In the past 20 years, schools have been transformed in an effort to boost student safety against the possibility of school shootings, including the increasing percentage of high schools with armed officers on campus, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Other school “hardening” efforts nationwide have included locking entrances and exits and installing gates and metal detectors.

But some people are also taking a closer look at the mental toll on students and teachers from having to think about active shooters. The Washington State Legislature passed a bill this past year that now prohibits live simulations or reenactments of active shooter scenarios during lockdown drills.

Bill sponsor Rep. Amy Walen, D-Kirkland, told the House education committee the bill was meant to address drills that vividly mimicked an active shooter situation, including asking students to create barricades and block classroom doors.

“In the name of safety … the practice [of active shooter simulations] was creating more trauma than creating the behavioral modification that we want to see,” said Rep. Sharon Tomiko Santos, D-Seattle, chair of the House Education committee said last week. “School safety is as much about the social-emotional health of our students, and in our state policies we unwittingly contributed to some of that trauma. And we’re more sensitive now that we have gone through COVID.”

Lockdown drills will still happen, along with drills for sheltering in place and evacuations for fires, earthquakes and other emergency situations, she said, but lockdown drills must be grade-level appropriate and not include reenactments of shootings.

The vast majority of students will not have to face a shooting at their schools, but more than 95% of schools nationwide have lockdown drills. Walen and other bill supporters cited research from Georgia Institute of Technology that was published last year showing evidence that drills reenacting a shooting situation can traumatize students for three months afterward. The research was based on social media analysis and suggested that schools find less trauma-inducing methods to acheive preparedness.

Despite the efforts across the country to protect schools, the losses are still high. According to a tracker by Education Week, 83 students, teachers and others have been injured or killed in shootings on K-12 campuses nationwide this school year, including a shooting at Yakima High School in March in which a 15-year-old is accused of shooting another 15-year-old, who died, and an 18-year-old, who survived.

Santos said that the change regarding drills complements the state’s overhaul of school safety measures that state lawmakers passed in 2019.

That 2019 bill, SHB 1216, covered multiple types of emergencies, including lahars, tsunamis and fires. It codified policies for school district coordination with local emergency responders, the creation of programs to assess threats at school and training for school resource officers — a commissioned police officer stationed at a campus — on dealing with students.

Paul Kramer, the citizen sponsor of an initiative that increased restrictions on the purchase and ownership of firearms, speaks about efforts in Washington state to reduce gun violence on Feb. 14, 2019, in Seattle. The man who shot and killed four people at a Tulsa, Oklahoma, hospital bought his AR-style semiautomatic rifle just hours before he began the killing spree. That would not have been possible in Washington and some other states that have waiting periods of days or even more than a week before a person can take possession of such weapons. (Ted S. Warren/AP)

Santos said that for all that Washington state has done to try to fortify schools and limit guns in certain public spaces, the next major moves on safety need to come at a federal level, though the populace has become polarized on the issue.

“There is an increasing divide in Americans’ ability to have a common ground around policy with respect to guns and the place of guns in society,” she said.

For Olympia High School freshman Sarah Walz, the possibility of a shooting like the one that recently took the lives of 19 students and two teachers in Uvalde, Texas, has always been part of their school experience.

Walz, 14, said that in kindergarten their school went into lockdown because a man outside the school was carrying what turned out to be an umbrella.

“I remember being in a dark classroom, on the floor, not knowing what would happen,” Walz said. “That was a powerful moment to me, it was a disheartening thing.”

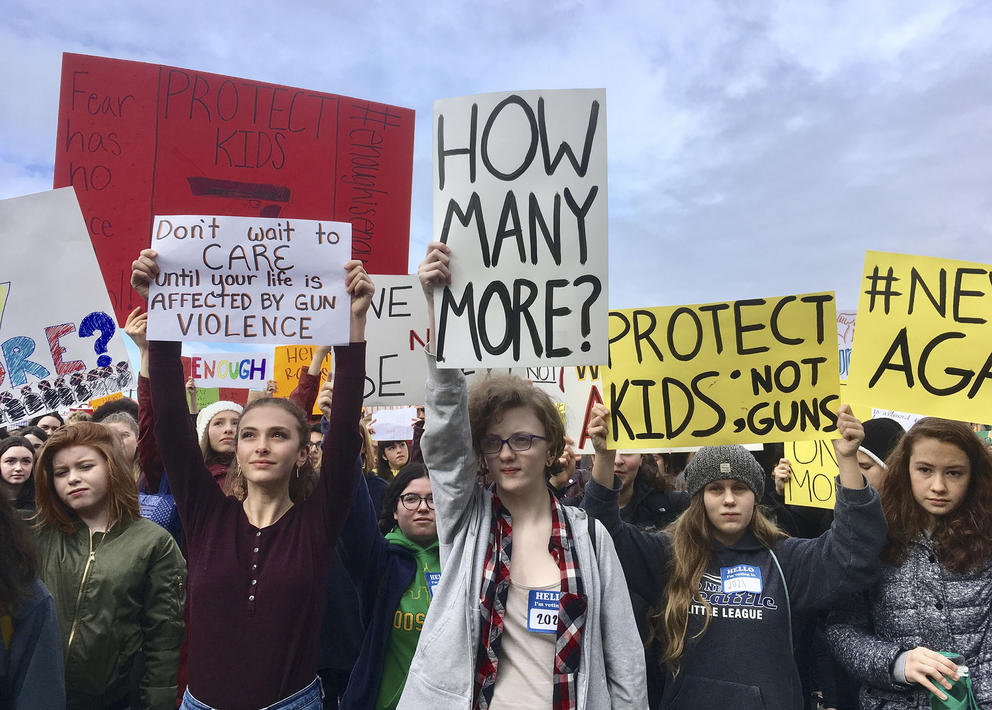

Walz joined hundreds of demonstrators at the recent March for Our Lives in Olympia, which came together after an 18-year-old entered Robb Elementary School in Texas and killed third and fourth graders and two teachers in May.

At the march, first established in 2018 after the shooting at Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, demonstrators called for added gun control as a way to increase safety at schools and other public places.

Walz’s classmate, Nell McGuigan, 15, who also attended the march, said many students felt a sense of shock and sadness after the Uvalde shooting because the shooter attacked an elementary school.

“It’s having students go to grownups and say … ‘We are here to tell people that we don’t want to get shot,’ ” McGuigan said.

McKaughan, the Tumwater teacher, said that the federal government should examine the insurance and marketing of guns as a possible means of increasing safety. He also attended this year's March for Our Lives.

“I’m not against guns, I just think they need to be well-regulated according to the Constitution,” he said. “I feel like I’ve been living in this ‘violent world of education’ my whole career. I’ve just come to expect it and I don’t want it to be that way.”

Walz and McGuigan, the Olympia ninth graders, said schools should also do more to address mental health issues and help all students feel seen as a way to improve school safety. They both said the lockdown drills are ingrained in their school experiences.

“I think drills definitely make you think of the different possibilities that arise,” Walz said.

“Along that same line, it helps you prepare. But you shouldn't have to,” McGuigan said.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misspelled Nell McGuigan's name. This has been corrected.