrooms and inclusive classrooms is that traditional classrooms are very reactive. So we kind of wait for students to struggle before we then provide them additional support. Inclusive classrooms are really built on the assumption that learner variability exists,” she said.

For example, a science teacher who knows that their class has students with varying levels of reading skill would create lessons with that in mind.

“I can proactively plan for other ways to make that information accessible. Maybe I can provide a video, maybe I can provide an audiobook version of the text or my district test software that will read the text aloud to a student,” Waldron said. “I'm not waiting for the student to show me on a test that they don't understand the concept. I'm being proactive in my approach to making sure that students can access [it].”

These practices help students at all levels, Waldron argued. While the percentage of students who qualify for education accommodations has remained pretty stable over the past decade, the most recent measurement scores for grade-level reading and math show that many students might need additional academic support after returning from remote and disrupted learning.

“You can't deny that students came back into school full-time with a wide range of learning needs that they did not have before the pandemic, and that the number of students who needed additional support grew from before the pandemic,” Waldron said.

Educators who are pushing for the changes say that inclusive education not only benefits the students needing extra help, but also helps their classmates develop a greater sense of empathy and ability to relate to and be more inclusive of people of varying abilities.

“What does it tell a kindergartener when the bell rings, and they go straight into a classroom, and their classmate turns left?” said Davis, the principal at Ruby Bridges.

For all its subtle differences, the school was opened by the Northshore School District in 2020 as a traditional neighborhood school to accommodate the growing elementary-school population north of Bothell and Woodinville. The school, named after the civil rights activist who as a 6-year-old became a national face of American school integration, also emphasizes celebrating the ethnic and cultural diversity of its student population, which is more than 60% nonwhite.

And while Ruby Bridges Elementary was intended to be a neighborhood school and not a magnet, the school has a slightly higher percentage of students with disabilities than other Northshore elementary schools and than the district as a whole. This could indicate that families of students with disabilities are transferring their children there in the hopes of a more inclusive learning experience.

Supporters of increasing inclusive practices in schools hope that in the future, such differentiation won’t be necessary.

“The schools and the districts that I work with either have or are moving towards a belief system that really values that learner variability in that student diversity, and are really seeking to meet the needs of all of their students in the best way that they can,” Waldron said.

Correction: This article was corrected on Jan. 19, 2023. An earlier version of this story misstated which communication aide that Ruby Bridges students requested. The story was also revised to clarify that UW Haring Center is working with the schools and classrooms in partnership to develop inclusive practices.

Get daily news in your inbox

This newsletter curates some of the most important headlines of the day from Crosscut and other news outlets.