Child care in Washington state and in the U.S. is a broken economic system, according to providers and other experts. The pieces just don’t fit, despite small and large efforts to fix the problem.

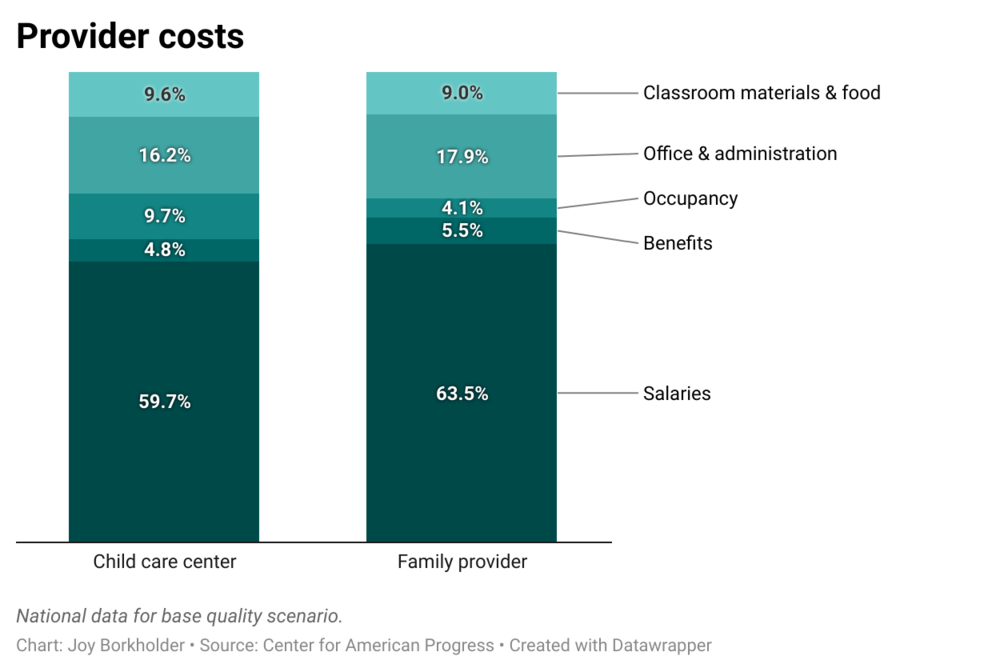

Even care that meets only minimum licensing standards is too expensive for many parents, yet child care providers cannot pay their workers a living wage. The providers cannot raise prices because if they do, they will lose customers. They cannot reduce their work force — which makes up 60% or more of their budget — because laws and the realities of caring for small children mean that they must keep ratios of workers to children low.

So the parents struggle, many child care workers do not make enough money to take care of their own families without government assistance, and providers scrape by or close their doors.

A lot of attention has been paid to the problem recently, in both Washington state and Washington, D.C., but many experts think the changes are still not enough. They look to places like Finland, where quality child care is heavily subsidized and generous paid parental leave is available. The results: high enrollment in preschool and strong educational outcomes.

InvestigateWest is a Seattle-based nonprofit newsroom producing journalism for the common good. Learn more and sign up to receive alerts about future stories at http://www.invw.org/newsletters/.

In contrast, states in the U.S. provide far less funding and face other constraints, forcing difficult trade-offs related to child care: “Do you give money to the single mom working, or the parent looking for training? Do you have lower-quality care for more children, or better quality for fewer children?” asked Gina Adams, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute, a nonprofit research organization.

Experts say that while the profit or loss margins are still razor-thin in the child care industry, there are things that can be done within the current system to help, like shared business services for child care providers, free or subsidized use of real estate and subsidized health insurance for child care workers.

Can the public and private sectors do enough to “reinvent” the current market, or will federal and state governments have to radically shift how and to what extent they fund child care?

Stacie Marez, director of ECEAP and community partnerships (Educational Service District 105), stands in the playground at Blossoms Early Learning Center in Yakima, Oct. 18, 2021. Blossoms is an ECEAP (Early Childhood Education and Assistance Program) preschool serving 3- and 4-year-old children in Yakima and is funded in part by Washington Department of Children, Youth, and Families. (Dan DeLong/InvestigateWest)

The costs of delivering care

The primary reason child care costs so much is that teacher-to-child ratios are kept low for infants and toddlers in order to provide safe, nurturing environments. In Washington state, those ratios are one care worker to four infants, one worker to seven toddlers, and one worker to 10 preschoolers. Thus, labor costs make up 60% to 80% of a child care provider’s budget, even though child care and preschool teachers here typically earn a little less than $16 per hour — below the median pay of fast-food cooks.

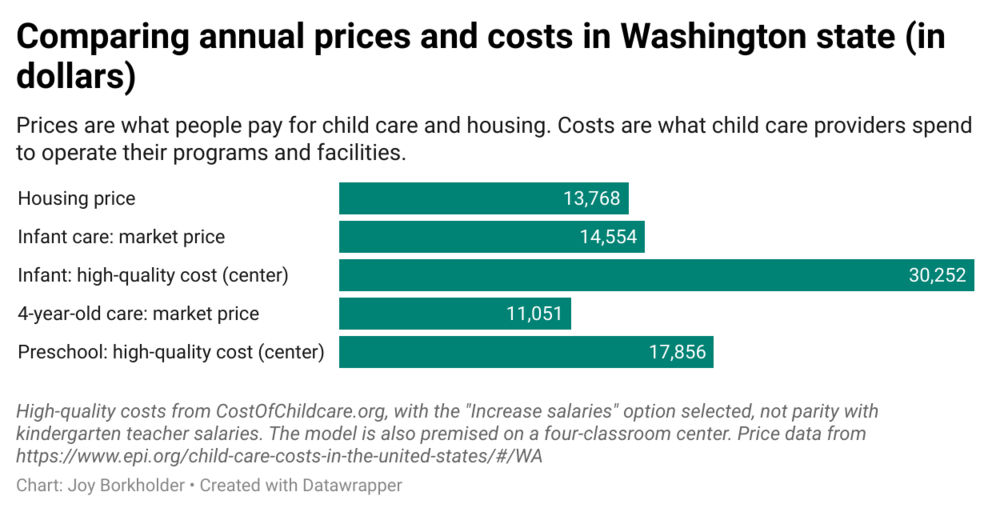

In Washington state, the prices families pay for care far exceed neighboring Idaho and Oregon. And the true costs to providers for high-quality, center-based care surpass the national average by several thousand dollars.

Louise Stoney is an independent consultant and co-founder of both the Alliance for Early Childhood Finance and the Opportunities Exchange, a nonprofit consulting group focused on early care and education. She argued that most people who are good at finance can run a large, high-quality preschool care program with decent wages. It’s the finances behind caring for infants and toddlers at a center that pose the greater challenge: “I don’t see how you do it for less than $25,000 per year,” she said — that is $25,000 per year, per child.

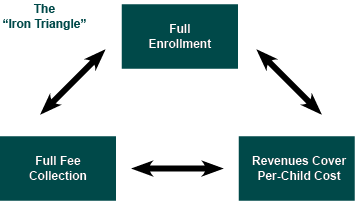

Stoney and her associate, Libbie Poppick, developed a concept they call the “iron triangle” of minimum prerequisites for early childhood education providers to turn a dependable profit: full enrollment, full fee collection and revenue that cover per-child cost (“accurate pricing”). For example, some providers still accept cash and checks from parents, instead of automatically billing their bank accounts, resulting in late and uncollectible payments that quickly add up in a business with such slim margins.

The iron triangle also assumes that providers can take advantage of technology, such as child care management software, or shared services to manage their businesses more efficiently.

Shared services alliances refer to providers that pool resources to share systems and people for accounting, human resources, regulatory compliance and other administrative work. In Oregon, child care providers are piloting a shared services alliance in several regions after promising results from a smaller pilot in two rural counties. Washington’s Fair Start for Kids Act, signed into law in May 2021, authorized creation of a “shared services business hub,” and recently awarded a grant for the pilot project.

Seattle already has a pilot program along those lines to help family providers participate in the city’s preschool program.

Stoney sees economies of scale and shared services as making room for higher teacher wages. “What shared services is really about is shifting dollars from administration into the classroom,” she said. “Providers have to either get bigger or network bigger. No one has ever pushed the field to do this. We’ve made administrative costs too high. And we don’t make efficiency a value.”

In the Seattle area, Sound Child Care Solutions is a nonprofit that shares administrative services and fundraising across eight separate child care centers that have common values and goals. Emily Adams, director of development and communications, said they see shared services as a way to enable center directors to focus on programming and invest more in supporting teachers to deliver high-quality care. Given the large number of immigrant and refugee families at some centers, those directors and teaching staff need extra time to incorporate different languages and cultures into their programming, as well as to receive training to address traumatic experiences within families. As a “value driven” organization, it also prioritizes equitable pay and comprehensive benefits for center directors and teaching staff, she said.

Some experts suggest that child care centers must have at least 100 full-time slots to make administrative overhead manageable, and that 300 slots are better. But most child care centers and school-age kid programs are small and thus unable to benefit from any economies of scale.

Family providers — that is, care based in a provider’s home — can care for infants and toddlers at lower costs, but Stoney said states need to stop regulating them as though they were tiny child care centers.

Guadalupe Magallan of Kennewick had been working 10-hour days taking care of kids in her home and then working evenings and weekends on administrative tasks. She recently hired an assistant to help with the office work.

“I can’t work all these hours with the children and still do all the administrative stuff to make sure I’m sticking to all the regulations and managing the paperwork, IRS, quarterly taxes, salary and more,” she said. Like Curry, she is currently losing money.

States are buying into the idea of helping providers buy and run software to assist with management needs. New Mexico recently partnered with Wonderschool to use its technology platform to assist child care providers, especially small centers and family providers.

Washington state providers told InvestigateWest about other ways in addition to looking at staff ratios and scale that governments could further assist them:

- To help with what one child care company executive called “astronomically unaffordable” real estate prices, cities or counties could designate some commercial locations as low-rent, highly subsidized properties for nonprofit child care providers.

- The state’s Early Learning Facilities program already offers grants or very low-interest loans to providers seeking to open or expand their facilities. These providers must serve low-income families that use state subsidies to pay for child care. In the next few years, about $40 million will be available, including money to help providers apply.

- The state could streamline its 90-day approval process for new child care sites, so that providers are not paying rent for several months before a center can open and begin making money.

- The state could create a shared risk pool for small providers to buy health insurance for their workers and workers’ families. A new program funded by the state will provide free health insurance for child care workers whose households earn less than 300% of the federal poverty level. But it will not cover all workers, nor any dependents.

And, finally, providers face the high costs of low-wage jobs in the form of worker training and turnover expenses. They want to figure out how to pay child care workers more, with wages and benefits that adequately value their work, in part so that workers will stay longer and providers won’t have to continuously train replacements.

State and federal support is already a key factor in the labyrinthine world of child care finance. Regional and state entities, such as Washington state’s Educational Service Districts. or ESDs, help deliver and add to federal aid for providers and parents. The service districts are public entities that “provide cooperative services” across public, tribal and some private schools offering K-12 education.

In south central Washington, for instance, ESD 105’s early learning program serves kids as a contractor for the federal Head Start program and for the Early Childhood Education and Assistance Program (ECEAP), which provide free preschool and supportive services for low-income families.

Stacie Marez, director of ECEAP and community partnerships at ESD 105, said the high rate of turnover resulting from low wages and lack of benefits means ECEAP programs at child care centers are constantly having to train new workers. When the three-year professional development cycle finishes, she said, “it’s just about the time we lose them to the school district.”

The school district can run state-funded ECEAP programs with better pay and benefits because of the district’s diversified funding sources, centralized administration (like shared services) and absorption of some ECEAP programs’ expenses, such as utilities and classroom space.

The prices we pay for care

Child care providers bill what they think community families can pay, not what it costs to run a financially stable business. But those “private pay” rates, also known as market rates, aren’t always high enough to keep providers in business.

The state sets Working Connections Child Care subsidy rates based on surveys that show what providers are charging in a particular area of the state. Working Connections is a program for low-income families with children up to 12 years old. The process to set rates for ECEAP-funded slots is more complicated.

Families eligible for subsidies find a participating provider to accept their children. The state then pays the provider. With ECEAP, parents pay nothing; with Working Connections, parents pay a share of that rate as a copayment, from zero to $215 per month, depending on their income.

Even if the subsidy rates were 100% of market rate, they would underpay many providers. The Fair Start for Kids Act just increased Working Connections subsidies from 65% to 85% of market rate and raised ECEAP rates by 10%.

That should help. But as Joel Ryan, executive director of the Washington State Association of Head Start and ECEAP, said, “Maybe we can get the subsidy rate high enough that it’s not terrible, but it doesn’t offset the real costs of child care.” Many providers will still face a loss from the state’s rates, and most families will continue to pay full price.

Mary Curry estimated that, for this past spring, her costs per child per month were about $1,200, but the state subsidy rate was about $750 to $800. Curry had been making it work, in part, by reluctantly keeping staff expenses low, as so many providers do. “Funding was so low, but I could make it work because my children were grown and I didn’t have to support them at home anymore,” she said. “My husband is the one who gives me this opportunity to do this, because he carries the overhead.”

The city of Seattle is planning a cost-of-quality-care study, as is Washington state. The state’s report isn’t due until November 2022. The text of the Fair Start for Kids Act says the Legislature’s intent is to increase subsidy rates gradually, until they cover the full cost of high-quality care. Only a few states are doing this.

According to a model developed by the Center for American Progress, a policy institute that supports “progressive ideas,” the Washington subsidy rate covers just 45% to 71% of “high quality” care costs, depending on the age of the child and the type of facility. The calculator estimates that in Washington the average annual per-child cost for “base” quality care (that is, care that meets minimum state regulations) in a family child care settingis $13,800. Investments to improve quality more than double that number, to $33,700.

Much of this increased cost goes to salaries and benefits for child care workers, whose training, planning time and retention rate are critical components of high-quality care. A few years ago, the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment found that 39% of child care workers in Washington relied on at least one public income support program, at a cost of nearly $35 million. Some refer to this as the high public cost of low-wage jobs.

The road ahead

The pandemic has made clear to some people that child care is a core part of keeping our entire economy running, akin to electricity and roads. At the federal level, Congress is considering multiple proposals that would infuse billions of dollars into the child care system. Yet, with one exception, that has always been a largely private system delivering a valuable public good.

During World War II, through the Lanham Act, Congress established subsidized child care services to support the families whose adult factory workers or members of the military were not able to care for kids. Family income did not factor into eligibility.

A substantial body of research indicates that a society’s investment in early childhood programs gives a strong return. In Boston, quality preschool led to higher rates of high school graduation and college attendance, as well as lower rates of juvenile incarceration. But many payoffs from early learning investments are long term, while state budgets are hammered out every two years.

Governments can see one quick return on investment in the short term: from better-paid workers. “A high-quality child care system costs money, but a lot goes into the pockets of child care workers,” said Simon Workman, a national expert on child care finance and founder of the consulting firm Prenatal to Five Fiscal Strategies. “They spend it. It circles through the economy.”

And yet these programs are not adequately funded in this country, according to providers and policy experts. For now, many families, particularly those with young children, remain stuck.

To that end, the parent ambassador program offered by the Washington State Association of Head Start and ECEAP has trained about 300 parents to advocate, educate and organize for quality early learning for all children. The 2021 legislative session felt like an exceptionally big win for advocates like the association. But the goal of a well-funded, well-supported system is still a long way off. And advocates wonder if they can repeat that success.

Some local providers and policy experts are cautiously optimistic that the state and national debate could shift permanently, to valuing quality child care from birth to age 12 as an essential need for everyone. But for now, Gina Adams of the Urban Institute said, “We have a market system that does not support good quality. … Our public system only deals with a small part of the problem, with inadequate funding and inadequate public support.”

Do you work or have you recently worked at a child care center? Please call us at 1-425-954-7169 or email us at childcare@invw.org and tell us how to get in touch. We want to hear your story.

InvestigateWest is a Seattle-based nonprofit newsroom producing journalism for the common good. Learn more and sign up to receive alerts about future stories at http://www.invw.org/newsletters/.