In Central Washington, there are few places where trans, queer and gender nonconforming youth can find that sort of welcome. Aside from The Space, the only other LGBTQ center for youth in the region is the newly open Helen House in Ellensburg.

Babcock, originally from Grandview, a small town halfway between Yakima and the Tri-Cities, grew up in a religious household. As they began exploring their true gender identity, The Space offered a place to simply sit and talk with other young queer people, watch movies, play games and be accepted for who they were.

“It was a place where I immediately walked in and knew: I'm OK,” said Babcock, who’s now 25 and serves as a volunteer at The Space. “I still needed to figure things out. But here it doesn't matter, you still belong here.”

It’s a difficult time to be an LGBTQ youth in rural America, and the Northwest is no exception. In March, the Idaho House passed a bill that would make it illegal to provide gender-affirming care to transgender children (though Idaho’s Senate later voted down the bill).

A nationwide movement to limit discussion of sexual orientation and gender identity among children is growing, whether it’s Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” act or efforts to ban the graphic memoir Gender Queer in school districts across the country, including those in Kennewick and Walla Walla (Walla Walla voted to reject banning the book, and Kennewick did not take any action).

In Ellensburg, a recent student election for class president at Ellensburg High School was marred by online harassment and vandalism in response to one candidate being openly gay.

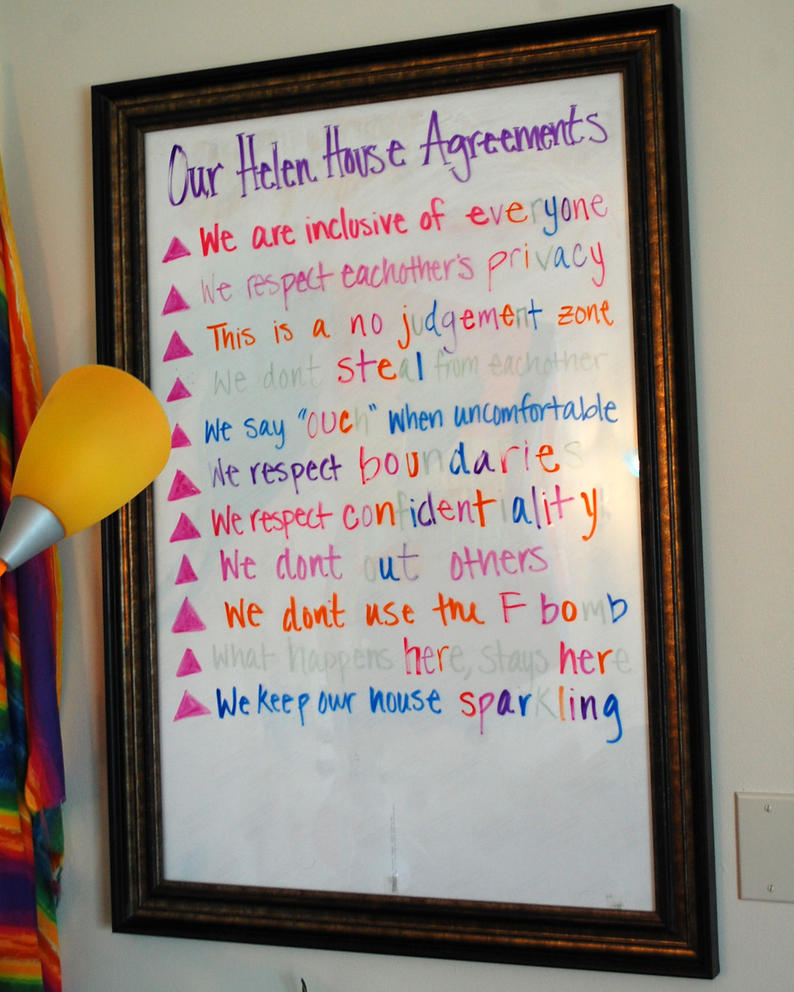

Tylene Carnell, a longtime LGBTQ activist and the founder of Helen House, noted that attitudes in Ellensburg toward trans and queer people are mixed. She has found plenty of local volunteers and donors to support a space for LGBTQ youth, especially among students at Central Washington University. Although Helen House formally opened in 2020, it has had a bumpy start in part because the center had to shut down during the pandemic.

Carnell, who is originally from Boise and moved to Ellensburg in 2001 shortly after transitioning, said the university provides a more progressive, welcoming environment, but life as a trans person is still a challenge there.

“Being trans here is a lot closer to being trans in Seattle than it is being trans in Idaho,” Carnell said. “But there are times that I’ve been questioned coming out of the bathroom. Or times I’ve left downtown and went home to go to the bathroom because I was uncomfortable.”

Anna McGree, director of The Space, said only about a quarter of the youth who regularly visit the Yakima center have active support from their families. Most of the others either haven’t told their families or visit despite a lack of encouragement.

“No matter where you go, there are some people that just aren't going to accept a place like this,” McGree said. “We really try to focus on the people that do love this place and want to see it succeed.” She noted that the center doesn’t make its address public and doesn’t display emblems such as pride flags — out of an abundance of caution.

Founded in 2016 and operated by Yakima Neighborhood Health Services, The Space offers a refuge that includes social events, peer activities, mentoring and mental health counseling. There’s a cozy common area with a TV, a well-stocked art room, a selection of clothing and costumes and a small kitchen. McGree said her staff and volunteers also work closely with Rod’s House, a drop-in center for homeless teens, to provide services to LGBTQ youth facing housing insecurity.

Of the 10 to 15 youth who regularly visit The Space, McGree said, five are currently housing unstable. “A lot of them are couch surfing and never have a stable place, even if they’re not out on the street,” McGree said. A staff case manager offers assistance to those who mention they’re homeless, setting them up with social services, mental health counseling and health care. They often take advantage of the center’s shower and kitchen, which is stocked with snacks.

Julie Bautista, a youth outreach coordinator with The Space, helps these homeless youth find housing services and provides help with practical skills such as applying for jobs or writing a resume. “A lot of them don’t have job experience or references,” Bautista said. “So I try to make it look as professional as possible without it looking like a blank piece of paper.”

Baltista, who identifies as nonbinary, first heard about The Space when they were leading the Gay Straight Alliance in high school. Though they describe Yakima as “divided” and having moments of “drama” regarding the trans and queer community, they are very happy living in the city, which now boasts regular drag performances and an annual Pride parade.

“I personally think it's a wonderful town,” Baltista said. “There's definitely people that disagree. But I absolutely love it. I love the community here.”

The pandemic was hard on the center and the young people who depended on it, McGree said. But programs such as The Space’s mentoring program — in which LGBTQ young adults regularly talk with trans and queer youth — continued during the COVID-19 pandemic via video calls. Although the center still isn’t up to pre-pandemic numbers of youth served, it’s gradually rebuilding.

The Space is especially useful to trans youth who are questioning their gender identity. In addition to providing access to items like compression chest binders, the center can refer young people to Yakima Neighborhood Health Services to receive gender-affirming medical care.

“Our medical staff is very accepting,” McGree said. “They’re great, though a lot of people go to Seattle for their transition. And that can be a barrier in itself because not everyone has the means of transportation to get there.”

According to University of Washington researcher Arin Collin, who co-wrote a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in February, providing adolescents access to gender-affirming medical care such as hormones and puberty blockers is associated with a 60% lower chance of depression and 73% lower odds of suicidality, Collin said of the 100 youth surveyed. “Also, for the folks who did not receive this care, the severity of the depression itself was much worse.”

Community support, like the kind youth find at The Space, is also extremely important, Collin said. “There's a very robust body of research, including work by Kristina Olson, speaking to the efficacy of social transition. When youth are supported in their transition from a social perspective — allowing for preferred gender, use of a name consistent with their gender identity — they have parity with their peers with regards to mental health outcomes.”

McGree agreed, noting that having in-person gathering time has made a huge difference in young people’s mental well-being. She pointed to one visitor who had been hesitant to talk with others or share anything about their gender identity.

“Then they slowly started letting their guard down,” McGree said, adding that they signed up for the mentor program soon after. “It was really cool to see that progression from ‘I'm not talking to you. I don't want to talk about identity. That's not something that we talk about in my house’ to ‘I want to open up, show you who I am.’ ”

The Space also holds regular outings, whether it’s giving the youth gift cards and taking them shopping during the holidays, or a recent trip to see a local production of Hairspray. “It was so fun,” McGree said. “Many of the youth had never been to a big play like that.”

Though none of the youth currently in the program wanted to talk publicly about their experiences for this article, in a video The Space created to promote its programs a trans teen talked about being threatened at school, and how stepping inside the doors of The Space offered a haven. “I was in a really bad place,” they said, “but that was like a moment of pure love.”

Babcock noted that just the act of asking for pronouns and affirming nonconforming genders can make a huge difference. During an outing to a coffee shop not long ago, one of the youths ran into the group while they were with their parent. They quickly whispered to their friends to use different pronouns, since they weren't out at home.

“That is really detrimental to someone's mental health,” Babcock said. “And this is a place where they can be themselves. And they may really want to come out to their parents as who they are. But for whatever reason, that's not safe.”

When asked if there was a particular success story they’d observed working at The Space, Baltista laughed and said, “All of them, 100%. Every time you see someone new come in, you can see it on their face. They feel so happy, so comfortable talking to LGBT people just like themselves. They feel safe, cared for. And sometimes they don't want to go home — this is a home away from home for them.”

This version of the story corrects the spelling of Youth outreach coordinator Julie Bautista's last name.