This young woman, with her scuffed cowboy boots and her striking confidence, is plenty ambitious. Yet ask her about college and she is clear: “I don’t plan on it,” she said. What’s more, Beth Anderson, the college and career adviser with the Methow Valley district, is not pushing it.

Many high schools, said Anderson, “like to promote the fact that 100% or 95% are college-bound.” Such data points are not barometers of success, she argued, because they are more about “sending students off to the next institution” than helping them work through individual needs, skills and desires.

Are people ready to rethink what “success” looks like? And how to help students achieve it?

For teens across the country — many of them burnt out, confused or newly questioning long-held plans — that conversation is coming alive. It is unfolding amid scrutiny of the cost and value of a college degree and the multiplying options for alternative training.

The march to college is getting pandemic-adjusted. More students are taking gap years. Others feel they “don’t need college to be successful,” or don’t want to go until they know what to study, said Marguerite Ohrtman, director of school counseling and clinical training at the University of Minnesota. Some have lost ground academically. Others have earned certifications and want to use them. The pandemic has also driven some students to work more hours at jobs, earning money that remains critical to families.

“There are students who frankly are not ready to go to college and pay thousands of dollars” or take out hefty loans, said Ohrtman. Yet, she said, “there is still a push from school leaders that ‘we want 100% of our students to apply to college.’ ”

The situation has school counselors feeling stuck, said Mandy Savitz-Romer, a senior lecturer at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and expert in school counseling.

“We celebrate kids who get into college; we do not celebrate students who choose work,” said Savitz-Romer. She added that “we can’t just now pivot to choosing careers” without giving counselors time and support to have those conversations with students — a challenge compounded by caseloads that have counselors responsible for scores or even hundreds of students.

The college-for-all push, originally a response to criticism that counselors were the gatekeepers to college access, was embraced more than a decade ago as “a really easy standard to hold ourselves to.”

Now, it may be overshadowing the complex needs of teens.

“What happened is we jumped to this place of helping students apply to college and skipped over the entire exploration process — ‘What do I want to do? How do I want to contribute?’ ” Savitz-Romer said. “There is no process of discovery. It is, ‘Here, apply to college.’ ”

Students are pushing back. Early data from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center shows college enrollments down this fall for the second year in a row. Earlier this year, a survey of teens by the ECMC Group and VICE Media found that more than half believed they could be successful without a four-year college degree. (The ECMC Foundation, an affiliate of the ECMC Group, is among the many funders of The Hechinger Report.)

A report in October by the Center on Education and the Workforce at Georgetown University found that more education generally yields higher earnings — but not always.

The report shows that 37% of workers with a high school diploma have higher earnings than half of those with some college. What subjects people study, what fields they enter, even geography all matter in determining income, said Anthony Carnevale, director of the center and a co-author of the report.

A key, little-discussed factor, said Carnevale, is how well suited a person is to a job. “It is all about the match,” he said. “Where people are successful and have good earnings, it has to do with their own personal work interests and personality.”

That idea — finding what someone is good at and enjoys — is shaking up the adult labor market. (A record 4.4 million Americans quit their jobs in September.) The pandemic also shuffled students’ perspectives, said Jill Cook, executive director of the American School Counselor Association. Disruptions to school routines led students to more work and community experiences, she said, at the same time that they saw “reports about folks who have left their jobs” asking, “What is a good fit? What is bringing them joy and making them happy?”

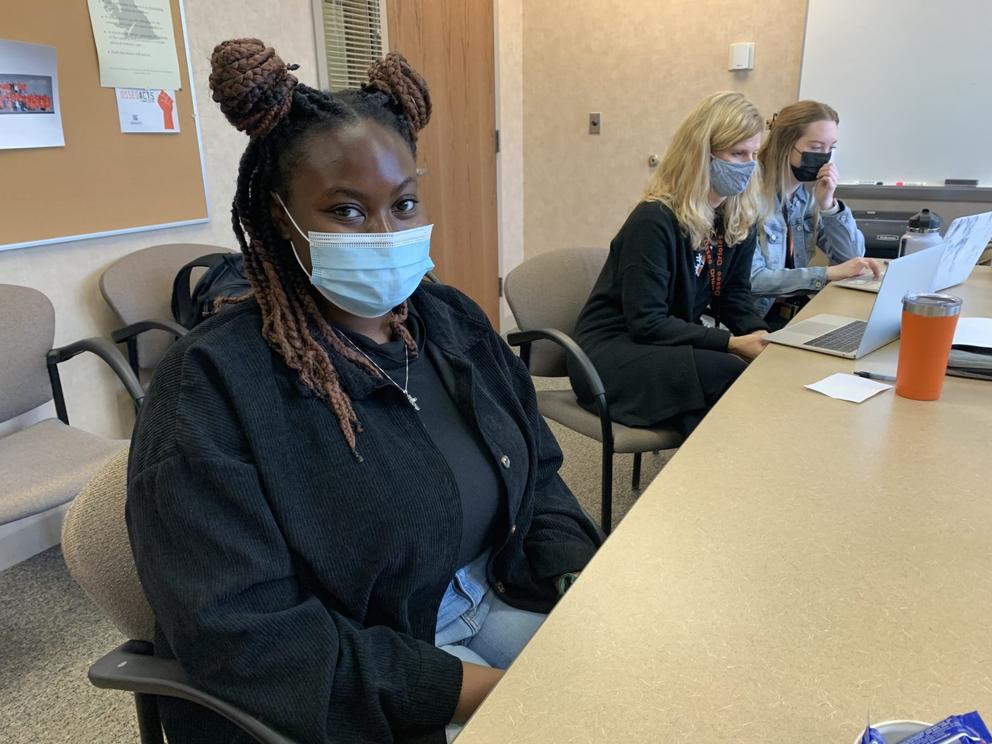

At Osseo Senior High School, which serves 2,100 students about 30 minutes northwest of Minneapolis, senior Dayo Onanuga joined several other students on a recent morning in a beige-wallpapered conference room and shared that she had long planned to be a surgeon.

But a year of online school changed that. “I was burnt out from the pandemic,” she said. Onanuga reasoned that if her energy was flagging now, “I probably cannot manage surgery” and years of training. Rather than give up the field — the pandemic highlighted for her “the injustices and struggles” faced by health care workers — she is now considering health care administration.

As it did for many students, the pandemic also forced Onanuga to manage her time and become more independent. She now also worries less about what others think of her choices or how she reaches her goals. “I kind of stopped caring about permission,” she said. “At the end of the day, nobody else is going to work this job until retirement but me. I should be happy. It can’t be something that I work two years, and then I hate it.”

Her classmate Kenji Lee had a similar revelation. Someone drawn to puzzles who has “math homework in my backpack all the time,” Lee planned to study engineering but admitted he “was just doing school to do school.” Then he got his driver’s license and discovered cars.

“Cars make me happy. Cars are fun,” he said. “I love working on cars, I like driving cars, anything to do with cars.” He now plans to attend a technical college to focus on engines for cars, boats or motorcycles. Adults tell Lee he won’t earn a lot, which makes him “double-check myself, ‘Do I really want to do this?’ ” But he concludes: “‘Yeah, I do.’”

While some high school students know what they want to do, many do not. Carnevale from Georgetown said the average age at which people “land in an occupation” — earning the median wage for workers of all ages — has risen from the mid-20s in the 1970s to the early 30s now.

“The journey is a lot longer,” he said. One reason, said Carnevale, is that the labor market now demands more specific skills. Students are especially anxious about spending to acquire skills they don’t end up using. Osseo senior Mila Phethdara said her mother earned a nursing degree, “realized she hated it,” then worked in insurance.

“My mom wants me to figure out what I want to do and stick with it. She doesn’t want to waste money,” said Phethdara, who is interested in the dental field. Still, she said, “I worry that I will switch out of it. That is an ongoing fear.”

It’s easy to see why many students feel pressure around education and career choices. A Georgetown report published in October showed that from 1980 to 2019, average college costs rose 169%, while earnings for those aged 22 to 27 rose only 19%. Some jobs don’t seem to justify the education costs.

Yusanat Tway, a sociology major at the University of Minnesota, wants to go to law school, then do human rights advocacy. “It will cost $200K” to get a law degree, she said. (The median salary for a lawyer is $126,930, but varies widely.) Tway, a first-generation college student, also has family financial expectations to think about: “Because my parents are immigrants, I am their retirement plan,” she said.

One big problem, said Carnevale, is a dearth of guidance to help students relate their interests, education and training to potential work. “There is a kind of missing link in this relationship between people and their work values, work interests, personality traits, then linking that to education and then linking that to training and then linking that to jobs,” he said.

In recent years, Career and Technical Education has been included in state graduation requirements and high school curricula in order to address this exact issue. It is far different from old vocational education (candlesticks in metal shop, anyone?) and can yield certifications, community work experiences and awareness. (What did you learn about client confidentiality in that health care course? What interested you?)

In Minnesota, the Greater Twin Cities United Way works with 17 school districts that have developed career pathways offering students of color and those with low incomes job exposure, college credits and training. The stated goal: jobs paying at least $25 an hour and zero college debt. Sareen Dunleavy Keenan, senior program officer of Career Academies, which connects schools and employers, said it takes coaching to change both how employers consider young talent — as in rewriting entry-level job descriptions and paying to train young people, not just older workers — and how students view “success.”

“Previously, it was ‘A four-year degree is a ticket out of here,’ ” she said. “Now we want people to stay in their communities.” She pitches “wealth creation,” which in this context means helping students forge pathways to high-wage local jobs (with “an upward career trajectory”), while they use college credits in high school, Pell Grants and employer tuition programs to pay for education, rather than acquiring debt.

Keenan said the 10-year project (the United Way is halfway through it) challenges schools to focus less on college applications and instead help students build a career “where they don’t need two, three jobs or a side hustle.” And to do it through local relationships.

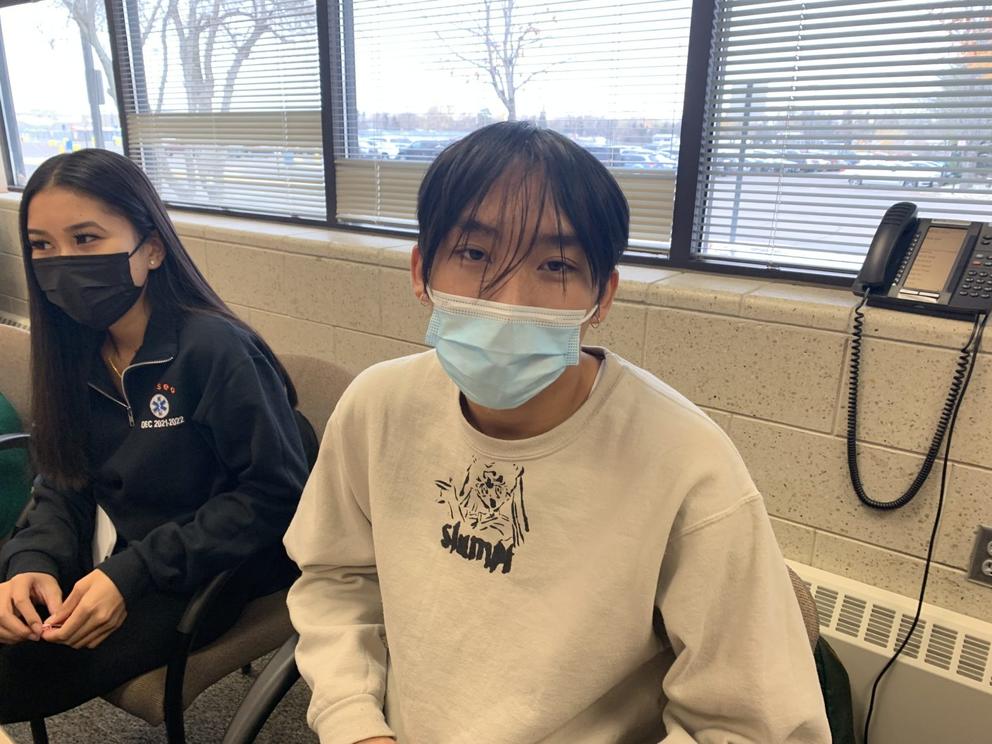

The approach may make sense. But the pandemic canceled many in-person experiences for students — and threw them off track. A school year “when you do almost nothing” was tough, said Hamza Mohammed, a senior at Humboldt High School in St. Paul, Minnesota.

He had planned to take calculus now but can’t because he didn’t feel comfortable taking precalculus online last year. Mohammed likes computer science, “but I haven’t shadowed anyone,” he said. “What I really need at this point is more career-based education.”

Hannah Chan, career pathways coordinator with the St. Paul district, sitting across from Mohammed in a Humboldt High conference room, was herself a first-generation college student and understands the setback of missing key exposures.

“I hear you loud and clear that because of COVID you couldn’t have these experiences,” she said to Mohammed. Many low-income first-generation students, she said, “only know the careers around them.”

The pandemic also surfaced issues of identity, community and social justice, which are especially keenly felt in Minneapolis, said Derek Francis, manager of counseling services at Minneapolis Public Schools. He said staff members had set up food drives in school parking lots as the pandemic hit. “We became community support, right off the bat,” he said of counselors. And, he asked, “What else has happened here?” referring to the murder of George Floyd.

Students are back, but the world has changed. As counselors, he said, “we want to make sure we are not missing out on college and career” planning. But, said Francis, “We have to talk about race and inclusion.” Many students, he said, “have been beaten up physically and emotionally” and now ask, “Why would I want to go to college?”

Francis spoke while at a school counselors’ gathering in a brewery outside Minneapolis, the in-person social piece of the Minnesota School Counselors Association’s virtual two-day conference. Counselors described students missing credits and falling behind academically, and talked about students feeling uncertain. “Our high fliers are still applying to college,” said one, but fewer “are feeling the pressure to apply soon.”

A counselor from South High School in Minneapolis said she had just written a letter of recommendation for a student who “is involved in, like, 50 organizations,” from social justice to climate change. The pandemic and social unrest have spurred activism and artistic and creative efforts, she said.

Education and work experts say it is too soon to tell if we are on the cusp of deep cultural change in how our education system guides students from school to work and life — wherever they come from.

Among the graduates of Osseo Senior High School’s Class of 2021, 20% went right to work, up from 11% just five years earlier. Jacqueline Trzynka, a school counselor, said that a few years ago the school began celebrating students once they declared a post-secondary plan — not necessarily college — with an orange T-shirt that read “I’M IN.”

This year, counselors are paying close attention to how they speak to students. Rather than focus on being “college ready,” they urge figuring out what interests students, then finding out how and where to pursue it.

“We are really conscious of not making it all about four-year [institutions] in our presentations, on our website, our materials,” she said. The aim is “to make students feel that whatever they choose is valued.”

In some places, expectations can be hard to unwind, said Edward Pickett III, a board director of the National Association for College Admission Counseling and a dean and college counselor at Polytechnic School, a private school in Pasadena, California.

“Success looks different for every person,” said Pickett, a former admissions counselor at Tufts University. Well-off parents at his school, he said, “have worked to have these resources, so they want to make sure they pass it along to their kids.”

To the parents, that often means having a child attend an elite school and pursue a high-paying profession. At the same time, the pandemic offered counselors “this opportunity to reflect” on the need “to present different opportunities” to students, said Pickett, himself a first-generation college student.

He sees more students planning gap years. Opal Hetherington, a senior at Polytechnic, hopes to spend next year on a farm. She is rethinking a previously scripted path in which “I was choosing to go to college because I am going to a college preparatory school and that is what we do,” she said.

She is still applying to college. But her onetime plans to major in political science now bend toward religion and thoughts of homesteading. Where she once “thought I was certain about things,” Hetherington said she now wants “to experience what happens to me.” She added, “I don’t want to always be living in a planning stage.”

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.