“When the social worker first came in, and I tell her, ‘I have an attorney,’ their whole demeanor changed,” Justice, now 38, recalled. “I felt protected. I felt like I had arms around me and my child.”

Justice’s attorney at the time was Adam Ballout, a public defender frustrated with how many newborns the state wrenches from addicted moms, instead of providing them with the help they need to stay together. Ballout is a co-founder of the nonprofit FIRST Clinic in Snohomish County, a program dedicated to preventing trauma caused by family separation. The model pairs free legal counsel with support from a parent ally and health care professionals — and, ideally, reaches pregnant women with substance use disorders before they give birth and CPS sweeps in for a removal.

So when Mason was born in the spring of 2020, Justice had a chance. And her legal team had plenty to work with.

This story is being co-published with The Imprint, a nonprofit news outlet focused on the nation’s child welfare and youth justice systems.

Justice had remained clean since she had started drug treatment a month and a half before giving birth. And even though she knew the hospital would report her prenatal drug use to child welfare authorities, the FIRST Clinic had helped put a plan in motion to persuade them not to take her newborn into foster care. They had arranged for a hotel stay until permanent housing came through. Justice was taking the anti-addiction medication buprenorphine and getting assistance from community groups and a parent ally.

With the support from the FIRST Clinic, which stands for Family Intervention Response to Stop Trauma, the meeting with CPS at Providence Regional Medical Center in Everett “was a lot different than the first time,” Justice said.

Legal clinic is a rarity

The FIRST Clinic’s three family lawyers and one parent ally provide a rare combination of legal advocacy and practical and moral support. Employees say the team has successfully prevented hundreds of infant removals in Washington since 2019. The program launched as a pro bono branch of the Everett-based ABC Law Group, and last year received its first public funding: $250,000 from the state Legislature to be used over two years.

Referrals come from drug treatment centers, doctors and even the Washington Department of Children, Youth and Families, which oversees the state’s child welfare system. About half of the clients have yet to give birth, but they are likely candidates to be reported to CPS or have histories with the agency. In other cases, the team rushes to the bedside of postpartum women, sometimes arriving when a social worker is already at the hospital.

Nancy Gutierrez, a spokesperson with the Department of Children, Youth and Families, said in an email that her agency has worked to “shift practice and critically think about decisions around court involvement and removal of any child, not just substance-exposed children prior to FIRST Clinic’s implementation.” That work has included “safety planning to make every effort to keep children in the care of their parents and avoid out-of-home placements.”

The department described its contract with FIRST Clinic as “a complementary support” to those efforts.

While the FIRST Clinic is unique in Washington, other states have similar models. The nonprofit Legal Services of New Jersey, for example, has built a robust pre-petition legal representation program with four attorneys, two social workers and two parent allies.

Jeyanthi Rajaraman, who led the New Jersey program from 2018 until early this year, said all of the roughly 300 families served during her tenure had avoided family separation.

“It’s not shocking that these cases are successful,” said Rajaraman, who is now helping advance such prevention-focused approaches across the country as a consultant with Public Knowledge’s Family Integrity & Justice Works. Housing and other poverty-related issues underlie many child welfare cases alleging neglect, she said. Resolving those issues is “not as difficult as everyone expects it to be, and it’s really what’s truly in the best interest of the child.”

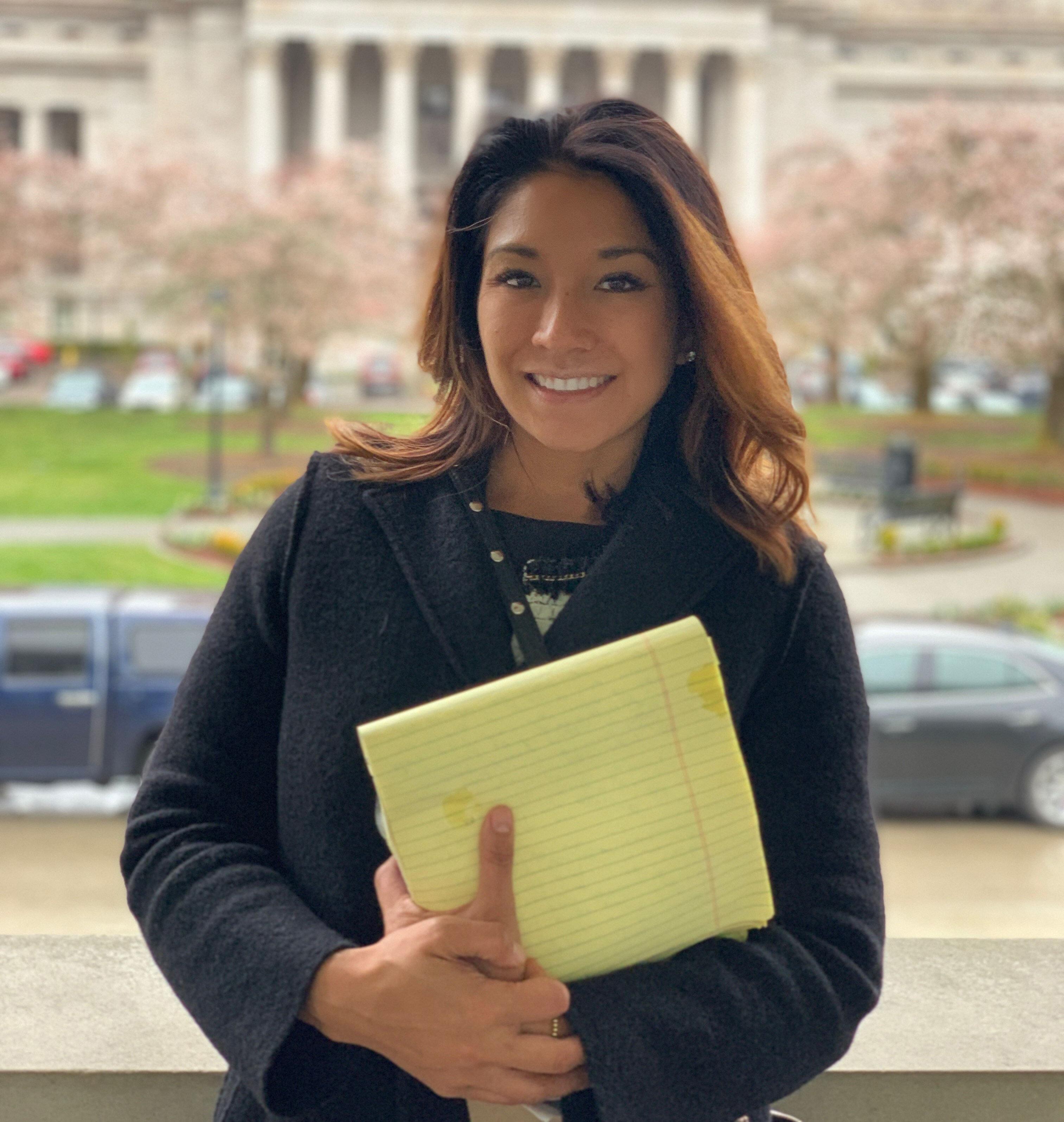

Interest in pre-petition legal representation has exploded in the past year, said the FIRST Clinic Executive Director Taila AyAy. Membership in an informal network run out of the University of Michigan Law School for those interested in the work has grown each month.

“I’m hopeful that this is something that will spread and will be available to everybody,” AyAy said.

Moms and babies need each other

The importance of maternal-infant bonding is well-documented.

“Mothers and babies have a physiologic need to be together during the moments, hours, and days following birth, and this time together significantly improves maternal and newborn outcomes,” said an article published in the Journal of Perinatal Education.

Babies born dependent on opioids, in particular, benefit from those bonds. Research has shown infants are able to leave the hospital much sooner when they remain close to their mothers, rather than being taken to the neonatal intensive care unit and slowly weaned off of opioids. The model, known as “eat, sleep, console,” is becoming the standard of care around the country.

Nonetheless, parental drug abuse remains a leading factor in child removals. Nationwide in 2020, substance use was at least one factor in 35% of removals, affecting nearly 76,000 children of all ages, according to federal data. That’s up from 26% in 2010. Child welfare experts say the official numbers represent a low estimate. In Washington, 79% of newborns, a total of 585 babies, were removed in 2020 because of parents’ substance use, according to the state child welfare agency.

Chelsie Porter, a doula who began referring patients to the FIRST Clinic last year, has noticed a big difference in the tenor of meetings with CPS when the program’s lawyers are present. “Many times, if legal representation like the FIRST Clinic isn’t there, it feels like CPS has decided what it’s going to do before the meeting happens,” she said. In contrast, when the FIRST Clinic is there, “it’s a more thoughtful meeting. It’s a meeting that feels a lot less predetermined.”

Porter is a founder of the Harm Reduction Doula Collective, which works with pregnant and parenting people who use substances. The legal clinic, she said, is “a huge game changer, and particularly for families that get involved earlier in pregnancy.”

Porter recounted the story of one such couple. When their baby was admitted to the hospital for a medical condition, social workers accused the baby’s parents of neglect and threatened removal. “Without FIRST Clinic being involved, I can promise you that they would have had their child removed from them,” Porter said.

‘Shell-shocked, broken people’

Without the help of a program like the FIRST Clinic, parents who qualify for a court-appointed attorney don’t receive legal representation until the first dependency court hearing, which doesn’t take place until three days after children have been removed. At that point, the state can argue that children need to remain in foster care or be sent to live with relatives.

Except in rare circumstances where parents can demonstrate an extraordinary level of support, those hearings typically end with a judge ordering out-of-home placement, FIRST Clinic’s AyAy said. By then, it can be too late to reverse the damage.

“You would see these shell-shocked, broken people that had already given up before really it had even begun,” said AyAy, an attorney who has represented parents in dependency cases for 13 years.

“It seemed to me such a backward way of dealing with things — that we would just choose to absolutely destroy these families and then try to put them back together,” she said. “It didn't work.”

The three FIRST Clinic lawyers, who are partners at the ABC Law Group, began their work with low-income clients after seeing the effectiveness of early intervention with parents who could afford a private attorney when faced with CPS allegations. Many of those clients also struggle with addiction. But their relative wealth enables them to marshal more resources, such as hiring caregivers to supervise and assist with child-Frearing.

“The outcomes are drastically different than when a parent is unrepresented,” attorney Ballout said. “A vast, vast majority of the clients that privately retained us, they never had a removal, and they never had a filing.”

Ballout and his colleagues were also angry about Department of Children, Youth and Families practices and the court process. In case after case, they said, the department had failed to provide timely and meaningful assistance to parents of newborns — despite the legal requirement to make “reasonable efforts” to avoid foster care separation. Their frustration also extends to judges, who they said rarely hold the department accountable for meeting that standard.

The department disputes the lawyers’ assessment that “reasonable efforts” fall short in Washington state.

In a statement, spokesperson Gutierrez said: “If a parent of a substance-exposed infant is willing and able to work with DCYF, we offer voluntary services, encourage and support community connections to complement that support, including various community programs and connections to treatment providers where parents can attend with their infant, and other in-home services offered through voluntary services.”

That said, early evidence suggests that the FIRST Clinic model, which so far has served nearly 400 clients, helps keep families together. Between July 2019 and November 2021, out of 72 cases with a recorded outcome, 89% of babies remained with their parents or other relatives.

During the pandemic, calls to CPS, and thus dependency filings, have fallen dramatically. But court data shows that between 2018 and 2020, the number of filings involving babies less than a month old dropped 34% in Snohomish County, where the clinic serves the most clients, compared with 15% statewide.

“While we do not know for certain, we cannot think of another factor in Snohomish County that would reduce filings for this age group other than FIRST,” AyAy said.

Justice keeps her baby

When Justice found out she was pregnant with Mason, she and the child’s father were living in an RV. She knew that getting clean was just the first step to keeping her baby. She would also have to show the social worker that she had adequate housing.

As Justice was leaving a Seattle treatment program for pregnant women two years ago, a counselor there handed her Ballout’s number, and he connected her with the FIRST Clinic’s parent ally, Gina Wassemiller. Within a day of their first conversation, Wassemiller helped the couple get a room at the Holiday Inn in Everett.

Wassemiller understood what they faced. Two of her own children had been placed with relatives because of her substance abuse, and she had later entered treatment and a voluntary agreement with the department to avoid having her third child removed.

With Wassemiller by her side, “the help just didn't stop,” Justice said. “It was a phone call every day.”

Wassemiller also connected Justice with other local resources, including a housing navigator who got her on a waiting list for subsidized housing. “They were not going to give up until we were housed,” Justice said, “and they were not going to let us go back to the streets with our baby.”

Having a plan in place to provide safety and stability for Mason, along with the support to see it through, helped reassure CPS that the baby could be safe with his parents, Justice said. The FIRST Clinic, she said, “made DCYF feel like, if you want to join our plan, we can work you in, but we’re already on a path, and a good path.”

On Ballout’s advice, Justice agreed to accept Family Voluntary Services. The written agreement with the department allowed her to avoid the filing of a dependency petition to remove Mason. But she had to stay sober, arrange daily visits from family members, attend parenting classes and meet regularly with her social worker. The department’s involvement ended six months later, she said.

When Mason was 4 months old, he moved with his parents into a subsidized two-bedroom apartment in Everett, where they still live. Soon after their move, Justice became a full-time college student, and later interned with the FIRST Clinic, ABC Law and another law firm.

To be sure, not all FIRST Clinic clients are as successful as Justice has been. In roughly one of five cases, the Department of Children, Youth and Families still ends up filing a dependency against the parents. That’s more likely, Ballout said, if a client doesn’t have family in the area or can’t arrange around-the-clock supervision of mom and baby required by the department.

And parents in the program do relapse. Wassemiller acknowledged that she worries about some clients’ ability to safely care for their newborns. In those cases, she said, she brings in “extra eyes, extra places of accountability,” and finds opportunities to check in with those parents in person.

Not all parents learn about the FIRST Clinic before they give birth. The program’s lawyers get several calls a week from women who have just delivered and are desperate for help.

One afternoon last fall, attorney Neil Weiss rushed to the hospital to meet a woman recovering from a complicated childbirth. In just 15 minutes, he said he was able to come up with a plan for the mother and her baby: She would get mental health and drug and alcohol assessments, and the pair would live with an aunt and uncle and get help from other family members when they were released from the hospital. In the meantime, Wassemiller would start lining up other assistance.

“The social worker left feeling pretty decent about how things were looking for this mom,” Weiss said.

In Snohomish County, FIRST Clinic attorneys say they’ve seen a shift in child welfare workers’ attitudes since their program began. Before the clinic started, “the knee-jerk reaction was remove,” Ballout said of babies born exposed to drugs “Now it’s, ‘Let’s try to work with mom and baby.’ And they understand the harmful effects of removal.”

But elsewhere, particularly outside of the Puget Sound area, the lawyers often encounter more resistance to change, Ballout said. There are still counties where the possibility of keeping mom and baby together is rarely discussed. Instead, “the opening conversation is, ‘Where should this child be placed in foster care, and what is visitation going to look like?’ ”

The clinic's weekly support group is another opportunity for parents to get advice and encouragement. At a late January meeting held over Zoom, one of the half-dozen mothers present had given birth just two days earlier and joined from the hospital. Her baby had been born prematurely and was in the neonatal intensive care unit.

“I don't want you to go through this weekend alone,” Wassemiller told the new mom. “Call me no matter what time of day.”

Ivy Group introduced herself to the others and announced that she was 150 days clean. “I'm proud of you, Ivy!” one of the other mothers shouted.

Group, 23, learned about the FIRST Clinic while in treatment for heroin addiction last fall, giving her more than two months to work with the team before her son’s birth. With Wassemiller’s help, Group assembled a binder documenting each step of her treatment, the parenting classes she took and notes from her counselor and other supporters.

“The binder, the bio folder that they made with me, really sealed the deal with CPS,” Group said in a later interview. The department quickly ended its investigation, she said. “I’m going great, and that’s really thanks to FIRST Clinic, ’cause otherwise things could have gone a lot differently.”

Justice tells a similar story. Her son Mason is now 2, and she volunteers with two advisory committees at the Department of Children, Youth and Families. On June 17, she graduates with an associate’s degree in legal administration and already has a job lined up with the FIRST Clinic.

“I’m going to make changes,” Justice said. “And I’m going to be there for another parent who felt the same way I did — who didn’t want to work with the system, was scared, was hopeless.”

This story is being co-published with The Imprint, a nonprofit news outlet focused on the nation’s child welfare and youth justice systems.